What will our jobs be like in the future?

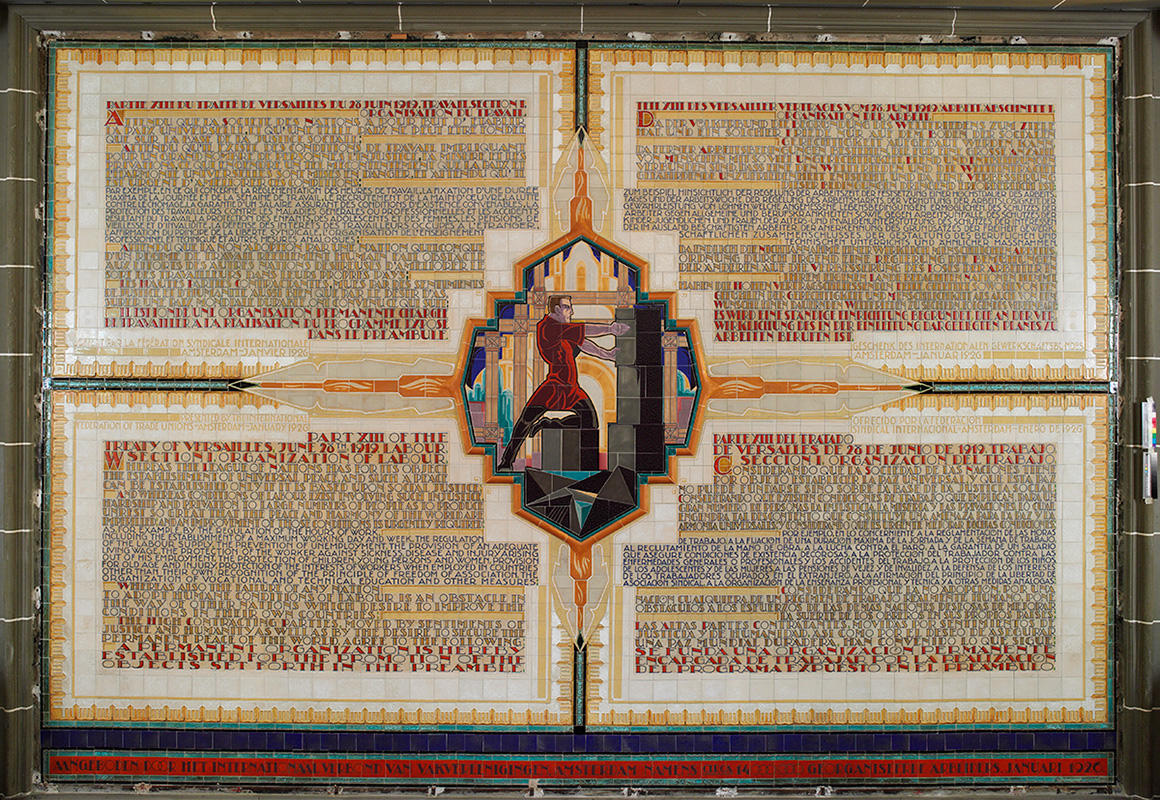

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) is 100 years old. For a century the ILO has been defending the rights of workers, tirelessly campaigning for safe working conditions, against child and slave labour, and for an end to workplace discrimination.

At its annual conference this monthExternal link, the ILO marked its centenary External linkby looking firmly to the future, at the rapid technological changes which are changing the way we work so fast, we sometimes feel we can barely keep up.

An ILO Future of WorkExternal link debate I attended caused me to reflect on how the profession I work in has changed since I entered it.

More

Geneva conference tackles workplace harassment and future jobs

In my very first job in TV news, we had three-man crews (and I use that word advisedly, there were no women on the TV crews at the company I first worked at). A cameraman, a sound recordist, and a ‘sparky’ to do the lights and other electrical stuff.

Our TV pieces were edited on wheezing old U-matic tape: state of the art at the time, other TV stations were still using 16mm film.

Fast forward a year or two to Swiss Radio International, and we were recording on ¼-inch tape Nagras, or Sony cassette players. Everything was edited on ¼-inch using a razor blade and a bright yellow grease pencil.

New technology

Now, I carry an entire TV and radio studio in my rucksack. I can go live on TV or radio from my mobile phone. I have interviewed ambassadors using my iPhone, then airdropped the interview to my laptop, quickly cut out the best bits using software we would have viewed as wishful fantasy not so long ago, and transferred, in the space of a few seconds, the whole thing to the BBC news server in London.

