Is there a place for culture in Swiss development aid?

Switzerland is changing its approach to foreign aid to work more closely with businesses and align with the country’s migration policy. Many are wondering where that leaves projects promoting culture abroad.

The right-wing Swiss People’s Party is pushing for dramatic changes to Switzerland’s approach to development cooperation.

In addition to cutting the budget of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC)External link, the largest party in the Swiss House of Representatives is questioning the value of cultural projects that have been a mainstay of the country’s approach to development cooperation.

Early this year, People’s Party parliamentarian Andreas Glarner told the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper that projects involving puppeteers and painters in Tanzania, or actors in Mali and Uzbekistan, have “nothing to do with development cooperation”.

“It’s unacceptable that children are starving in Burkina Faso [while we support cultural projects],” he added.

“One thing does not rule out the other,” argues Regula Gattiker, who leads the culture and conflict transformation programme at Swiss non-governmental organisation HelvetasExternal link. “Experiencing culture is a basic human need.”

Switzerland’s development cooperation is based on several core tenants. “Alleviating suffering and poverty in the world” is enshrined in the Swiss Constitution. The federal law on international cooperation and humanitarian aid also mandates the SDC to support developing countries in efforts to improve people’s living conditions.

A means of expression

Gattiker is convinced that promoting culture has a positive effect on those living conditions through affecting the economic and social development of developing countries. “Artists contribute to innovation and strengthen young people’s personal initiative and self-confidence,” she says.

“Artists often address social trends earlier and differently than others. Culture can serve as a means of expression in societies where political statements are sensitive.”

She highlights an example from Myanmar: In the “Open History ProjectExternal link“, which is funded by the German government and implemented by Helvetas, people are asked to explore different interpretations of their country’s history.

While organising the exhibition and producing video interviews for the project, people from different ethnic groups talk to each other and share differing viewpoints. Gattiker explains that, “in this way, the project helps promote peace in a country that has more than 130 ethnic groups”.

Peace-building through art

Helvetas has integrated its cultural projects into programmes for peace promotion, conflict prevention and rule of law – key goals in Switzerland’s development cooperation strategy for 2021 to 2024.

“Arts and cultural projects greatly contribute to our goals,” the SDC explained in a written response . “Cultural projects can be used to create understanding and tolerance and be a step towards returning to hope and normalcy after conflicts.”

