In Nepal, an uphill battle for gender parity

Female representation in Nepal’s parliament has increased dramatically in the last 10 years. It’s the result of a far-reaching gender quota system in the Himalayan nation that has made the country’s Constitution one of the most politically progressive in Asia. But women politicians and rights advocates say that true equality remains a long way off.

“It’s still not easy to make people understand that women, like men, are respectable citizens, that they should be treated equally, that the society should be serious about creating an environment ensuring their participation,” says Tham Maya Thapa, one of three women in the Nepali federal government.

As the minister for women, children and senior citizensExternal link, it is her job to find ways to overcome traditional patriarchal mindsets in society. Despite laws protecting women from violence and discrimination, that mindset often prevails, she says. This includes turning a blind eye to issues such as sexual harassment or menstrual isolation. Meanwhile, all forms of gender-based domestic violence and discrimination endure.

The minister is one of a dozen women’s rights advocates we spoke to in Nepal, who said that constitutional reforms and legislative measures are necessary but not enough to bring about that societal changes required to achieve true equality. Despite the legislative measures in place, women’s real participation in political decision-making remains limited.

The Himalayan nation has only about a decade ago found peace as a federal republic. The new Constitution, passed in 2015, ensures that at least 33% of all lawmakers in parliament are women at the national level. At the local level, minimu, 40% of all leading political roles should be filled by women. That is a considerable change. Back in 2007, only 6% of Nepal’s parliament was female.

There are not many other countries that have enshrined women’s political participation in the Constitution and made their inclusion in decision-making legally binding. This was intentional, addressing longstanding discrimination based on gender and caste — a person’s position in society. It also signals a departure from the past when women have had traditionally fewer opportunities to make their voices heard.

The Constitution requires a woman to serve either as the country’s president or the vice-president. The same holds true for the president of the parliament and the chief of the judiciary. In the municipalities, either the mayor or deputy mayor must also be a woman. Every ward in every municipality has to reserve two seats for women, one of which should be held by a woman from the Dalit caste, a community historically excluded from leadership positions in society.

In addition to gender quotas, the Constitution also established a multi-party democratic system, guarantees free elections with provisions to safeguard various human rights including freedom of the press. These changes saw Nepal rank as the second-most progressive Asian country after East Timor in terms of women’s role in politics, according to a recent ranking by Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women.

A new generation of women politicians

Nearly 7,000 of the 13,486 seats won by women at the last local election in 2017 went to members from Dalit communities, according to data collected by the Center for Dalit Women NepalExternal link. These proportional reforms made the participation of Dalit women in politics a reality for the first time.

But the Dalits in particular — Nepal’s most marginalised community — continue to suffer discrimination and violence from the old forms of social hierarchy. It also exacerbates the exclusion of the new group of Dalit women politicians, and the discrimination they face in their office.

They are fighting uphill battles to get heard, respected and followed within their political parties, members of local government, the local communities, and even within their families, rights advocates say. Just this April, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) began supporting She Leads NepalExternal link, a women’s leadership programme for rural areas, to address these problems.

One of these new women politicians is Indrakala Yadav, a deputy mayor in the rural Laximiya municipality.

She was elected for promising new shelters and road construction and because she distributed drinking water to poor women. But she says that the male mayor does not want to work with her on the new budget for local labour policy because he was sceptical of her. The budget was drafted without consulting her, she adds. There are 15 members of the municipal government, and she was the only one excluded from the process — as well as the only women.

Another deputy mayor of the city of Janakpur is Rita Kumari Mishra. When we met her, she told us of the kind of antagonism she experienced when she managed to push through a major road expansion.

“Men took seven years to do 20% of the work, but I did the remaining 80%,” she says. Yet, her difficulties became apparent when a male ward of the city, Sudarsan Singh, cautioned in an interview that “the deputy mayor needs more education and training for her position”.

Such attitudes probably wouldn’t surprise Bimala Rai Paudyal, a member of the lower house of parliament we met in Kathmandu. She says that women’s skills and capacity are often questioned when they want to become politically active. Sometimes, she says, women need to convince family members by telling them about the economic benefits. However, “people never question men’s capacities,” she says — even if women work twice as hard.

