Is the Swiss People’s Party far-right?

The foreign press does not hesitate to describe the Swiss People’s Party as far-right, while the Swiss media prefers the terms conservative, populist or nationalist right. Political scientist Oscar Mazzoleni explains why the extremist label does not fully reflect the party’s position in the Swiss political landscape.

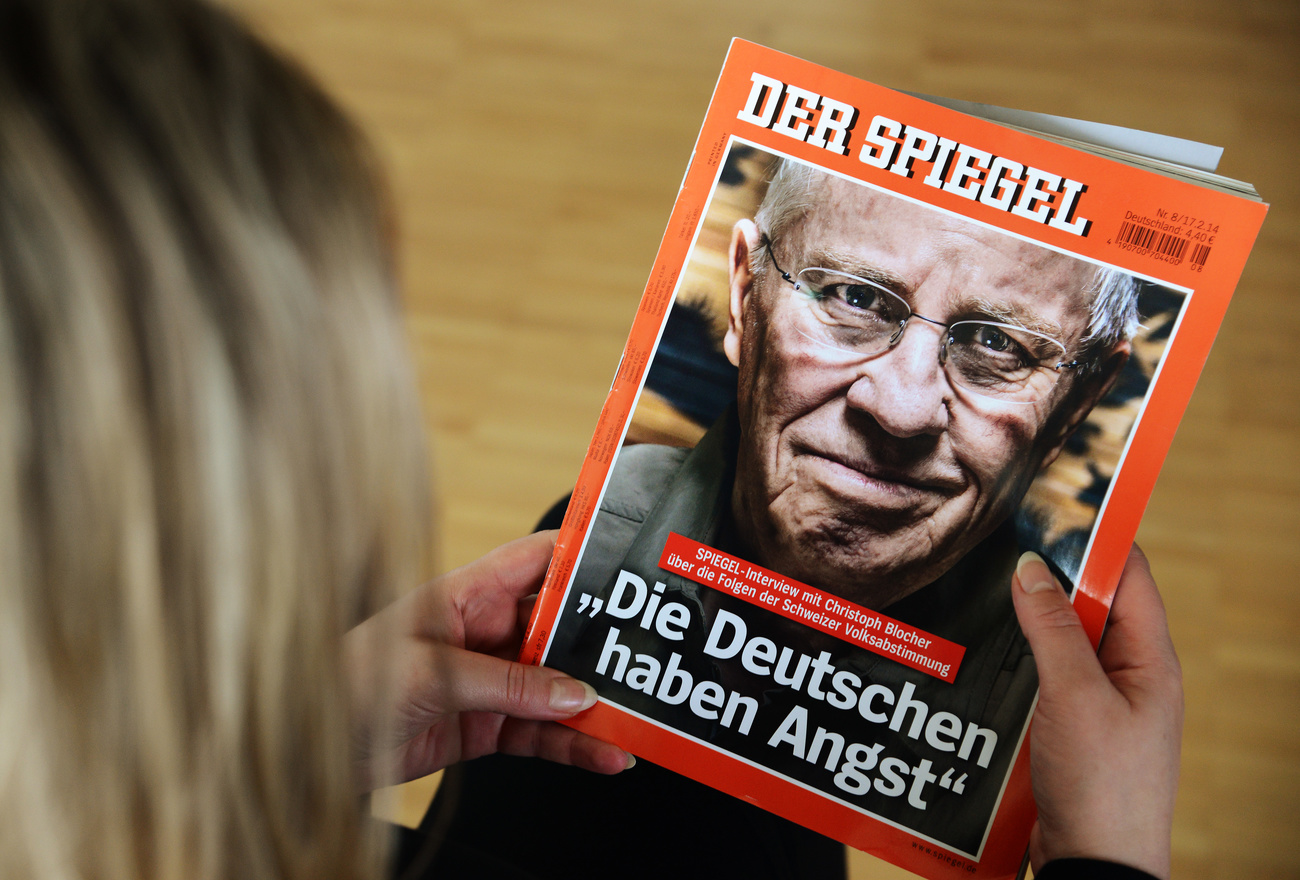

The victory of the Swiss People’s Party in last month’s federal elections has rekindled debate on the political orientation of the country’s leading party. On the French news website MediapartExternal link, Swiss historian Charles Heimberg recently wrote that the People’s Party “has become a far-right party through its positions and campaigns”. The German newspaper FocusExternal link also declared that the big winner of the federal elections was “the far-right People’s Party”.

