When Switzerland clipped its army’s wings

Thirty years ago the Swiss voted on whether to abolish the army. Although the initiative failed, a surprisingly strong vote in favour led to reforms. Did the vote also cast out the Cold War mindset? We take a look back with the main protagonists at that time.

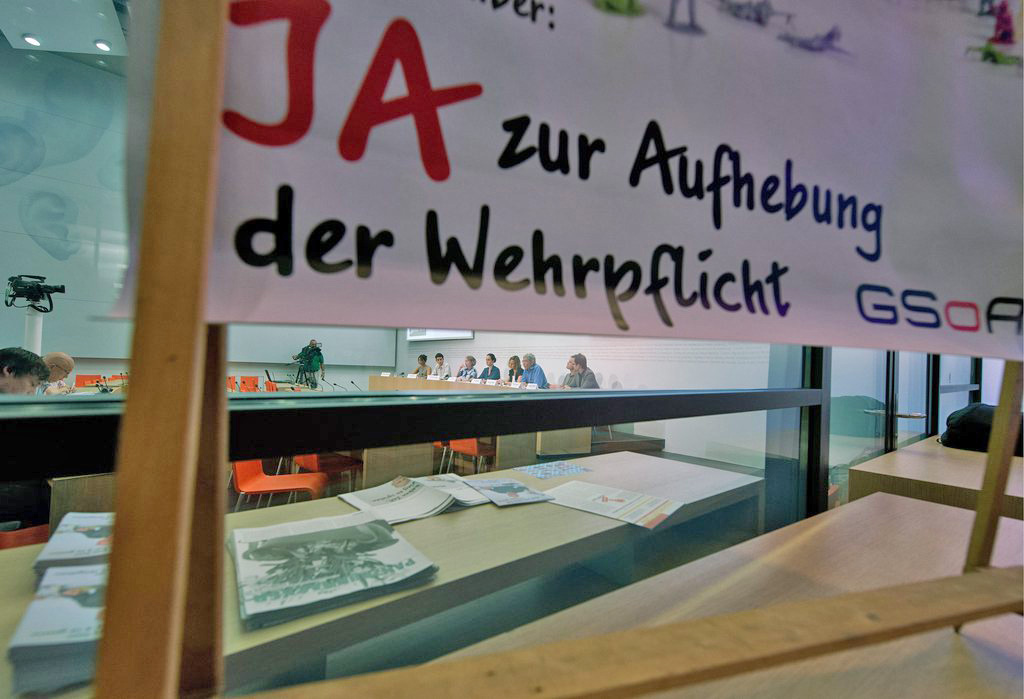

On November 26, 1989, three weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Swiss electorate voted on whether to abolish the army. The initiative had been organised by the Gruppe für eine Schweiz ohne ArmeeExternal link (Group for a Switzerland without an army), founded in 1982 and known by its initials, GSoA.

To universal amazement, more than a million people, or 35.6% of voters, backed its plan to abolish the army.

The activists who started it

“No, I didn’t expect that result,” says Oliver Krieg, a pensioner who was on the committee behind the initiative. With 100 members, the organising committee was one of the biggest on record. His job description was “petrol station attendant”.

Krieg worked night-shifts in a motorway service station in order to have time during the day for his activist work against nuclear power and in favour of communal living. Collecting signatures in favour of abolishing the army in the small towns of canton Solothurn wasn’t a big stretch for him.

“I could hardly annoy people more that I already did, with my long hair and hammer-and-sickle badges,” he says. The army was already a part of his biography: Krieg was a conscientious objector.

In those days, as they are now, Swiss men were required to do military service. But back then, the only alternative to military service was a prison sentence lasting between a few months and more than a year. Some who took that route were also banned from working.

“We conscientious objectors were advised to get a one-way ticket to Moscow,” recalls Marc Spescha, a Zurich lawyer and a co-founder of GSoA. About 10,000 men refused to do military service in the 20 years before the referendum. That was not many compared with the number of troops: neutral Switzerland’s army was vast at the end of the Cold War, with 600,000 members, or every fifth man in a country of 7,000,000.

‘How can you rehearse war?’

This militarised country angered women too. Renate Schoch, who today works for a labour union, powerfully describes how she thought it was scandalous that her partner had to serve in the military. In the first week of his cadet school, she transformed from an unpolitical person into a committed pacifist.

“When I realised what my boyfriend was going through, I was disgusted,” she says. “Why does anyone subject themselves to this? How can you rehearse war?”

