From the League to the UN: ending Swiss isolationism

One hundred years ago, Switzerland was facing a profound decision whether to join the League of Nations. The historic popular vote in 1920, and those in 1986 and 2002 to join its successor, the United Nations, represented key reflections of the changing attitudes to Swiss neutrality and isolationism.

“At this solemn moment, it’s not possible to say how we feel right now: inexplicable emotion, gratitude and infinite recognition for the result of this major popular consultation,” gushed the editor of the Journal de Genève newspaper in its May 17, 1920 edition. The day before, in a nail-biting finish, the Swiss had voted to join the League of NationsExternal link with Geneva as its headquarters.

A vigorous national debate over the previous 12 months had generated huge interest, resulting in three-quarters of the population turning out to vote. That Sunday it became clear that a comfortable majority of voters (416,870 for / 323,719 againstExternal link) backed membership, but a cantonal majority was also required.

Listening to the cantonal results trickling in had been nerve-wracking.

“At around 6.30pm, nine and a half cantons were in favour and eight and a half against,” wrote the editor. “We were counting on Zurich and St Gallen for the result. But Zurich was unfavorable. What a worry.”

Bern came next (for), followed by St Gallen (against). “Everything seemed lost until the liberating vote – Graubünden (for),” the editor declared. A single canton had tipped the balanceExternal link. Overall, French and Italian-speaking regions largely backed joining the League, while German-speaking Switzerland was divided.

“It’s hard to say exactly what arguments swung it,” said UN archivist and League of Nations specialist Pierre-Etienne BourneufExternal link. “If Switzerland hadn’t won, the League’s headquarters would’ve gone to Brussels and the future would’ve been very different.”

In the wake of the devastating Great War, the Alpine nation was keen to forge a global mission for itself using its diplomatic and humanitarian expertise. Geneva, home to the Red CrossExternal link, had already been earmarked by the League as the ideal universal host city.

Compatible with Swiss neutrality?

The burning question ahead of the vote had been whether membership of the new international order was compatible with Swiss neutrality?

Opponents on the left had attacked the LeagueExternal link as a global capitalist project, while mistrustful conservative Catholics and others on the right said Switzerland risked abandoning centuries of neutrality and its sovereignty. For some Germanophiles, the League was a dangerous, barbaric alliance of the victors, said Bourneuf.

And they feared that if a state were under sanctions “it could bomb the seat of the League of Nations [Geneva] as a form of reprisal”, he added.

More

When League of Nations reporters put Geneva on the map

With the horrors of the First World War still fresh in people’s minds, Radicals, Christian-Democrats and agrarian circles, meanwhile, had urged the Swiss not to remain outside such a visionary intergovernmental peace organisation.

Ahead of the vote, the League’s backers had granted the Swiss a tailormade “differentiated neutrality” status, laying the groundwork for adhesion.

“Swiss neutrality evolved. This meant it joined the League by refusing to use armed force in the event of sanctions but accepting to apply political or economic sanctions. For Switzerland this was a revolution. That’s what made the referendum so difficult,” said Bourneuf.

For the first time in its modern history, the Swiss people decided to abandon centuries of political isolationism and join a supra-national organisation. Switzerland also became the first and only country to launch a popular vote to join the League, said the archivist, which would be repeated twice for its successor, the UN.

