Capitulation before revolution

November 2018 will see the centenary of the 1918 General Strike, a political event that brought Switzerland to the brink of civil war. Here is a summary of the events.

Switzerland has always been part of Europe. This is nowhere as obvious as in the developments that led to the General Strike and had an effect on Swiss politics for decades to come.

November 1918 marks the culmination of political and societal developments and situations that had prevailed in Switzerland for many years. It was a combination of a world war, revolutionary coups in Europe, anxious and strict military leaders as well as a starving lower class.

Those living in the working quarters in Zurich and other Swiss cities in 1910 had plenty of things to worry about. It was common that several families had to share a flat, which was often old and damp. One wage per family was barely enough to survive on. The common concept of having one breadwinner did not work. Men and women were both forced to find a job.

More

Photos of workers were a labour of love

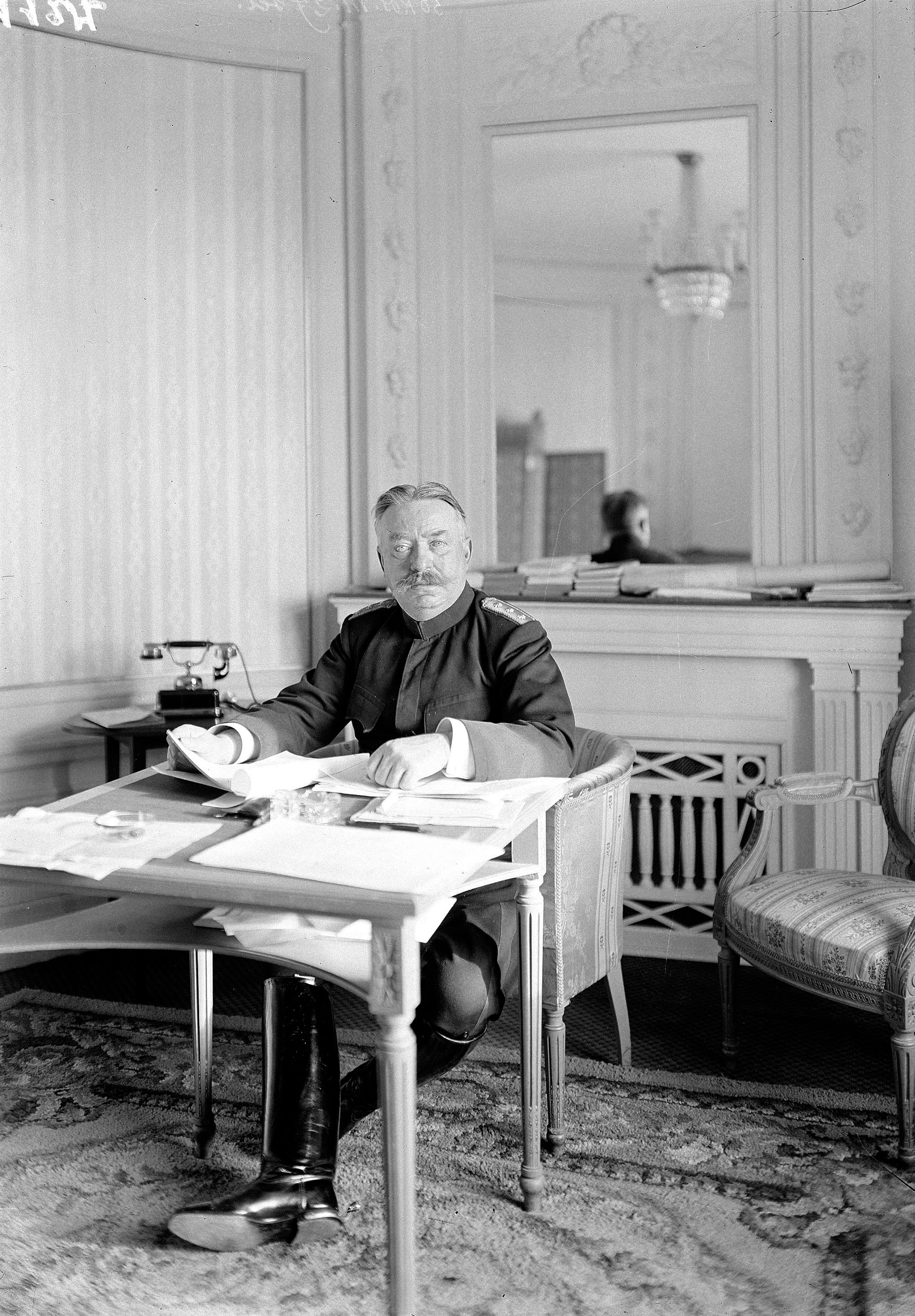

Suddenly, wages were no longer paid. Soldiers were conscripted for active military service: 238,000 militia men were mobilised under General Ulrich Wille’s command to defend Swiss borders against the warring parties, if needed. Many of these soldiers came from the working class. Their conscription posed big problems to their families given that soldiers did not receive a salary; Switzerland only introduced that during the Second World War. There were no social benefits either.

Resenting profiteers

This led to many families suffering from a huge loss in wages. Some household incomes halved, while other middle-class families benefited from the situation. Many Swiss entrepreneurs made enormous sums of money by supplying the warring parties with ammunition and other necessary materiel, which led to ridiculously high dividends for some Swiss shareholders.

The rift between rich and poor widened quickly and drastically. “You have to realise that the gap between those who had a lot and those who had nothing or very little grew massively between the working class and the profiteers, namely the entrepreneurs,” says Brigitte Studer, professor of Swiss history at the University of Bern.

More

A worker remembers

This resentment was growing, and so did the people’s need for their daily bread. Food was not only gradually rationed as of March 1917, it also became more expensive, which was a big problem for many lower-class families.