Many of the advocates say that fixing the quota system was just a first step. “The democracy is not enough to ensure women’s rights because democracy functions with the majority voice”, says Indu Tuladhar, a lawyer and director of the Himal Innovative Development and ResearchExternal link, an advocacy group.

Much more to be done

So while the country is ahead of its regional neighbours and peers, women rights advocates and politicians across the country say Nepalese society and the government need to do much more to advance gender parity. They all agree that abuse and violence should be punished more heavily, enforced and monitored.

Bandana Rana, a Member of the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)External link, says that the Nepalese Constitution is one of the most progressive worldwide. But, she says, “Nepal is facing challenges because a mechanism to monitor victims and survivors of violence is missing.”

Professor Renu Adhikary, the founding chair of the Women’s Rehabilitation Center (WOREC)External link, an NGO which tries to address the limited influence of women politicians in Nepal, says that legislation is not enough. People’s attitudes need to change.

She argues that “the gender-based violence can only be addressed by changing people’s mindsets.”

Most of the problems start in families and smaller social circles, which are much harder to change than electoral quotas. Domestic violence or rape cases often stay inside the family, Chanda Chaudhary, a member of the House of Representatives, explains, where they often go unseen to a wider public.

A next step would be to ensure that women have the resources and time to participate in public life. Women are still obliged to look after their family and children. Many female politicians face economical problems and need to ask their husbands for permission to run for office, or sometimes even to leave the house and travel. In addition to this, political parties are dominated by men. Chaudhary thinks that financial independence and family support are key factors to advance women’s political participation.

Some activists argue that it is not only up to them to change society, but also up to Nepal’s men. “The men should also help women and stand up for them to address problems and ensure better coexistence,” Dil Kumari Panta a youth leader for the Central Committee of the governing Nepal Communist Party, says.

All agree that it would still take a long time for all Nepalese to be truly equal.

“When my husband asks me for a cup of tea, I prepare it for him after his day at work,” says Bimala Rai Paudyal, the lawmaker. “But I prepare my own tea, even if I am exhausted after my day at work.”

Women in Politics

Currently, only one in four parliamentarians in the world is a woman. In only three countries out of 193 – Rwanda, Cuba and Bolivia – women are more than 50 % of all lawmakers in parliament, according to the study “Women in politics 2019External link” by Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women.

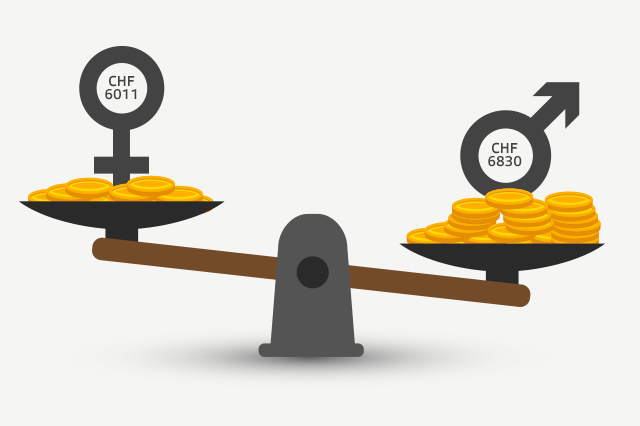

Switzerland does not have a gender quota system. The country ranks 37th globally with a participation rate of 32.5% in the lower house and 15.2% in the upper, according to the study.

There is, however, an extensive grassroots campaign to improve the representation of women in politics and to lessen gender imbalances in the workplace. There was a historical women’s strike on 14 June. Gender equality is a topic of debate ahead of the 2019 parliament election in October.

More

Swiss ambassador to Nepal: ‘We have more to do’ on women’s rights

*This report was produced as part of En Quête d’AilleursExternal link (Looking Beyond), an exchange programme between journalists from Switzerland and developing countries.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.