Landmine ban: From Utopian vision to global accord

In Geneva this month there is a very special exhibition, highlighting a key moment in the history of disarmament, and the important role Geneva played in it.

On December 3, 1997, over 120 countries gathered in Ottawa, Canada, to sign one of the most far reaching arms control conventions the world has ever seen: the ban on anti personnel landmines.

The exhibition, which moves from Plain Palais to the Place des Nations on December 4th, traces the tireless work of campaigners who first brought their dream to the United Nations disarmament process, through the involvement of major humanitarian organisations like the International Committee of the Red Cross, to the adoption of the convention.

Many of us take the ban on landmines for granted nowadays that it may be hard to imagine just what a struggle it was to get the Ottawa Convention ratified.

“It was totally utopian,” remembers Paul Vermeulen, of Handicap InternationalExternal link Switzerland. “Landmines were everywhere, all countries had them, it took a lot of vision to imagine and campaign for a world without landmines.”

Erik Tollefsen, the head of the ICRC’s Weapon Contamination UnitExternal link, also recalls how difficult it was to try to even control landmines, let alone ban them.

“When I first got involved with landmine clearance and clearance of explosive remnants of war back in the early 90s in Lebanon and then Bosnia, it was like the work of Sisyphus,” he explains.

+ Read about ongoing efforts to clear landmines in Bosnia

“Even though we were working as hard as possible to remove landmines, more mines were put into the ground, we saw the statistics of victims rising from year to year.”

Public Outcry

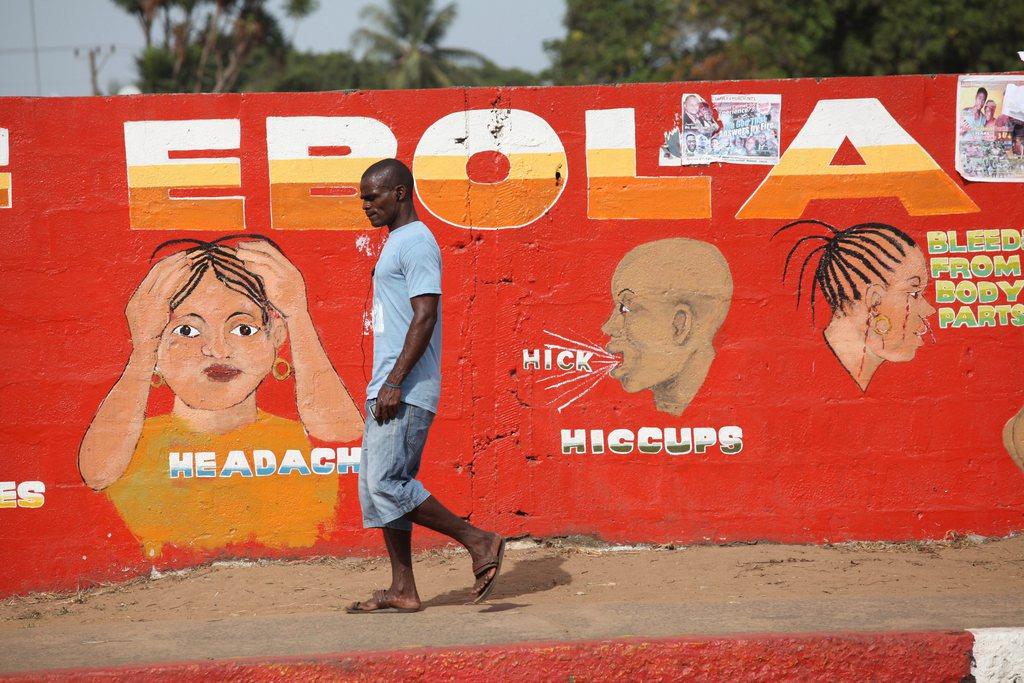

But in the five years prior to 1997, the public outcry over weapons which killed and maimed around 20,000 people, most of them civilians, every year, became louder and louder.

Doctors and aid workers with experience in refugee camps from Thailand to Mozambique to Lebanon brought eyewitness accounts of women and children maimed for life in an instant, because they had, literally, put a foot wrong in their flight to safety.

UN development workers spoke of their frustration at trying to support post conflict countries to regain economic success, when vast tracts of arable land could not be used because they were contaminated by mines.

A key part of the campaign for a ban, says Ambassador Stefano Toscano, who is Director for the Geneva Centre for Humanitarian DeminingExternal link, was the close cooperation between non-governmental organisations, and diplomats representing member states.

“A wonderful partnership was created,” he explains. “It became a blueprint for other campaigns, like small arms, and cluster munitions.”

And so, when member states gathered in Geneva to discuss landmines at the Conference on Conventional WeaponsExternal link (CCW), campaigning groups, while not allowed in the negotiating rooms, still played a huge role, advising diplomats on the effects of landmines.

“Many of them were very moved by what we showed them,” remembers Vermeulen.

But the campaigners ran up against a problem in Geneva: the CCW adopts policy by consensus, not majority. With big players like the United States, Russia, and China in the room, there was no realistic chance of getting a total ban approved.

Instead, some member states proposed agreeing a legal framework for landmines, with strict regulations over the circumstances in which they could be used.

