Geneva disarmament process targets killer robots

Since the day it opened, the United Nations in Geneva has been the venue for negotiations aimed at preventing war - and, if war can’t be prevented, mitigating its effects on civilians.

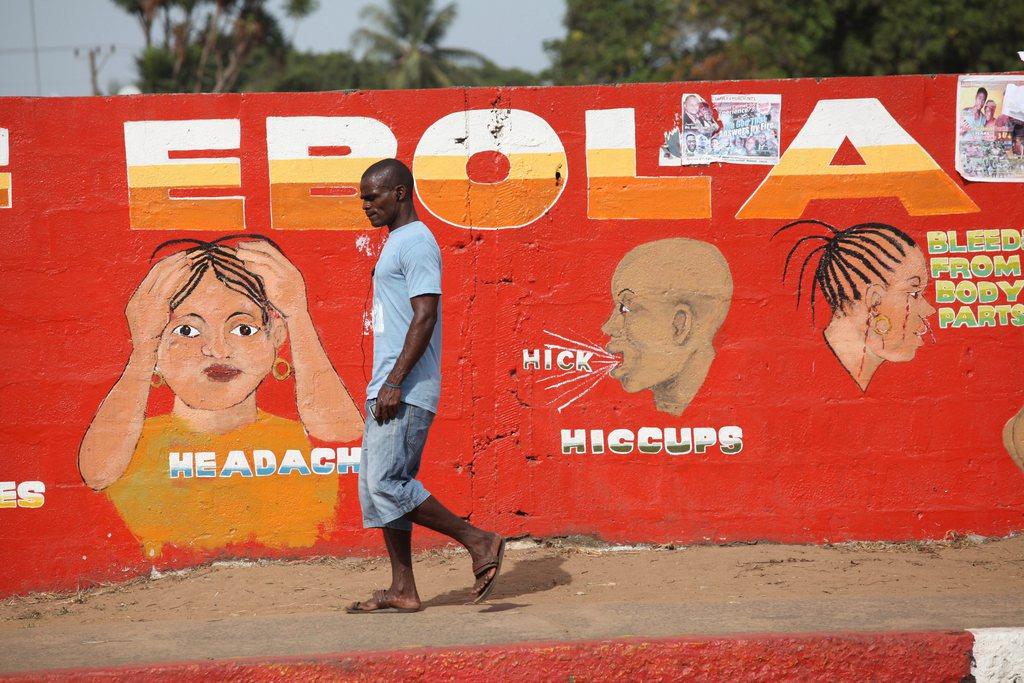

Disarmament has been a key element of those negotiations. From conventions on the prohibition of biological and chemical weapons, to painstakingly slow talks on nuclear non-proliferation, Geneva has been the place where UN member states can discuss their military capability, and try, or at least make a show of trying, to keep the most devastating weapons under control.

This month, the UN’s rather clumsily named Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW)External link is meeting to look at an especially modern issue: Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS), often also known as ‘killer robotsExternal link.’

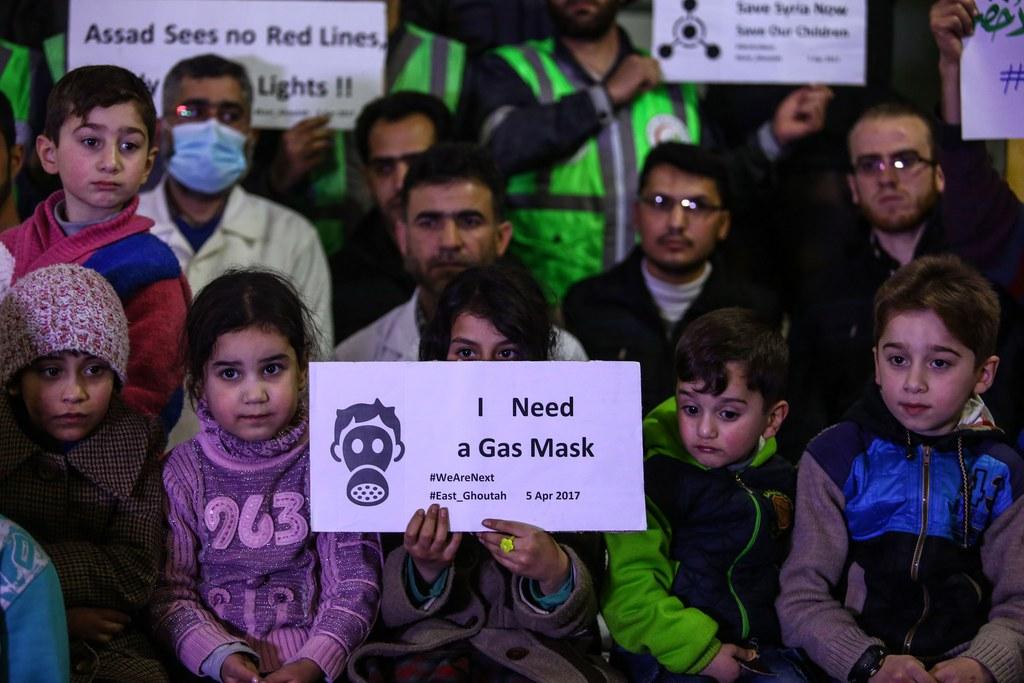

Autonomous weapons are defined as those which can select and engage targets without any human intervention. Although drones of the type used in Pakistan, Iraq, or Syria come close to that, they are not fully autonomous…or not yet.