Problematic

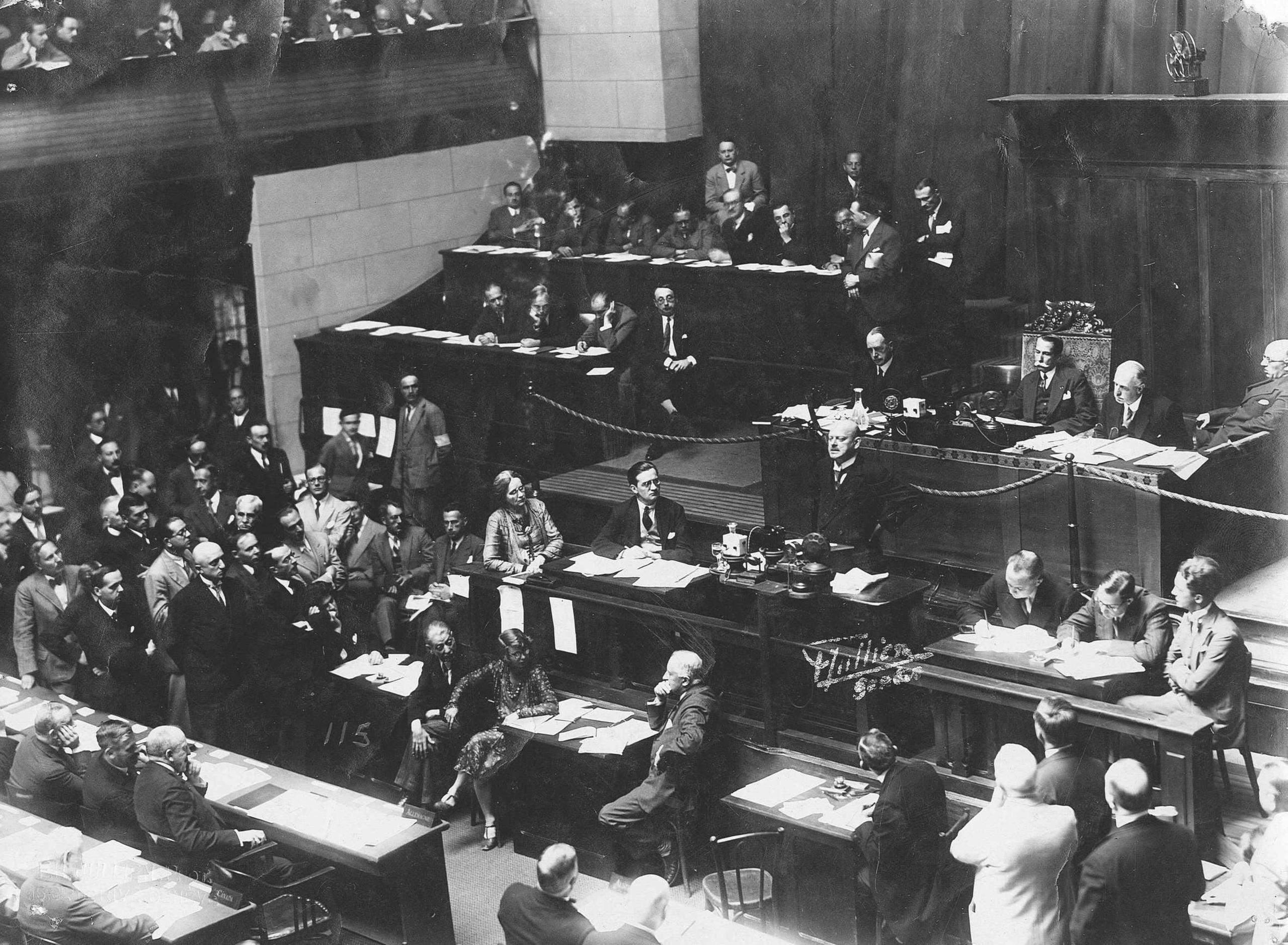

The League’s first Assembly External linkmeeting opened in Geneva on November 15, 1920 amid great popular enthusiasm. But from the organisation’s early beginnings, Swiss neutrality quickly became problematic. As the threat of war grew, in May 1938 the League’s council agreed to restore Switzerland’s full neutral status. A year later, with its neighbours at war, Switzerland cut ties with the League.

On June 26, 1945 when 51 countries signed the UN Charter in San Francisco, Switzerland was not one of them. The failure of the League had left a bitter taste, and it viewed the UN, as a kind of “winners’ club”.

Swiss neutrality was revived during the Cold War. But while other neutral countries slowly signed up to the UN – Switzerland resisted. In 1986, 75.7% of the population voted against such a stepExternal link.

Opponents repeated many of the arguments heard in 1920, namely, that if Switzerland became a UN member, it would have to abandon its sovereignty and neutrality. The global body also came in for heavy criticism.

“In Switzerland, the UN is seen as an undemocratic world and an expensive talk shop. A sort of anti-model,” wrote 24Heures editor Jean-Marie Vodoz after the vote.

Times were changing, however. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 contributed to the decline in importance of Swiss neutrality, whose meaning was shifting.

“Up until the end of the Cold War, the official policy of Switzerland was security through autonomy. Then there was a shift to security through international peace promotion, and after 2000 it changed to security through cooperation,” said Thomas FerstExternal link, deputy lecturer in military sociology and scientific project manager at the Military Academy (MILAC) at ETH Zurich.

Domestic debate on the UN was dominated by two opposing camps – those who supported opening up to the world by joining the UN and the European Union, and their nationalistic opponents on the right.

Supporters argued that Switzerland could no longer hide behind its neutrality and that it should abandon its closed policy for reasons of solidarity with the rest of the world and to better defend its interests. But those against feared that joining the UN would be costly, and compromise sovereignty, neutrality and national cohesion.

Despite resisting for over five decades, on March 3, 2002, the population voted to join the UN in a cliffhanger referendum. Like in 1920, a similar percentage were in favour (55%)External link and again it was decided by a narrow cantonal majority.

The mood towards Swiss neutrality and the country’s political isolation had changed: only 28% of voters said UN membership compromised its neutral status.

Since becoming the 190th UN member, Swiss attitudes towards membership and other UN-related issues have been largely positive and stable, as shown by the graph above.

“Switzerland has had some quite positive experiences with the international peace support missions in Kosovo (KFOR SWISSCOYExternal link), for example. At the same time there was 9/11, and a renaissance of neutrality,” said Ferst.

In the latest ETHZ Security 2019 surveyExternal link published in May, 59% of people supported Switzerland’s active participation in UN affairs. And 61% of those surveyed said they were in favour of Switzerland having a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

Timeline

1920: League of Nations founded in Geneva, with 58 members. 56.3% of male Swiss voters – women were not eligible – accepted the government’s proposal to join.

1929: First stone of the Palais des Nations HQ was laid; the new complex was completed in 1937.

1945: 51 countries signed the Charter of the United Nations in San Francisco.

1946: First UN General Assembly meeting in London. League of Nations officially disbanded.

1948: Switzerland gained observer status at the UN.

1986: 75.7% of Swiss rejected joining the UN.

2002: 54.6% vote in favour of joining the UN in a national ballot on March 3; Switzerland becomes the 190th UN member on September 10.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.