2024 represents ‘critical juncture’ for future of democracy

India, Indonesia, Pakistan and the United States – these are just a few of the many countries holding elections in 2024, the “biggest election year in history”. Daniele Caramani, professor of comparative politics at the University of Zurich, explains why citizens should be especially vigilant this year to ensure democracy is not weakened.

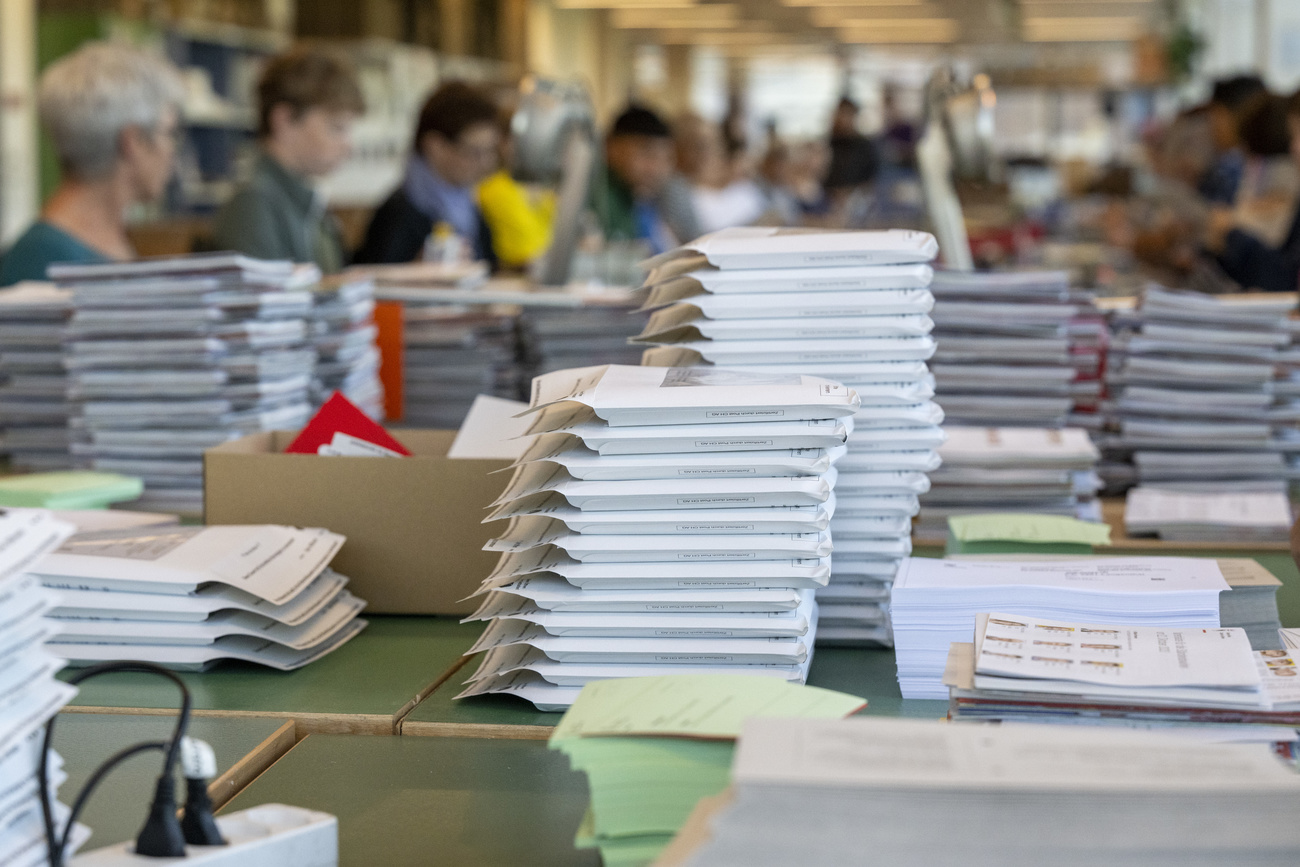

This year over four billion people are expected to go to the polls in 80 countries – that is more than twice as many people who voted last year.

The elections range from countries like India, home to 1.42 billion people, to tiny North Macedonia’s presidential election. The EconomistExternal link has called 2024 “the biggest election year in history”.

But many elections will not be totally free and fair: Russia is also voting, and it already seems fairly clear that President Vladimir Putin will enjoy another term in office.

More

Save the dates: a ‘year of democracy’

SWI swissinfo.ch: Half of the world’s population goes to the polls this year. What are the risks?

Daniele Caramani: There is a risk that dangerous fluctuations may increase. Each election features parties and leaders who have proven they want to undermine democracy. This election year is not just about ideological positions and political measures but also about the development of democracy.