Slow progress

The CCW has been engaged with the subject for some years now, but, like so many disarmament negotiations, progress has been painfully slow.

Some military analysts suggest there could be advantages to autonomous weapons: they could reduce the risk to soldiers by decreasing the need for their presence on the battlefield, and they could minimize harm to civilians by being less prone to targeting error than mere humans.

Opponents of autonomous weapons however argue that the decision to kill or not to kill must always be taken by a human. They fear that while diplomats dally in meeting rooms, the technology will race ahead, allowing LAWS to be manufactured and even deployed before any agreement on how they should be regulated has been reached.

“We don’t have all the time in the world on this,” said Maya Brehm, of the Swiss branch of Article 36External link, a non-governmental organisation working to prevent weapons proliferation. “This is a problem that has to be solved as a matter of urgency.”

Alarmist scenarios

Opponents of LAWS believe the issue is so urgent that the only way to solve it is a pre-emptive ban. To persuade UN member states that this is necessary, the Campaign to stop Killer Robots made a video to show at the start of this month’s CCW discussions.

In a chilling storyline, it depicts swarms of mini-drones, each equipped with a small quantity of high-power explosives, and each targeting specific individuals using face and voice recognition. The ‘slaughterbots’ as the video bluntly terms them, are used by a variety of groups to kill perceived opponents, including students and human rights activists.

“There was stunned silence,” Stephen Goose, head of Human Rights Watch’s arms division, said of the reaction of UN member states to this scenario. And while Goose agrees the video may be disturbing, he believes that ‘it is meant to alarm people, to wake people up to what can happen, it is realistic, it is based on science, it is an accurate depiction of what could happen.’

And, he points out, all the technology used in the ‘slaughterbots’ is already available, and getting cheaper by the day.

So far, however, just 22 countries (including Brazil, Argentina, Pakistan and Egypt, but no Europeans) have backed a pre-emptive ban. Where there is agreement, even from states which are actively developing autonomous weapons, like the US, Russia, and China, is that they should always be subject to ‘meaningful human control’.

Years of discussion

But campaigners fear that defining the term ‘meaningful’ could take years, thus allowing the countries most keen on autonomous weapons to continue developing them, all the while paying lip service to the UN negotiations on controlling them.

Trying to set an agenda for member states, the Chair of the CCW’s group of experts on autonomous weapons, India’s ambassador Amandeep Gill, has drawn up talking points, and identified areas he wants the CCW to focus on in the months (and possibly years) ahead.

He would like member states to define what exactly a lethal autonomous weapon is, to focus on the ‘human machine interface’ and to come up with ‘policy pathways.’

This is, unsurprisingly, not exactly what campaigners wanted to hear. They would prefer a target date of 2019 for agreed rules on LAWS.

“Diplomatically we could call this ‘incremental progress,” said Stephen Goose. “Or we could say the CCW is aiming low and going slow.”

Abandon UN Process?

Many of the groups lobbying against LAWS are veterans of other disarmament negotiations, and their impatience with the UN process could have consequences.

When moves to ban landmines, and later cluster munitions, became stalled at the CCW, campaigners and likeminded countries simply moved it out of the UN, and drafted international conventions anyway. The result: the Ottawa ConventionExternal link on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines, now ratified by 162 countries, and the Oslo ConventionExternal link on Cluster Munitions, ratified by 102.

So could this particular UN disarmament process also be sidelined?

Stephen Goose suggests that “if it [a possible agreement] is going to be very weak”, or “if it takes ten years”, then campaigners would be tempted to go outside the UN.

But he and others are reluctant to that step yet, partly because so few countries have supported a pre-emptive ban, or even expressed a definite view on LAWS, and partly because going outside the UN would lose the most powerful players in the autonomous field: the United States, China, and Russia.

In such a rapidly moving technological field, which poses enormous moral and ethical questions, everyone agrees the process should be as inclusive as possible. Member states, NGOs, the International Committee of the Red Cross – as guardian of the Geneva Conventions – and military and artificial intelligence experts should all be at the table together.

And so the discussion on lethal autonomous weapons will inch along. In the end, no single group or country is likely to get exactly what it wants. But the UN in Geneva is, for the foreseeable future at least, fulfilling its traditional role of providing a neutral venue where all concerned can talk freely about the most serious issues facing the world.

Such negotiations are “always full of tensions”, said Maya Brehm of Article 36. “And that is difficult for most of us, but it is good that we have a place for them.”

You can follow Imogen Foulkes on twitter at @imogenfoulkes, and send her questions and suggestions for UN topics.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.