From Budapest to Helsinki – how cities are the new torchbearers of democracy

Around the world, democracies are under attack. In Europe, progressive cities such as Budapest, Amsterdam, Helsinki and Lausanne are rolling out measures to counteract autocrats and populists.

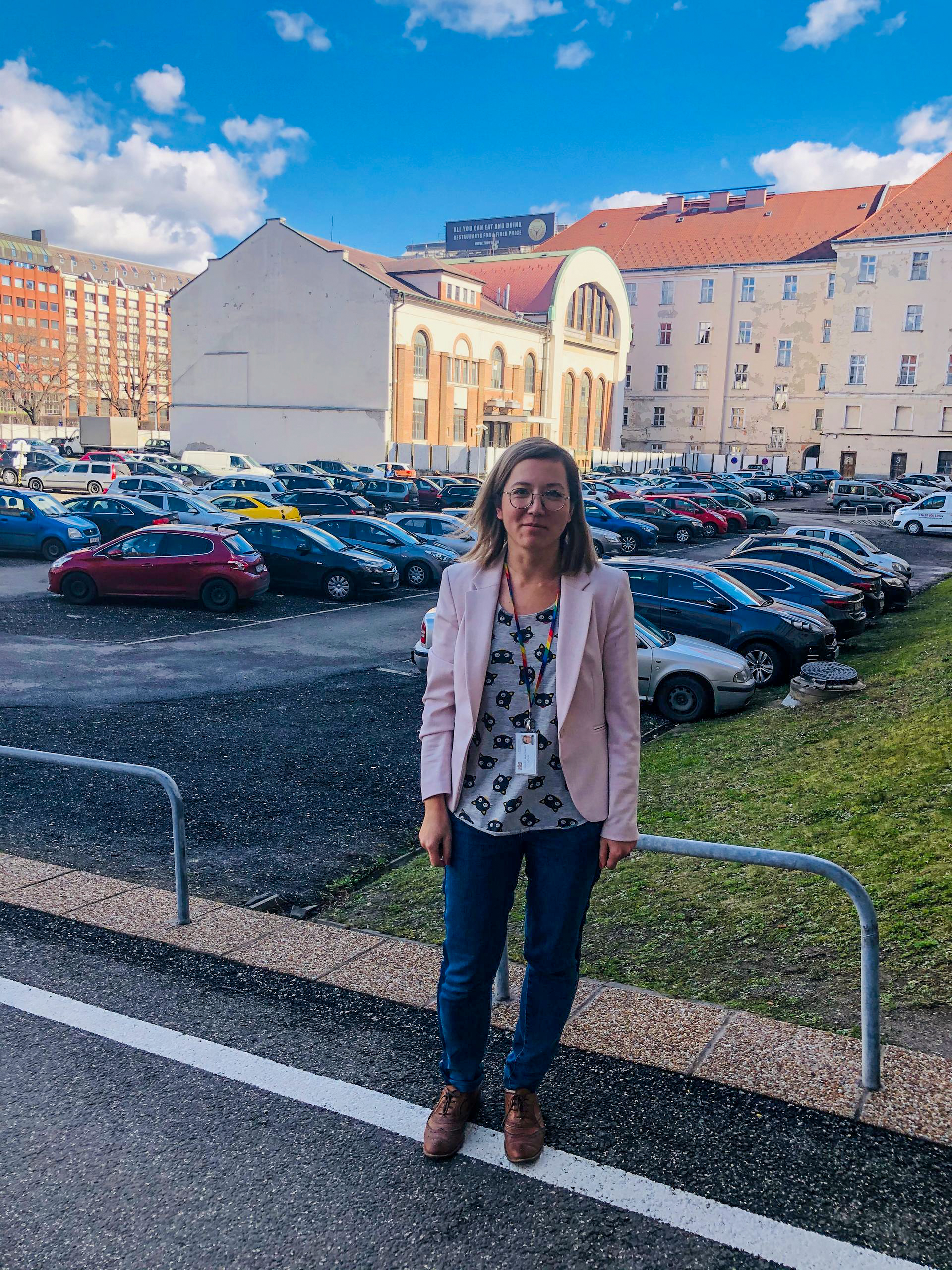

Taking on a strongman in a country that has become an illiberal democracy is no easy task. But Marietta Le is undaunted. She oversees civic engagement in the Hungarian capital, Budapest, a liberal bubble in a country where rightwing conservatives have won the last three elections by landslides.

