Historian casts doubt on Swiss reverence of direct democracy

Even if the symbolic value of citizen participation in decision-making should not be underestimated, the actual importance of direct democracy in Switzerland is often exaggerated, claims leading Swiss historian Thomas Maissen.

An interview with the Paris-based academic, published in in a German-language Sunday newspaperExternal link in Switzerland last month, prompted two days of considerable reaction by readers before fizzling out.

Traditionalists and other unconditional supporters of direct democracy may have bristled after reading the article’s headline: “The Swiss overrate direct democracy.” In the interview, Maissen is also quoted as saying that “direct democracy is more symbolic than we admit.”

Another perceived provocation might be Maissen’s reference to nationwide ballots on seemingly minor issues, including the initiative aimed at promoting cows with horns, rejected by Swiss voters last November.

In the wide-ranging interview, the 56-year old historian with an academic career at universities in neighbouring Germany, France and Italy, goes on to explain what led him to the conclusions.

Not exclusive

He says direct democracy is by no means the sole distinctive factor that contributed to Switzerland’s peaceful and prosperous development over the past decades.

He highlights Swiss multilingualism – there are four national languages: German, French, Italian and Romansh – the federalist structure that delegates power to the 26 cantons, as well as local autonomy that allows municipalities a say in political and administrative issues. Another key building block is the practice of consensus and compromise, he says – the search for an agreement acceptable to all sides.

Maissen warns against considering Switzerland as extraordinary in Europe.

“The French are also convinced that they are a ‘special case’. They have good reasons to claim this status, but so do the Germans and the British,” he says. “What’s supposed to be the norm in Europe? I don’t know,” he concludes.

He also draws attention to the number of laws passed by parliament each year compared with the limited number of popular votes.

Opposition instrument

Maissen goes on to explain possible reasons for Switzerland’s tendency to overrate direct democracy. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he turns to history, notably to the 19th century when modern-day Switzerland was founded.

“Direct democracy was the tool of the opposition against the ruling Liberal elite,” he says. Different groups, both progressive as well as conservative forces, used citizens’ participatory rights to become part of the government.

In the 20th century, the People’s Party added another element, declaring the people the ultimate authority – a move that came at the expense of parliament, the supreme court, and the government, according to Maissen.

He adds that such a perception of direct democracy as the instrument of the people also serves particular interests. The rightwing party is unlikely to ever hold a majority in parliament, the courts or in government, but it has succeeded in winning nationwide votes on several occasions. Initiatives to expel convicted foreign criminals, the re-introduction of immigration quotas, and a ban on the construction of new minarets are three cases in point.

“Therefore, it is tempting for them to say: This is what really counts.”

Maissen doesn’t exempt the political left, saying that both the Social Democrats and the Green Party are also unconditional supporters of direct democracy, even if they don’t glorify the institution. Instead they see it as one of several interdependent factors, he argues.

Power of symbols

Despite his apparent attempt to demystify direct democracy, Maissen stresses the symbolic importance of citizens’ participation in politics.

“It is terribly important for Swiss citizens to identify with the state because we then believe it is our state and that we are partly also decision-makers,” he says.

Referring to the current street protests by citizens against state institutions in neighbouring France, Maissen says a closer identification with the state could also be beneficial for that country. Though he is sceptical about whether the introduction of more direct democracy – that is, nationwide votes on specific issues – would be the solution for France.

He moots the idea of organising a form of public consultation, a refined type of plebiscite which goes beyond the government submitting certain issues to a vote.

As for the political situation in Britain, Maissen doesn’t share the opinion that the 2016 ballot on whether to remain in or to leave the European Union should be a one-off.

“It was a legitimate decision by voters to leave. But it is equally legitimate to have another vote once it is known what the agreed terms for [quitting] are.”

Comments

The interview prompted nearly 100 online comments, though, at first glance, Maissen doesn’t seem overly impressed by their volume or content. He says he can’t help feeling that, as usual, many commentators talk amongst themselves rather than about his statements in the interview.

It is indeed striking how few readers refer to specific points made by Maissen.

Several commentators express their general approval for his stance. More often, however, critics take issue with Maissen’s opinions, notably as a supporter of Swiss membership of the EU, and his outside view of Switzerland.

It is perceived as “leftwing” and “anti-democratic”, underestimating Swiss-style democracy.

More

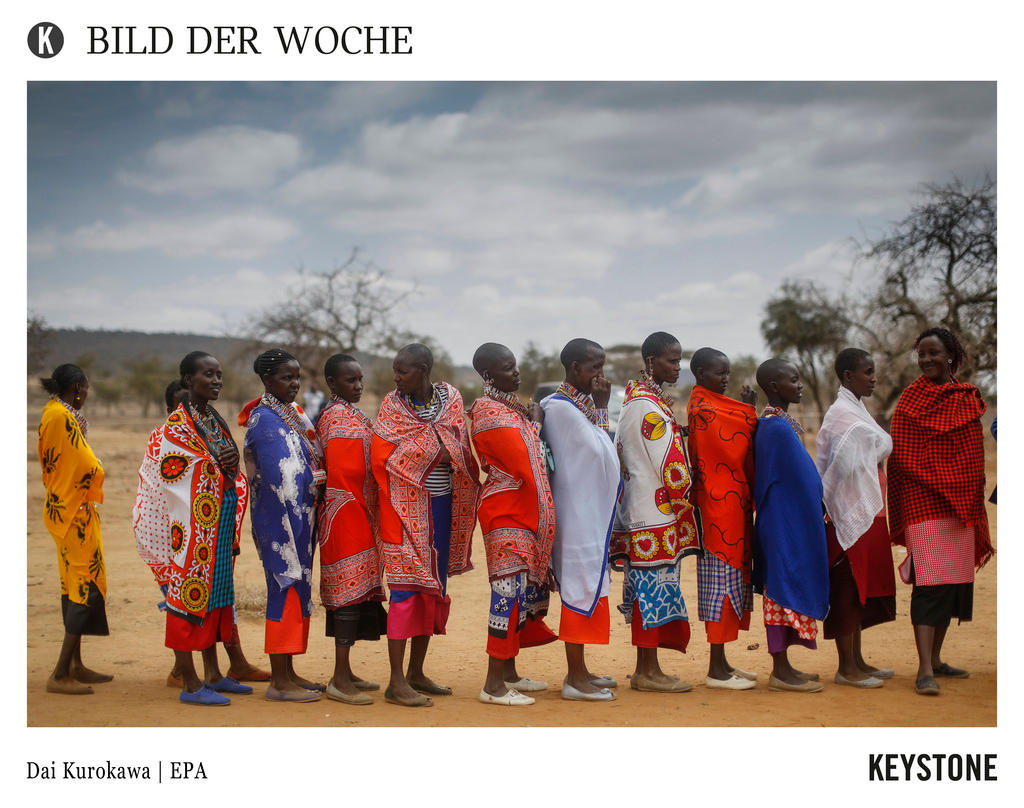

My vote counts: having a say around the world

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.