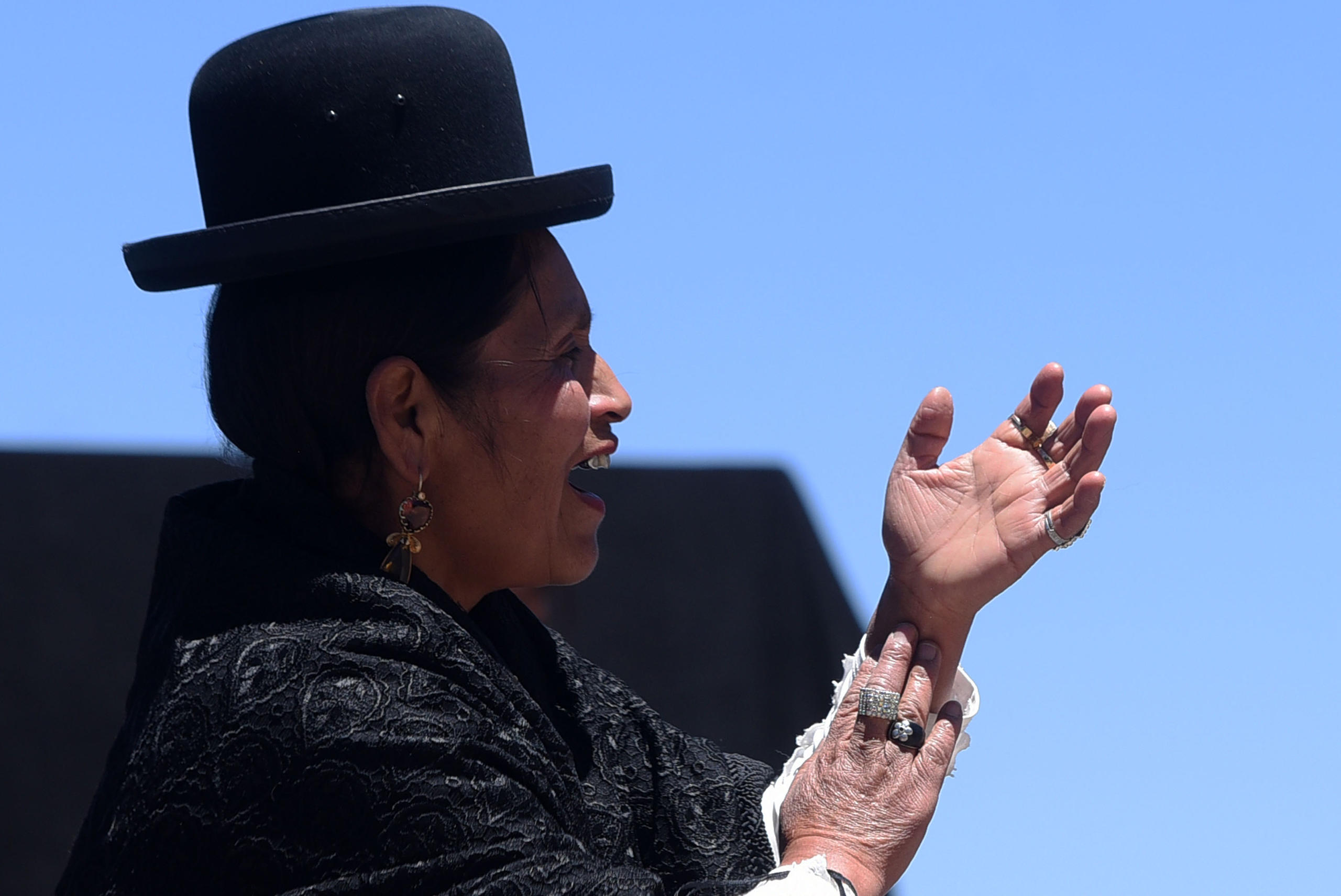

The SDC, a division of the Swiss foreign ministry, funds cultural programmes to the tune of CHF4-6 million ($4-6 million) annually. In Afghanistan, for example, these funds support local arts initiatives to strengthen social cohesion, while in Bolivia, support for local cultural projects addresses violence against women and human rights. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, these funds help bring young people together to play rock music in the divided city of Mostar.

“In regions where so-called frozen conflicts prevail, cultural programmes are often the only development projects that can be implemented,” says Dagmar Reichert, director of artasfoundationExternal link – the Swiss Foundation for Art in Regions of Conflict. The Zurich-based organisation, which was established in 2011, works outside big cities and close to conflict zones. One-fifth of its CHF280,000 annual budget is funded by the SDC.

For the past few years, artasfoundation has been implementing projects in the South Caucasus region of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan where a protracted crisis persists in the regions of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno Karabakh.

“Nothing really moves in this conflict, and the population does not have the power to change anything,” says Reichert. “Cultural programmes give people, in particular young people who feel excluded and isolated, the opportunity to open up and meet others.”

“In regions riddled by conflict with no perspectives, cultural projects can contribute to the fight against fundamentalism,” says Reichert. “Several studies show that young people turn to fundamentalist organisations because they give them value and a purpose.”

Reichert is convinced that young people, particularly those living in remote areas and refugees in crisis and conflict regions, would be the losers if the budget for culture promotion were cut. “People want to be seen as more than just bodies that need to be fed and protected. They have lost a lot, but nobody can take their culture away from them.”

Consultations on the future of international cooperation

A draft of the “Explanatory Report on International Cooperation 2021-2024External link” has been available for public consultation since May 2. This is the first time that civil society actors, political parties, and the general public have been able to voice their views on the strategic and conceptual focus of Swiss development cooperation.

Prior to the release of the report, the Federal Council (executive branch) determined the key focus areas, namely the needs of the people in partner countries; the promotion of Swiss interests on economic matters, migration and security, and areas where Switzerland can add particular value.

The Federal Council has assured that the proposed approach will keep poverty reduction and human security as strategic goals. At the same time, however, it places more emphasis on economic aspects such as working with the private sector and strengthening alignment between migration policy and international cooperation. It also intends to focus on four geographic areas and withdraw its aid from Latin America after 60 years in the region.

The report is available on the Federal Council’s website until August 23 and parliament is expected to make a decision in February 2020.

Adapted from German by Billi Bierling

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.