More

Has the global labour organisation advanced workers’ rights?

Last week, covering the Women’s Strike in Switzerland, I had a cameraman. He was also the sound recordist, the producer, and the engineer ensuring our live links worked. He had a Steadicam the size of a fountain pen, it produced fantastic pictures.

It’s fantastic in some ways: each bit of equipment is lighter, but there is more of it. It is more electronic, less mechanical. Fixing a faulty bit of kit is not something I’m so keen to try these days.

And of course, the new technology has changed journalism fundamentally. We live in what some of us call the ‘tyranny of 24-hour news’. Since the technology is there to allow us to go live anytime anywhere, why shouldn’t we? Forget dinner time, sleep time, birthdays, Christmas. And sometimes, because we have to work so fast, and often alone, forget quality.

Protecting decent work in the future

That is why it is so important that the ILO is debating this topic. Everywhere now we see how new technology is changing our working lives. At our supermarkets, we can check out ourselves. The staff (mostly women) who used to sit at the cash registers are watching us do they job they once did, just in case we need any help. The more we get used to the new self-check outs, the more redundant the old cashiers become.

And still despite the examples I have given, I’m underestimating the change. I heard an expert on the future of work this week suggest that 65% of today’s primary school children will grow up to do jobs that don’t even exist yet.

At the ILO debate, we were treated to some real expertise on what the world of work can expect in the decades to come, and some cautionary tales about how to ensure that decent work can be maintained, even promoted, during and after this technological revolution.

Eric Manzi of the Rwanda trade union CESTRAR External linktold us about a once booming jobs market there, under which many young people had left rural livelihoods to join companies selling mobile cash credit cards. They are useful things, and have become popular in many African countries. Selling the cards paid better than tilling the fields. But those cards have a pretty short shelf life: they are already being taken over by mobile phone payment apps.

More

Two-thirds of Swiss see artificial intelligence as job threat

So, what happens to all those card sellers when no one needs the cards anymore? In this situation, Eric Manzi pointed out, retraining is crucial. The same companies who promoted the cards are now offering the new phone apps. They surely have a responsibility to those they employed. People are not outdated technology to be thrown away, instead they should be offered the support to learn a new skill.

The robots are coming

Other speakers on the panel warned of the ‘march of the robots’; the fear that machines will take our jobs. Those supermarket cashiers and cash card sellers will sympathise, but others suggest that new technology, and artificial intelligence, need not be negative. During the industrial revolution there were fears too that unemployment would rise dramatically, but in fact that didn’t happen. Instead the jobs humans changed, and quite often for the better.

Then, there is the question of working conditions. If, as so many people do nowadays, you work remotely, or ‘telework’, how are your conditions, the hours you do, your right to a break, protected? Increasingly, people not only telework, but they work piecemeal, on various jobs for various employers, (this is often euphemistically termed ‘consultancy’). Where does the right to sick pay, a pension, a holiday, fit in here?

And what about ownership of data. This is complicated, but we know how important data has become in today’s global economy. So here is an example, which was offered during the panel by Parminder Jeet Singh, of the Indian non-governmental group IT for Change.External link

Parminder took the example of the ride-hailing firm Uber. Well, they are just cheap taxis, you might think. Not quite. As Parminder explained, Uber’s real asset is ‘the detailed intelligence it builds about a town, its drivers and people, which is systematically and continually accumulated.’ That data helps Uber do business, expand, and plan future investment. So, who owns the economic value of that information? Uber? Or the drivers who provide it?

Tripartite structure

These are the profound, and very complex questions that society, workers, employers, investors, and governments will have to address. Currently, the owners and developers of digital technology and digital platforms such as Facebook are running away, largely unchecked, with the profits, and the data.

It’s been heard, recently, that the ILO, with its tripartite structureExternal link bringing together trade unions, employers and governments, is a bit outdated. Even its vast monolithic headquarters in Geneva suggests an era that is past. Some member states, looking at which UN agency to prioritise, have pushed the ILO down towards the bottom of their list.

But what other agency can so effectively address this question? The future of work affects us all. An organisation that can bring all the actors in the global economy together, from the billionaire software developer to the poverty line phone sales person, to the government regulator, is more necessary now than ever.

As one of the panelists at that Future of Work debate put it, big changes, bigger even than the ones we have seen already, are coming. It will be disruptive, but it must not be destructive.

You can follow Imogen Foulkes on twitter at @imogenfoulkes, and send her questions and suggestions for UN topics.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.