“In those days, an average wage earner had to spend half of his salary on food,” says historian Sébastian Guex from the University of Lausanne.

Some towns tried to alleviate the suffering by distributing food to the poor or selling potatoes at a cheaper price. However, the combination of the war, bad weather and poor harvests led to several hunger crises in 1916 and 1917.

The First World War had also influenced the various political camps. Here, the middle-class and military elite, there, a split left. In 1915, leading representatives of European socialist parties met in Zimmerwald, a small farming village near Bern. They discussed how legitimate it would be for the socialists and social democrats to support the warring governments.

Centrists between revolution and reform

The meeting in Zimmerwald was organised by parliamentarian Robert Grimm, who was to become one of the leading figures in the General Strike. The former book printer was part of the so-called Marxist centrists, who clearly embraced socialism but saw themselves as intermediaries between revolutionaries and reformists.

Lenin was also part of the group, and even though Grimm was opposed to his idea of staging a violent coup, he helped Lenin organise his infamous train ride from Zurich to Petrograd.

Among the left, the discord of the different trends often led to disputes about the power of interpretation of the movement.

The fuse for the 1918 General Strike started burning pretty early. On November 17, 1917, riots broke out in Zurich. A group supporting pacifist and conscientious objector Max Dätwyler gathered to demonstrate against the two ammunition companies in Zurich city. They were joined by younger radical forces. The “November riots” escalated with four people being killed and more than 30 injured.

Spiral of unrest in Switzerland

In 1918, Switzerland did not get a break. In February, leading social democrats and trade unionists founded the “Olten Committee”, which was the response to the government’s plans to introduce obligatory civilian service. Grimm was one of the committee’s spokespeople.

Protests against food shortages swept across the country. The Ticino region was suffering particularly badly. In March, workers looted the central dairy in Bellinzona.

On May 1, the government announced a hike in milk prices. Two weeks later, cheese was rationed. But while farmers made a profit, workers in the cities did not. Swiss cheese factories no longer made cheese from skimmed milk, they produced casein instead, which they sold as a rubber substitute to German arms manufacturers.