You have to be blind not to see this. 2024 will be a year when democracy could be weakened to an extent that threatens its survival. Given the magnitude of these elections, we should all be very vigilant. The past has shown that there are “waves” that sweep around the world, such as just after the First World War, when there were fascist and communist attacks on liberal democracy.

I very much fear that we are once again at one of those critical junctures where every action and every decision matters.

SWI: What interactions and connections do you see between the different national campaigns and elections taking place in various parts of the world?

D.C.: Elections reflect the different levels at which we live our lives. In some ways, the issues in this huge election year – climate change, migration, war, artificial intelligence and the survival of democracy – are global. We read about these issues and understand that global action is needed.

But at the same time, elections remain a national or even local matter. We elect the candidates in our constituencies. They run the election campaign at the local level, and in some rural areas some voters have a disproportionate influence.

In this sense, democracy has remained a “pre-globalised” form of governance that no longer seems able to do justice to the scale of the problems for which citizens expect solutions. Individual countries appear powerless to deal with these problems.

SWI: How can democracies address this issue?

D.C.: International coordination is difficult. Most coordination takes place in international organisations that are not directly elected. This makes cross-border cooperation easier. But the impression remains that international organisations have little connection to citizens and are far removed from their everyday problems. It’s a difficult balance, and many people are unhappy because of it. But we shouldn’t just throw everything overboard. Solutions can be found by examining possible improvements.

SWI: Why should an individual citizen who can only vote in one particular country care about elections in other parts of the world?

D.C.: We live in a highly connected world. This means that what happens in one country can have an impact on many other countries, especially in Europe, where the most important decisions are made at the European Union level.

What’s more, countries are increasingly influencing each other in very clear ways. I’m thinking, for example, of the influence of some US ideologues on populist right-wing extremist parties in Europe but also illegal attempts by hackers sponsored by authoritarian governments to influence the public. Migration also connects voters across national borders.

Many migrants keep the right to vote in their countries of origin, and parties sometimes organise campaigns abroad to mobilise those who have emigrated. All of this connects elections between different countries in an unprecedented way.

More

A global stress test for freedom of expression

SWI: Switzerland is a well-established democracy that sometimes inspires other states via its referendums. Does it also offer inspiration for its elections?

D.C.: Yes, in principle. Switzerland is seen globally as a wealthy, peaceful and efficient country. However, its political model is often misunderstood. The relationship between direct and indirect democracy is complex and difficult to understand from the outside. This also applies to the consensus principle based on compromise.

International reporting about Switzerland often focuses on the anti-immigrant and anti-European referendums with xenophobic undertones. This is unfortunate because it reduces its rich political system to something simple and superficial.

SWI: You have already pointed out the dangers and risks. But what are the positive effects of the ‘biggest election year in history’?

D.C.: Elections are moments when many things become possible. My hope, of course, is that they provide an opportunity to strengthen democracy. But opportunities are created through actions and decisions. They don’t just come from nowhere.

Each decision this year will determine whether an election can strengthen democracy or not. The candidates, the campaigns, the tone of the debates and the honesty of the arguments also play a role. It’s about decisions made by leading politicians, but also decisions by individual citizens. We all have to take responsibility for our decisions.

The world is facing a crucial year for the future of democracy. But I am not fatalistic. Opportunities arise through action. Strengthening democracy is possible. We are not condemned to weakening it by “fate” that cannot be changed.

SWI: What does it take to better protect democratic practices and human rights?

D.C.: There needs to be an understanding that democracy, the rule of law and the protection of our rights as free citizens are not just the task of elites, but of everyone. It’s important to recognise that this task requires effort and time.

Being a citizen is demanding. We must be informed and able to compare different positions, and we must discuss openly and tolerantly based on facts and complex issues. Citizens must participate based on informed debate and information. This is what makes democracies strong.

Anger and gut feelings have their place, but only insofar as they do not replace civil and rational debate based on facts. This is even more important when party leaders undermine institutions, when money plays too big a role in election campaigns and when courts and the media are politicised. Those who vote are required to have the ability to criticise. Nowadays, too many people blindly believe the lies told by manipulative politicians.

SWI: What are you most looking forward to this election year?

D.C.: Elections and votes are always wonderful moments when citizens’ right to have a political voice is celebrated. If this happens on such a scale as in 2024, that gives hope. The right to replace leaders and vote on proposals has only existed recently in history. We shouldn’t forget that. It is a rare privilege that we have as a current generation, and one that was only truly introduced globally after the Second World War.

The generations before us fought and contributed to our incredible progress as humanity. No other political system is able to guarantee a similar level of freedom and prosperity as democracy. We must not allow this to be jeopardized.

Edited by Benjamin von Wyl. Translated from German by Simon Bradley.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.