These statements did not fail to provoke reactions in the Swiss press, which does not use the term far-right to describe the country’s largest party. An editorial published on the news site watson.chExternal link asserted that it was time to stop making an exception for the People’s Party. “Either this party is defined as far-right, like the Rassemblement National in France and the Brothers of Italy, or none of these groups should be so termed,” it wrote.

More

Elections 2023: Swiss parliament shifts to the right

Other newspapers, such as Le TempsExternal link, noted that the party “is part of many cantonal executives as well as the federal government” and that “the elected representatives respect the institutions”, concluding that it is not a far-right party.

Oscar Mazzoleni, professor of political science at the University of Lausanne and author of several books on the political organisation of the conservative right, also believes that the People’s Party is different from other European parties that are classified as far-right.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Unlike the Swiss media, the foreign press does not hesitate to call the People’s Party a far-right party. Isn’t this an oversimplified exaggeration?

Oscar Mazzoleni: The foreign press focused on certain aspects of the election campaign, in particular the issue of immigration. Many European countries have parties that express similar views to the People’s Party on this question and which are often referred to as far-right. It is therefore understandable that some parts of the media use the same categories.

However, the People’s Party is not just about certain campaign arguments and immigration. It has an economic agenda that is very close to the traditional right and it has participated in collegial and multi-party executives at various levels for decades. The far-right label does not capture the complexity of the party, nor its enduring success.

SWI: What criteria determine whether a party is far-right?

O.M.: There is a fundamental ambivalence about the term far-right that makes it hard to handle. In the ideological sense, it is used to describe forces that are close to or heirs of the fascist or Nazi tradition. In German, it refers to anti-democratic forces. However, the term also has a more neutral connotation, used to designate the party that is furthest to the right on the political spectrum.

More

Outrage over tweet by People’s Party member

SWI: So how would you define the Swiss People’s Party?

O.M.: I don’t have a simple answer. The People’s Party is a conservative party on the political right, a nationalist party, a populist party, depending on the situation or the moment. A single label does not give a full picture of the complex place that this party occupies in the Swiss political system. It is both a government party and an anti-establishment party.

SWI: The Alternative for Germany, the Rassemblement National in France and the League (Lega) in Italy are classified as far-right. How do they differ from the People’s Party?

O.M.: The case of Alternative for Germany is simple. It is an opposition party with its roots in the Nazi heritage. The Rassemblement National in France is the heir to the National Front, founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen, who was convicted several times for anti-Semitism, and by a former member of the Waffen SS. It is also an opposition party that has never been in national government and is in the minority at various levels of the French political system.

The People’s Party, meanwhile, is both inside and outside the system, in particular because of the referendum system that enables it regularly to stand out from the other main parties on the issues of immigration and Europe.