In the years leading up to the General Strike, women in particular protested during “market unrests” in towns such as Biel, Thun and Grenchen. In June 1918, about 1,000 women gathered in front of the town hall. They demanded a stop to the price hikes, the introduction of a poverty line and food redistribution. A few days later, around 15,000 people showed up for the second rally.

The female protestors submitted the first-ever cantonal petition. Marxist Rosa Bloch-Bollag from Zurich was the leader and political mastermind of the movement. She was also a member of the Olten Committee.

From the banks to the street

In September, bank employees went on strike demanding a minimum wage. It was unprecedented that bank clerks were active in the trade unions, not to mention lay down their tools.

This new development worried large circles of the Swiss middle class as well as the military and fuelled the fear of a revolution. People were anxious that a Russian-style coup could happen in Switzerland.

The attitude of the Swiss military leaders did not necessarily have a de-escalating effect. Most of them blamed the labour movement for undermining society.

“The army top brass and the government were living in a filter bubble, as we would call it today,” explains historian Jakob Tanner. “The fact that the labour movement made a real effort to find realistic ways to enforce their interests was completely ignored. It was all about the military gaining importance again in the future.”

How to stop a wildfire?

General Ulrich Wille represented a Prussian view of the military: above all, a good citizen is a soldier. He responded to the hesitant behaviour of the cantonal authorities and the Swiss government with a forceful demonstration of power. The protests, he thought, should be nipped in the bud: what happened in Russia and Germany, where the existing governments had been put out of action, must under no circumstances happen in Switzerland.

It’s obvious today that the Swiss labour movement was not equipped to face an armed uprising, and the majority was clearly against it. The events in the neighbouring countries, however, make the military’s worry somewhat understandable.

More

‘I think they’re planning a civil war’

Thus, cavalry and infantry from rural regions were moved to the cities of Zurich and Bern. This, however, did not calm down the protests. On the contrary, the situation escalated in November. In response to the announced protests, military flyers were handed out threatening the use of machine guns and hand grenades.

On November 9, workers laid down their tools in 19 cities and towns. The following day, violent clashes broke out in Zurich. For fear of losing its influence over the labour movement, the Olten Committee quickly drafted a list of demands. Many had been under discussion for a long time, such as proportional representation, women’s suffrage, pension and invalidity insurance, a 48-hour working week. On November 12, the Committee, somewhat unprepared, called the nationwide General Strike.

More

‘The troops sparked an escalation’

Finally, on November 12, 250,000 workers laid down their work across the nation. In most places, the strike went on in a peaceful and orderly manner. For safety reasons, labour organisations had gone as far as banning alcohol in some parts of the country.

The term “general strike” does not really paint an accurate picture though. It was not a single event that was coordinated all over Switzerland. People were injured where the military got involved. In Grenchen, three people were killed in a clash between strikers and military troops.

Capitulation and prison sentences

The government stood firm and placed federal staff under military jurisdiction. White-collar employees, students and newly formed vigilante groups kept the most important companies going. On November 14, the Olten Committee was brought to its knees and the strike was called off. Several groups kept on striking for a few more days, but then it was over.

The General Strike did not happen without consequences for the left. In spring, a military court acted quickly and initiated legal proceedings against 35,000 strikers. Grimm and some of his committee friends were given a prison sentence. Many railway workers, the backbone of the industrial action, lost their jobs or were disadvantaged in one way or another.

In the short term, the capitulation seemed to be a fiasco for the labour movement. However, many of the Olten Committee’s demands became reality in the years to come. The 48-hour working week was introduced in 1919. Later achievements such as old-age and surviving dependents insurance as well as voting rights for women can also be attributed, indirectly, to the General Strike.

The events of 1918 are also the basis of the consensus-oriented system of social partnership between employees and employers. There were plenty of issues they did not see eye to eye on, but they all agreed that having got a glimpse of the abyss of civil war, nobody wanted it.

More

How propaganda flooded Switzerland during WWI

Translated from German by Billi Bierling

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.