“Budapest’s new community centre will be built here,” says Le, pointing proudly to the parking lot. She looks very small standing on the square in front of Budapest’s City Hall. The huge complex in the heart of the city of more than two million people looks rundown. That decay mirrors the deteriorating health of democracy in the central European nation of Hungary.

Fifteen years have passed since the Dutch star architect Erick van Egeraat won the competition to design and restore the giant complex that spreads across 120,000 square metres. But he has not been able to lift a finger as Budapest, the European Union’s ninth-largest city, does not have the necessary funds to afford his services.

In the meantime, Viktor Orbán has served as Hungary’s prime minister for 12 years. He and the ruling Fidesz party have used that time to rig electoral laws to their advantage, limit press freedom and slash government funds for cities and communities. Some see the latter as a problem from a global as much as a local perspective.

“But it’s the cities that offer solutions to global challenges,” says Oliver Pilz, manager of the newly established “Office for City Diplomacy” in Budapest. Pilz cites climate change, the migration crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic as key examples in the European context.

Budapest: local democracy in an autocratic state

On the banks of the Danube River, Budapest is at the crossroads of a broader confrontation between democratic and authoritarian forces across the globe. Not far from the capital’s City Hall, a former military hospital, sits the Hungarian parliament, known locally as the Országház, or country house in Hungarian.

It too has fallen into disrepair. Inside, Hungarian legislators have granted sweeping powers to Orbán, the premier who has largely succeeded in turning Hungary into the “illiberal democracy” he infamously promised in a 2014 speech.

This is partly why the renowned Gothenburg-based research institute “Varieties of Democracy” (V-Dem) has rated Hungary as the first European country to become an authoritarian regime rather than a democracy. This rating, however, only applies to countries, not to cities.

“In Budapest, we do everything to promote freedom and democracy,” says Le, a senior advisor to the mayor of Budapest, Gergely Karácsony, who came into his role in 2019 in a surprise victory made possible by the support of a liberal coalition.

The city, she says, upholds democratic values by holding regular citizens’ meetings, a participatory approach to budget allocation and referendums on key decisions.

Budapest’s ruling city coalitions want to promote this approach within Hungary and across Europe.

More

Fifty shades of democracy: can you measure people power?

And that’s where city-level diplomats such as Oliver Pilz can play a role.

“We have established an international league of free cities which aims to access European funding directly rather than through national governments,” he explains. So far, so good. Thirty-six European cities have joined Budapest’s campaign “Direct European Funding for Cities”, while 25 mayors from all over the world have signed the “Pact of Free Cities”, a cooperation agreement to share information about best practices in urban development, mitigating the housing crisis and global warming.

Traditional diplomats also believe in the cities’ potential to save democracies. “I am more and more convinced that cities are not just the cradles of democracy, they have the power to protect and strengthen them,” says the former Austrian ambassador to Slovakia, Helfried Carl.

“Cities display today what democracies could look like tomorrow: more inclusive, more participatory, more accessible and more gender-balanced,” he adds. The 53-year-old is at the helm of the non-governmental “European Capital of Democracy” project. This initiative is coordinated by the “Innovation in Politics” institute in Vienna.

“Cities with a good democratic track record that invest in participation infrastructure can apply for this title,” Carl explains. He says Amsterdam, Helsinki, Mexico City and Switzerland’s fourth biggest city, Lausanne, are good examples that demonstrate the potential of capitals and major cities for promoting democracy.