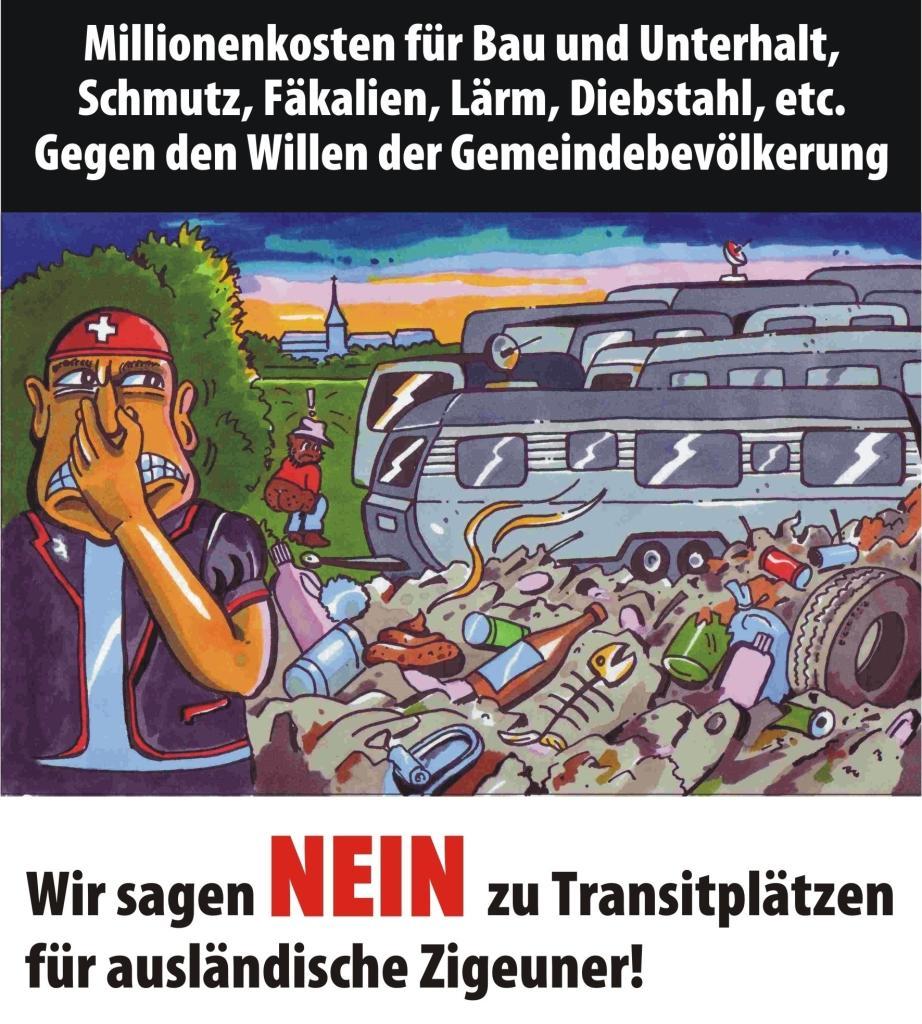

SWI: Nevertheless, some anti-racist associations have filed criminal charges against the People’s Party for the visuals used during its election campaign. Do they have a chance of succeeding?

O.M.: This will depend on how the judges interpret the criminal anti-racism legislation. But this is nothing new. For the People’s Party, provoking scandal is seen as a campaign resource. It’s a way of attracting attention, being spectacular and doing political marketing.

SWI: Thomas Stettler, a People’s Party parliamentarian from the Jura region, recently described himself as xenophobic on live television. Has the party made xenophobia acceptable in Swiss political debate?

O.M.: For the past 30 years or so the People’s Party has been trying to push back the limits of what is acceptable in public opinion and debate regarding immigration and foreigners. We saw this in 2007 with the campaign depicting white sheep kicking a black sheep out of Switzerland.

More

People’s Party becomes political black sheep

SWI: Apart from the Greens, the other parties barely attacked the People’s Party for its anti-immigration campaign and rhetoric. How do you explain this?

O.M.: This time, the other parties didn’t want to give too much visibility to the People’s Party, because that’s exactly what it wants. They reacted a lot to this kind of campaign in the past, before realising that this drew even more attention to the People’s Party.

