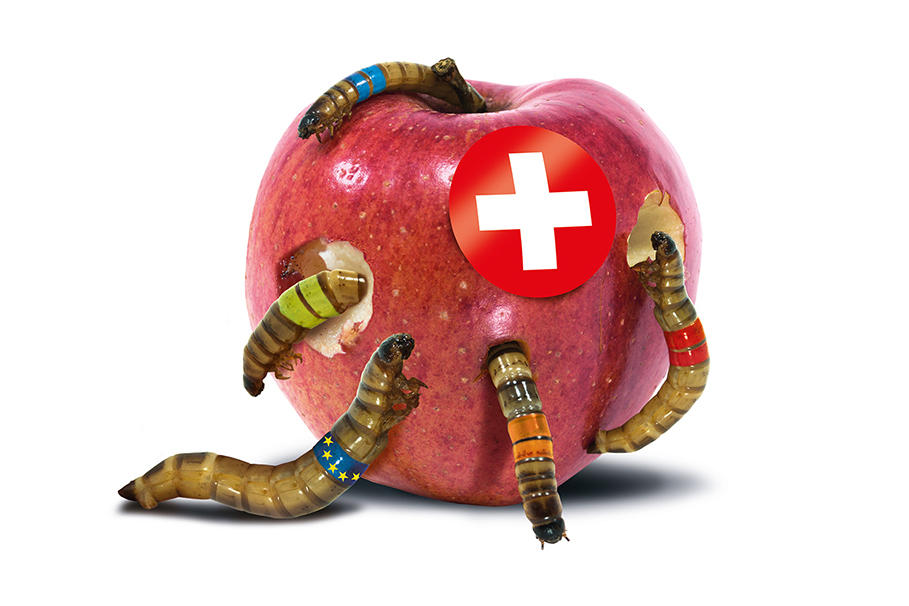

Campaign funding still a taboo topic in Switzerland

Campaigning for the upcoming Swiss parliamentary elections is in full swing. However, it's unclear exactly who funds the parties and candidates on the ballot. Here’s what we do know.

We asked the seven main Swiss political groups this question. Those with the greatest representation in parliament (the Social Democratic Party, Radical Liberal Party and Christian Democratic Party) are also investing the largest amounts.

The country’s leading party, right-wing Swiss People’s Party, was again not willing to reveal its campaign budget. Like in years past, it undoubtedly has a sizeable war chest, enabling it to cover the country with its controversial posters and send costly mailshots to all households.

- Swiss People’s Party (right-wing): no information

- Social Democratic Party (left-wing): CHF1.4 million ($1.4 million), same budget as in 2015

- Radical Liberal Party (centre-right): CHF3 to 3.5 million, approximately the same budget as in 2015

- Christian Democratic Party (centre): CHF2 million, same budget as in 2015

- Greens (left-wing): CHF180,000 francs, up from 2015

- Liberal Green Party (centre): CHF600,000, up from 2015

- Conservative Democratic Party (centre-right): CHF600-700,000, up slightly from 2015

In total, the national parties are thus forking out nearly CHF8 million for campaigning. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg. To this must be added the expenses of the parties’ cantonal sections. These amount to at least CHF17 million, according to a survey by Swiss public radio and television, RTS, which obtained replies from over 80% of the parties’ cantonal sections.

The personal expenditure of the candidates is the most difficult to survey, yet it also weighs most heavily on the overall campaign budget. In the 2015 elections, candidates spent an average of CHF7,500 each on their personal campaigns, according to a study by the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS)External link.

The reason is that private donors are increasingly supporting specific candidates, in the hope of gaining greater leverage on political decisions. “Those contributing do not do so to stimulate debate. They have one objective: to influence politics,” says Georg Lutz, a political scientist at the University of Lausanne.

Given the record number of candidates – over 4,000 – the total amount of money poured into personal campaigns this year is likely to exceed CHF30 million. All in all, if the trend observed since 2003 continues, campaign expenses this year should easily surpass the CHF50 million mark.

According to Lutz, “For the parties, an expensive campaign is not necessarily synonymous with victory. What counts is having a compelling message and being present on the issues that concern people.”

