Democracy in a passport

On September 15 Switzerland is launching the Swiss Democracy Passport. It’s the same red colour and format as the official national passport. But the similarities end there.

The subtitle on the cover makes it clear what the red book is about: “Guide to Modern Representative Democracy with Initiative and Referendum”. Available in English, Switzerland’s Democracy Passport is designed to be distributed outside the country’s borders.

The passport, a 48-page brochure, gives compact information and insights about Swiss democracy in texts, pictures and graphics. “With the Democracy Passport, we want to counter a major, widespread misunderstanding that direct democracy and representative democracy are mutually exclusive,” says Adrian Schmid, president of the Swiss Democracy FoundationExternal link, which is publishing the passport with assistance from the University of Bern.

Switzerland demonstrates that direct and parliamentary democracy “not only complement each other, but they also support each other,” says Schmid.

The passport is being presented on September 15 at the Polit-Forum Käfigturm in Bern in the context of International Democracy Day, which the United Nations introduced in 2007.

It will also be presented at two further international events in Switzerland: the International Forum of the Swiss Democracy Foundation, for which SWI swissinfo.ch is the media partner. This takes place on September 24 and 25 in Zofingen, in Canton Aargau.

The star of the event is the German-American political scientist Yascha Mounk. With his book “The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It,” published in 2018, he has become one of the most important voices in the current debate on democracy.

Mounk will take part in a panel discussion on the subject “Democracy Takes the Coronavirus Test,” moderated by SWI swissinfo.ch editor-in-chief Larissa Bieler.

The tenth world conference on civic rights will take place next September in Lucerne. The Foundation is one of the organizers of the Global Forum on Modern Direct DemocracyExternal link.

Swiss embassies to distribute the passport

The Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs will distribute most of the first 2,000 copies of the passport in Swiss embassies around the world. The target audience is people with an interest in democracy working in politics, business, education and civil society.

The funding is provided by the Swiss Democracy Foundation, although a contribution will also be made by the customers – these include the federal government and the city of Lucerne. The city will display the passports at the 9th Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy, which takes place there in September 2022 (see below).

swiss-democracy-passport-integrale-version-als-pdf-data-46918861.pdf?ver=c8558ed0

