Complex laws and ignorance: the obstacles that hinder citizen participation in Mexico

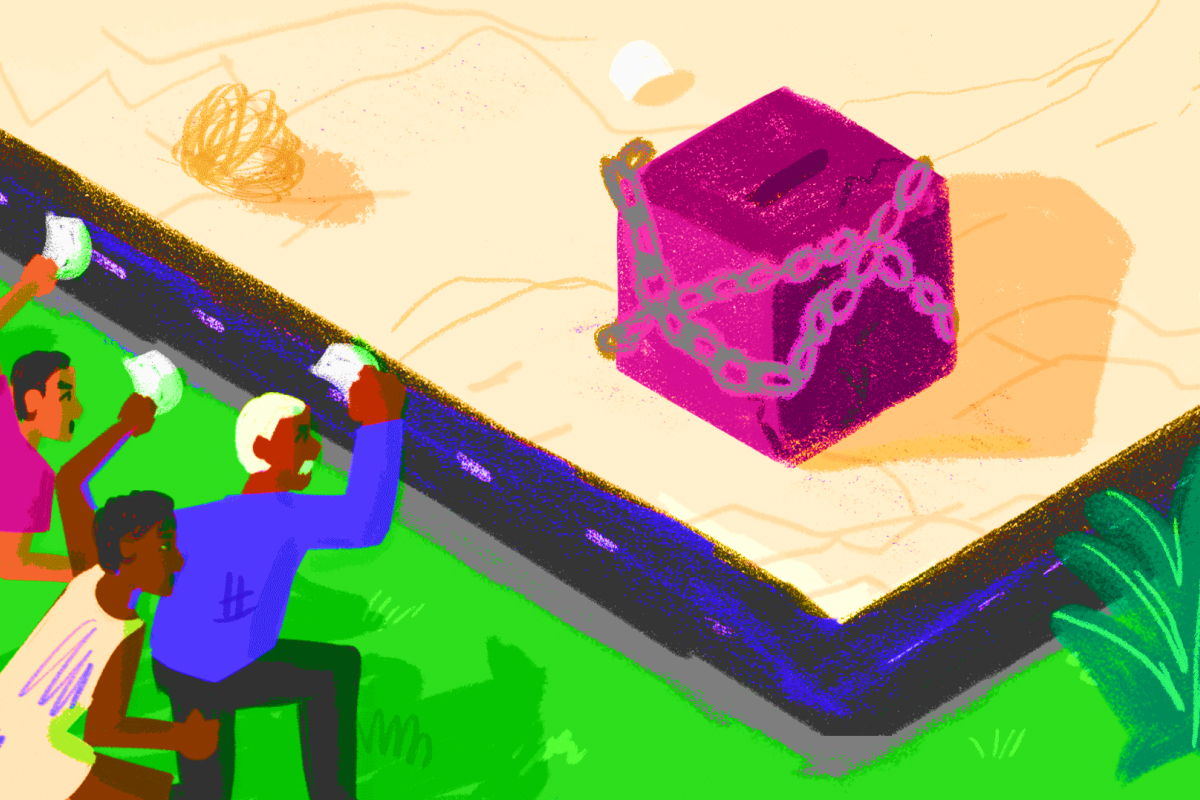

For some Mexicans, citizen participation tools provide a way to drive social improvements; for others, they are “mechanisms with padlocks to prevent them from being activated”.

It is late afternoon on December 17, 2019, in downtown Zapopan, in the Mexican State of Jalisco. “We are about to complete the 518 signatures needed to submit the city council’s decision to a plebiscite!”

These were the words of university student José Martínez, the main instigator of the petition for a plebiscite to prevent the construction of a series of apartment blocks, a hotel and a shopping centre in Plaza Los Arcos in Zapopan.

“We oppose this decision by the city council because this is public space. 86% of this area belongs to the municipality. It belongs to the citizens,” the young man emphasised.

The university student, wearing a white shirt and straw hat, held a placard that read “No to the property deal in Plaza de Arcos”, as he collected signatures together with many other local residents. The issue was pressing. They had only 30 days to submit signatures in support of the plebiscite against the government’s decision to hand the public plot over to private hands.

On December 23, 2019, José delivered 707 signatures to the Electoral and Citizen Participation Institute (known by its Spanish acronym, IEPC) of Jalisco, for it to check that they complied with the rules and that the plebiscite procedure could thus begin.

Of the 707 signatures that the young man handed in, 641 were valid, meaning that the petitioners had received more than the requisite citizen support of 0.05% (518 signatures) of the electoral roll in Zapopan municipality.

On July 14, 2020, the Jalisco IEPC established that the documentation complied with the legal requirements and referred it to Zapopan’s Municipal Council for Citizen Participation – which, after almost nine months of analysis, decided that the plebiscite petition was inadmissible. Meanwhile, building work on the site had progressed significantly and the project had been modified, according to José, who is still upset about the decision today.

“In the end it was a great disappointment, because it is very nice to boast about progress in citizen participation on paper, but in reality it is not happening. The mechanisms have padlocks to prevent them from being activated and to protect the politicians in office”, says the university student, who is about to complete his master’s degree in public policy.

Is it, we ask the experts, the design of these mechanisms that makes it impossible to challenge a government decision, and is this the reason why citizens use them so little?

“That may be one reason, among others. But we cannot generalise here, as each town has a different regulation with different instruments,” explains Yanina Welp, a researcher at the Geneva Graduate Institute’s Albert Hirschman Centre on Democracy.

Each entity of the United Mexican States has its own citizen participation mechanisms, which vary in number and form according to the local laws. They started to be introduced at the State level in 1994. By 2016, all the States had integrated one or more instruments into their constitutions, as shown in this box compiled by Mexican political scientist Martha Sandoval, a scholar on the subject.

Ignorance of the instruments or their rules and the capacity for collective action by their promoters are other factors. “Certainly, their design, the ease with which they can be activated and the time needed to do so, as well as the trust people have in the different mechanisms, determine whether they are actually used or not”, explains Welp, who has studied these tools in different parts of the world.

David Altman, a political scientist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and one of the architects of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) research project, agrees with Welp. “If you can’t play with the toy they’re showing you, in the end you’re better off opting for something else.”

“In Mexico, as in other countries, some citizen participation mechanisms are designed so that they are not used, because the obstacles for citizens to apply them are very subtle and well thought out. The same occurs in Ecuador, which also has many institutions of direct democracy”, the expert in comparative politics explains.

To date, he continues, “there have been very few cases where the citizens themselves have managed to bend the authorities’ arm and obtain something concrete. In Mexico, there has still not yet been a complete experience of the citizens imposing themselves against the authorities in charge. At the national level in Mexico, there has not been a single case – except for this event last year, which was called a recall referendum, but which had a much more plebiscitary flavour than anything else”.

“The transition to democracy in Mexico took place reasonably recently. In Mexico, direct democracy is in its infancy, and democracy in the broader sense also. In other words, the country still has a very weak, very incipient experience in the use of citizen participation mechanisms”, he says.

Lastly, the political scientist points out, a country’s democratic development is not only measured by the use of these tools. “There are many very strong democracies that have no instances of direct democracy at all. It is not a prerequisite for human freedom and equality.”

This article is the product of a journalistic partnership between Animal Político and SWI swissinfo.ch, aimed at sharing viewpoints on the workings of democracy, the people who drive it, and direct democracy tools in Mexico and Switzerland, seen in a global context.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.