For individual candidates, meanwhile, investing significant resources may pay off to ensure that their faces are visible on roadside signs or on potential voters’ Facebook newsfeeds.

“Above all, candidates need to make themselves known; the message they convey is secondary,” says Lutz.

Their goal is to gain the highest number of individual votes and climb to the top of the electoral list. This need for visibility is particularly effective for first-time candidates who do not have the same media exposure as their outgoing colleagues.

The large rightwing parties, which are closest to the business community and generally receive most support, tend to downplay its importance. “Obviously, it is a significant factor. But the personal touch is just as important,” says Andrea Sommer, head of communications for the Swiss People’s Party.

The centre-right is more or less of the same opinion. “In a campaign, getting as close as possible to voters is key. This does not require huge financial resources, but constant commitment by the candidates and activists,” says Fanny Noghero, spokeswoman for the Radical Liberal Party.

Parties on the political left, meanwhile, highlight the inequality that results from the lack of transparency in campaign financing.

“Unfortunately, money carries considerable weight, since public visibility is bought at a high price by certain parties,” says Regula Tschanz, secretary-general of the Greens. “Being able to cover Switzerland with posters or send mailshots to all households obviously plays a role in an election campaign,” adds Gaël Bourgeois, spokesman for the Social Democratic Party.

At present, Swiss law does not contain any provisions governing the financing of political parties. Of the 47 member States of the Council of EuropeExternal link, Switzerland is the only one that has not drafted a law on the subject, for which it is regularly criticised by the Group of States against Corruption, GRECO. Five cantons – Fribourg, Geneva, Neuchâtel, Schwyz and Ticino – have nonetheless adopted rules on party financing and political campaigns.

For nearly half a century, the Swiss parliament’s rightwing majority has systematically rejected proposals by the left aimed at establishing a minimum level of transparency. This lack of a legal framework has, paradoxically, prompted the business community to take steps towards greater transparency in recent years.

The country’s three largest banks, UBS, Credit Suisse and Raiffeisen, the food giant Nestlé, the insurer AXA Winterthur and the airline Swiss make their donations to political parties public.

A majority in both the parliament and cabinet considers the transparency requirements to be incompatible with direct democracy. “The system works well. To survive, it must continue to depend on the political and financial commitment of citizens and businesses,” says Noghero of the Radical Liberal Party.

In the opinion of the Swiss People’s Party, all citizens and businesses must be able to decide freely how much money they wish to give to a party or organisation. Enhanced transparency rules would infringe on the donors’ right to confidentiality and privacy, according to the country’s largest party.

The Christian Democratic Party, meanwhile, regrets that the call for transparency targets only political parties, “whereas the direct influence of associations, trade unions and NGOs is just as important.”

All these arguments do not convince the political scientist Lutz, however. “Small donations must certainly be protected from the public eye, but it is not acceptable that today Facebook or Russia can in theory fund an electoral campaign in Switzerland perfectly legally and with full confidentiality.”

He believes this resistance stems mainly from the rightwing parties’ fear of losing the contributions of certain major donors who do not wish to be publicly associated with a particular political movement.

As in the case of banking secrecy, the intransigence of the Swiss political right may not be able to withstand the current groundswell sweeping through politics, and society as a whole: the call for transparency.

In October 2017, the leftwing and smaller centrist parties tabled a popular initiative entitled “For more transparency in the financing of political life“.

The text, which could be submitted to voters next year, calls on political parties to publicly disclose the origin of donations above CHF10,000 and their campaign expenses for elections and referenda when they exceed CHF100,000. A counter-project to the initiative was drawn up by a Senate committee: it sets the bar for the amounts subject to transparency at CHF25,000 and 250,000 respectively.

“I am optimistic. All these initiatives are heading in the right direction. In several cantons, the public has clearly indicated its support for more transparency in the funding of political parties,” the executive secretary of GRECO, Gianluca Esposito, told swissinfo.ch recently.

Contact the author of this article on Twitter: @samueljabergExternal link

Translated from French: Julia Bassam

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.