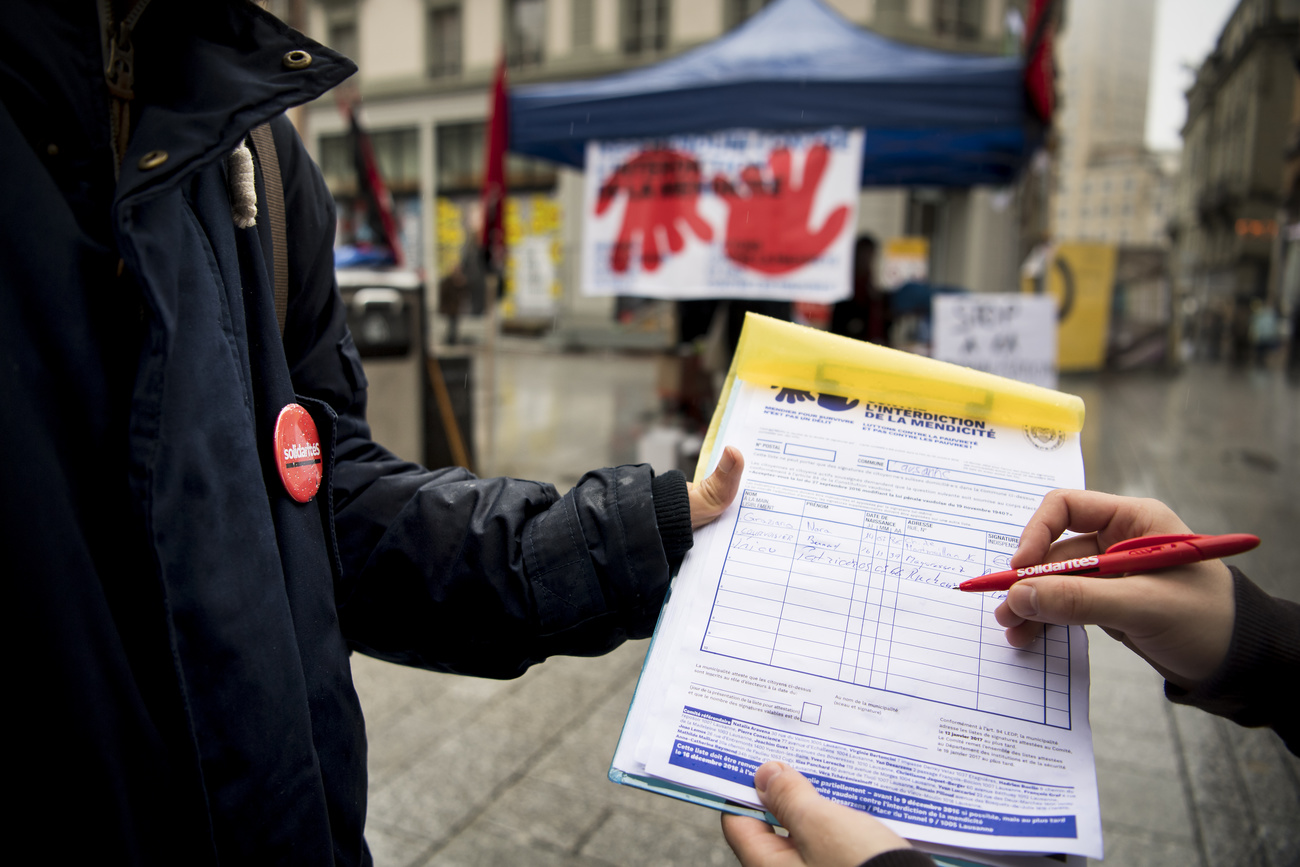

Given the pressure on democracy and freedoms, the passport is not just about information but also about empowerment, the initiators say. “The passport is a kind of toolbox,” says Schmid. “With the instruments of direct democracy described inside, minorities can try to find majorities for their causes.”

Getting the population on board

Promoting democracy abroad is a fundamental part of Swiss foreign policy. It is also anchored in the constitution.

Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis has highlighted the key arguments for why democracy is important in the preface:

- Direct democracy increases popular support for political decisions.

- It forces all those involved to make compromises in order to secure majorities on specific issues.

- The combination of direct democracy, federalism and rule of law ensure that minorities have a voice and are protected.

Cassis also points out that direct democracy can present a challenge for foreign policy. Especially in times when “domestic and foreign policy are more interwoven than ever before.” New instruments such as soft law – quasi-legal instruments that are not binding – have allowed quick foreign policy responses to global problems. But such non-binding agreements, statements of intent, or guidelines “raise valid questions about democratic input in their formulation”.

For Cassis, a challenge of a very different sort is posed by China, with which Switzerland has traditionally maintained good relations since 1950, when it was among the first nations to recognise the People’s Republic.

Cassis acknowledged increasing human rights violations in China in 2019. He adds that Switzerland should be firmer in representing Swiss interests and values in relations with Beijing. By that he is not referring to the distribution of the new Swiss Democracy Passport, but to strengthening international law and the multilateral system.

The Swiss Democracy Passport is the fourth version of this brochure.

The first democracy passport was issued in the Swedish city of Falun.

After that came the European Union’s democracy passport, available in 23 languages. With more than half a million issued, it has the highest print-run of any EU document.

Since 2017, there is also a global democracy passport, available in several languages including Chinese.

The inventor of the democracy passports is the Swiss journalist Bruno Kaufmann, who has also worked for decades as an international correspondent for SRF and SWI swissinfo.ch.

“It all began when a Swedish secondary school teacher complained to me that she didn’t have a simple teaching aid for teaching politics,” Kaufmann says.

“On a European level especially, the democracy passport has helped ensure that new instruments such as the European Citizens’ Initiative have become much better known.” That is shown in the sharp increase in use of this cross-border civic right, he says.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.