That was in 1987. For Schoch, the first time she attended a GSoA meeting was a big step. Suddenly she was sitting at a table with people her father viewed as enemies – Trotskyites and left-wing Social Democrats – and she recognised that she shared some basic values with them.

After the referendum, Schoch worked for the GSoA for ten years. She also became engaged in local politics from time to time and is now a member of the management of Switzerland’s biggest labour union.

This political life began as a confrontation with a “sacred cow”. “It was a surprise encounter with politics,” she says.

The writer Max Frisch described the army as a “sacred cow” when he was campaigning for its abolition before the referendum. “It is taboo,” he said. “We can talk about God or his non-existence in polite society; we can speak indecently about sex in polite society. But we can’t talk about the army.”

One of the reasons behind Frisch’s observation lay in Switzerland’s neutrality. It is one of the most deeply ingrained aspects of the country’s identity and compels Switzerland, even today, to organise its defence independently – and therefore expensively.

‘A democracy must be able to tolerate that’

Andres Türler would become a colonel in the army’s general staff and a city councillor in Zurich. Thirty years ago, he was a liberal-minded lawyer campaigning against the GSoA initiative.

Today he says the result didn’t surprise him. He was equally unsurprised that a majority of soldiers voted for the abolition. “Military service isn’t voluntary and it isn’t fun. Even I entered the military because it’s an obligation.”

Anger about this obligation explains a part of the votes, he says. But Türler estimates that even in today’s Switzerland about a fifth of the population fundamentally questions the need for the army. A democracy has to tolerate this, he says.

Türler valued the debates sparked by the GSoA initiative. “The activists were not, in my view, traitors; rather they were fellow citizens with a different opinion. The discussions back then breathed life into our democracy.”

Among Türler’s opponents in panel debates was Spescha, whose memories of the campaign are similarly statesmanlike. “We always stressed that the best democracy is one where everything can be discussed and questioned – even the army.”

Trench-warfare rhetoric

From the political establishment, the army opponents encountered trench-warfare rhetoric.

“Switzerland doesn’t have an army, it is an army,” is how the government launched its campaign message against the initiative a year before the referendum. The initiative attacks the pride “of all the soldiers in our country,” said one Christian Democrat in the parliamentary debate.

A Swiss People’s Party parliamentarian declared at the speaker’s podium that he was gripped by “righteous rage” at this “treacherous initiative”. “It has really gone too far when extremist crackpots want to abolish our army,” he said.

Parliamentarians were – unusually – required to vote by name. Only 13 outed themselves as opponents of the army. Later, two parliamentarians confessed anonymously to Swiss television that they had voted for the army and against their personal convictions out of fear they might not get re-elected.

The career of the historian Jo Lang, who later became a Green Alternative parliamentarian, was forever bound to the GSoA. For him, there is no doubt that “this vote result liberated German-speaking Switzerland from the Cold War”.

Of course, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Warsaw Pact influenced the result of the vote. On the other hand, Lang thinks the revelation, in the week before the decisive vote, that the Swiss intelligence services were monitoring about 900,000 people had a negligible impact. The report by an investigating commission on the so-called Secret Files Scandal was too close to the vote, he says.

“The fall of the wall ended the Cold War mindset, not the initiative,” counters Kaspar Villiger, the cabinet minister in charge of the military at the time. He attributes the high percentage of yes votes to “a reaction reflecting all kinds of disgruntlement about concrete experiences in the army”.

The “unexpectedly high approval” helped Villiger to address reforms, he says. “The need for reform became evident even to the most dyed-in-the-wool military minds.”

‘Symbolic’ for the era

Was the high approval rate for abolishing the army just a symptom of a shifting geopolitical landscape? Opinions are divided.

Presence SwitzerlandExternal link, the government agency entrusted with promoting Switzerland’s image abroad, writes that the “respectable success” was “symbolic” for the fall of the Wall. Today, the army is a fifth of the size it was 30 years ago. Since 1996, Switzerland has offered a civilian alternative to military service. A career as an officer is neither a guarantee nor a requirement for a professional career, and conscientious objectors need only put a cross on a form.

More than one million people took part in breaking a taboo in 1989 with their votes. The initiative mobilised everyone else too: the first initiative to abolish the army had a turnout of 70%, the third-highest ever.

So was the “sacred cow” slaughtered 30 years ago? “A taboo was broken, even if we didn’t manage to slaughter the sacred cow,” says Jo Lang. Like Renate Schoch, Marc Spescha and Oliver Krieg, Lang remains convinced that Switzerland doesn’t need an army.

More

Defining victory in a direct democracy

(Translated from German by Catherine Hickley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.