Democratic ambition and a strong drive for innovation are not only in high demand in Eastern and Central European countries like Hungary, where governments often violate liberties and human rights. Even though their starting position is different, citizens in established Western European democracies are skeptical when it comes to the health of their democratic institutions.

Look at Switzerland. Women were not granted the right to vote until 1971, and 37% of the population is still not eligible to vote.

Lausanne: inclusive pioneer

The situation is different in the city of Lausanne, which is a pioneer in the political inclusion of its citizens, regardless of their national origin

It is a practice that David Payot, who oversees democratic issues at Lausanne’s city council, believes in deeply although it has not been embraced by other cities in Switzerland.

“Democracy is not just about making common decisions,” says Payot. “It’s about acting together, which means everyone should be able to participate.”

More

A global stress test for freedom of expression

Lausanne has not only introduced voting rights for foreigners who have been in Switzerland for ten years or longer, the municipality also offers foreigners other opportunities to participate in the city’s political life as well.

“Everyone living in Lausanne, no matter where they are from, how long they have been here or how old they are, have the right to vote on participatory budgeting*,” explains Payot. The 43-year-old, who has been active in the local politics for a quarter of a century, has come to the conclusion that “Lausanne is a place where democracy is at its best”.

Amsterdam: opposing the dismantling of democracy

Tensions between national and municipal governments are even more pronounced in the Netherlands. It is the first European country to abolish national direct democratic rights shortly after they were launched. Citizen-initiated referendums were introduced in 2015 only to be abolished again by the Dutch parliament three years later.

“The government did not like the referendums that were launched,” political scientist Niesco Dubbelboer told SWI swissinfo.ch on a walk along the Amstel River in Amsterdam.

After this “democratic faux pas” the first female mayor of the Dutch capital, Femke Halsema, stepped in and drafted a new city constitution with Dubbelboer’s help. Once the new constitution comes into effect on February 1, 2022, the nearly one million citizens of Amsterdam will get four new popular voting rights to have a say in local politics. With this move, Amsterdam takes a clear political stance against dismantling democracy on a national level.

Another experiment with democratic decision-making is underway further north. In Finland, a strong administrative system controls the country’s political life, which leaves the citizens little power to act. The country’s capital Helsinki came up with a rather unusual idea and introduced the “Democracy Game,” a card game that allows participants to be involved in all aspects of decision-making at the local level.

“Five years ago we got the first politically elected mayor,” says Johanna Seppälä, who has been coordinating democratic development in the municipal council since 2018.

This elected mayor did not abuse his democratic legitimacy. Instead, says Seppälä, he made sure that all 40,000 city employees were trained in ‘accessible administration’ by means of a board game. This triggered a complete change in culture.

“Active and interested citizens who the administration used to consider as disruptive are now welcome,” she says.

Not only in Europe, but also across the world, cities are the engines of democratic developments such as equal rights between the sexes. Women have risen to the top and now run major cities in countries where men traditionally held most government positions. They include Claudia Sheinbaum in Mexico City, Claudia Souad Abderrahim in Tunis and Yuriko Koike in Tokyo, to name a few.

Governments across the world are taking note of the potential of cities as a key force for democracy. This is possible even in autocratic Hungary, where opposition parties last autumn organised primaries, lining up several candidates who are active at the local level. One of them, a conservative politician, Péter Márki-Zay, has a decent chance of being elected after having earned a pro-democratic reputation while running the small southern Hungarian town of Hódmezővásárhely.

In these darker hours for human rights and democracy at the national level, local communities are emerging as shining power houses for a better world.

* Participatory budgeting is a democratic process in which community members decide how to spend part of a public budget. It gives people real power over real money.

Translated from German by Billi Bierling

Correction: The river Amstel was incorrectly referred to as River Maas in a previous version of this article.

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!