A compromise too far

For campaigners, and for many diplomats, this was a compromise too far. Lloyd Axworthy, the then Canadian foreign minister, invited his colleagues to join a process to draft a convention outside the UN.

An encouraging number of member states, including Switzerland, got behind the process right away, and campaigners like Vermeulen got busy on a global, and very visual, campaign.

“I was thinking what can I do in Switzerland to get the largest number of states to sign up to the Ottawa ConventionExternal link,” he says. “And one crazy dream was to have a huge chair, with one leg ripped off, in front of the United Nations.”

Not so crazy after all: Paul’s design, though originally intended as temporary, has stood in the Place des Nations for 20 years, apart from a brief absence in 2005 when the UN was undergoing renovation.

But it was only one eye catching monument among many. In the months prior to December 1997, pyramids of shoes began appearing in many cities, designed to draw attention to the suffering caused by landmines. Pairs of trousers, with one leg missing, were hung from government buildings.

And, for some, the most iconic images of all, Princess Diana, walking through a minefield in Angola, or visiting mine victims in Bosnia.

Peak Momentum

By December 1997, when member states gathered in Ottawa for the convention signing conference, the campaign had reached peak momentum. 150 countries attended, and 122 signed up to the ban on the spot.

Vermeulen remembers it as an “exhilarating moment…making what some thought was utopian come true”.

In the two decades since, huge areas of land have been cleared of mines, and the number of landmine deaths and injuries has reduced from 20,000 a year to 6,500.

Worryingly though, recently, that downward curve seems to be leveling off, even increasingly slightly. At the same time, funding for demining is decreasing, as some donors perhaps believe the job is done.

At the GICHD, the body set up by Switzerland in 1998 to support demining work worldwide, Stefano Toscano agrees that the goals of the Ottawa Convention have not yet been fully achieved.

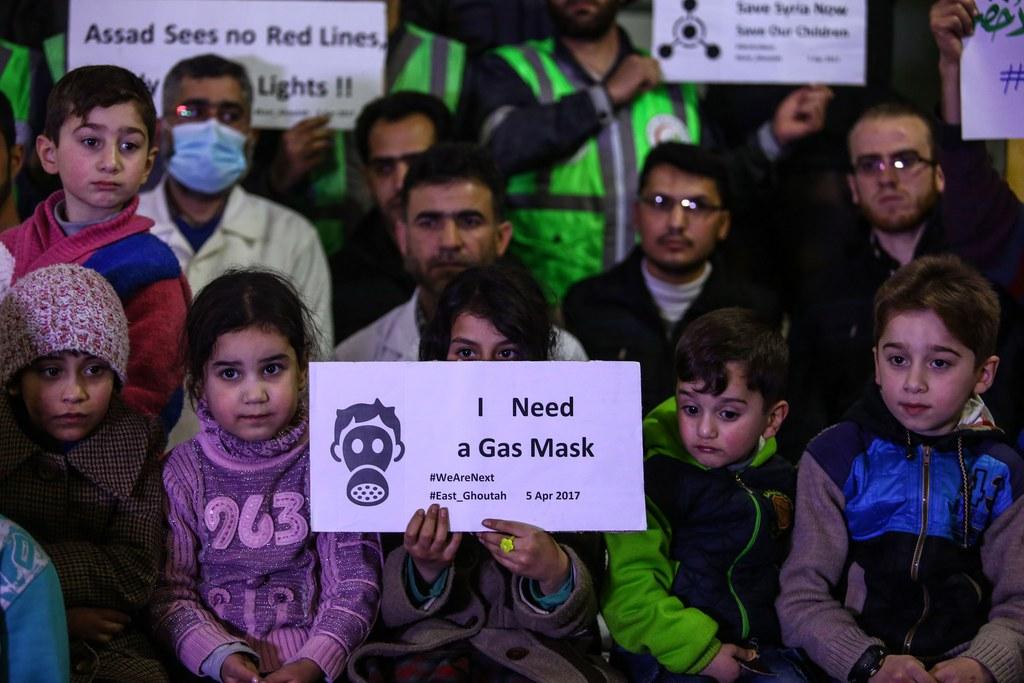

“The problem is still around,” he says. “In fact it has even have got worse because of the new conflicts in the Middle East. We are seeing new contamination in the form of IEDs (improvised explosive devices). It is not just legacy contamination in more than 60 countries, now there is new contamination.”

Erik Tollefsen at the ICRC is also concerned. In Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan, armed groups are increasingly making their own weapons.

“The big problem today is non-state actors,” he explains.

“We see that more, much more improvised landmines, homemade artisanal mines are being used than we are able to clear.”

A recent report from the medical charity Medecins sans FrontieresExternal link (Doctors Without Borders) revealed that civilians returning to the Syrian town of Raqqa were finding their houses, streets and fields littered with booby traps, mines, and unexploded ordinance.

Some of that may be the natural fall out of war, but the ICRC is clear that under the terms of the Ottawa Convention, any improvised explosive which is triggered by the victim falls under the terms of the ban, just like a landmine.

So, a great deal remains to be done to truly achieve Ottawa’s vision of no landmines, and no landmine victims. The 20-year anniversary, and Geneva’s exhibition, is a serious message as well as a moment for celebration.

You can follow Imogen Foulkes on twitter at @imogenfoulkes, and send her questions and suggestions for UN topics.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.