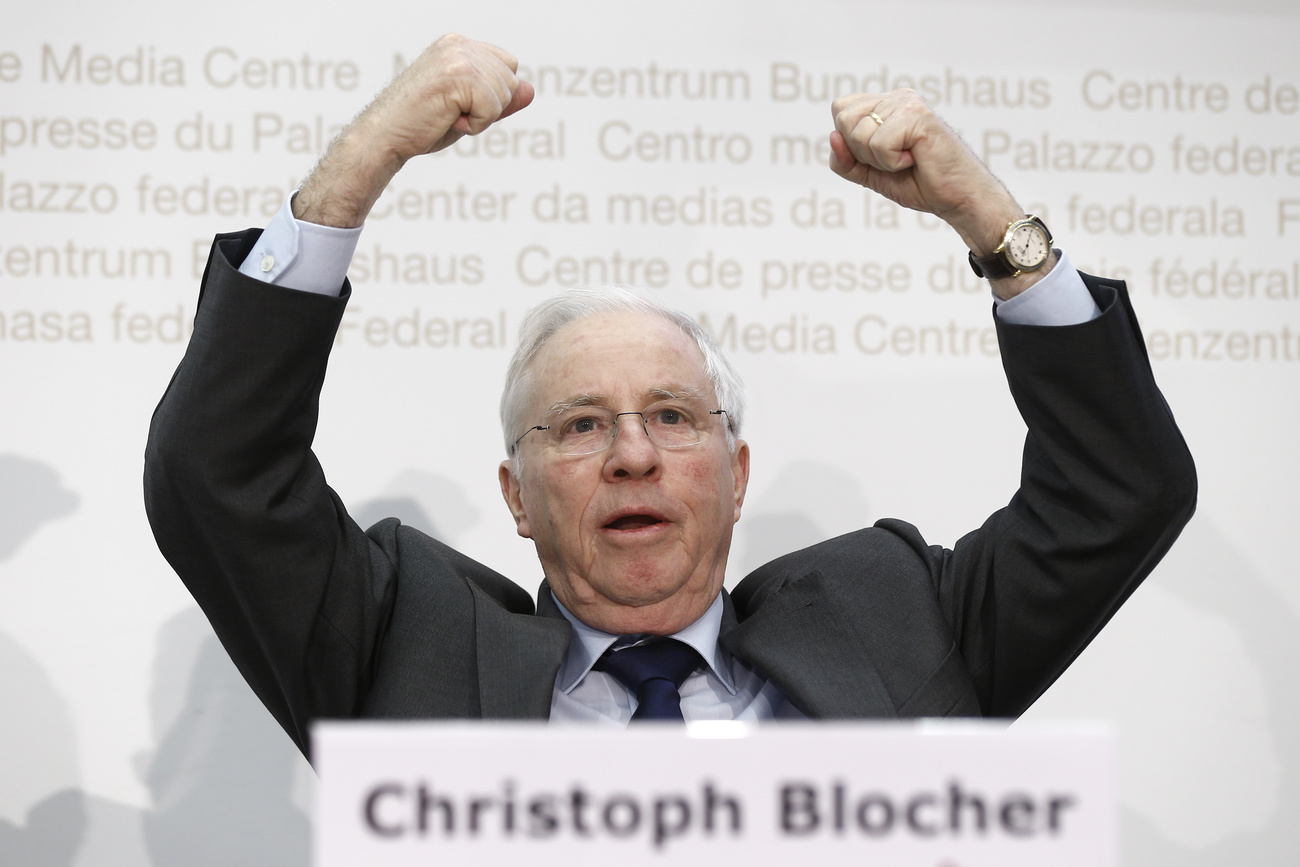

SWI: Christoph Blocher gave the People’s Party a new direction in the 1990s. Will this line outlive him?

O.M.: Christoph Blocher reshaped the party fundamentally in the 1990s. His political line was instrumental in the creation of new cantonal and local sections. He also played a key role in grooming the next generation. He pushed people to the party’s helm who are still there today. As the party continues to score major electoral successes based on his political line, Blocher’s legacy will undoubtedly live on.

SWI: The victory of the People’s Party in the federal elections has brought 11 more farmers into parliament. Does this signal a return to an agrarian and therefore more moderate tradition in the party’s politics?

O.M.: The People’s Party underwent an overhaul, but it never denied its rural tradition. Besides, it has never changed its name since it was founded in 1971. Even though the party has shifted towards economic neo-liberalism, it has never questioned agricultural subsidies. The farming sector continues to be central to its programme, as a pillar of a certain vision of Switzerland. It should also be noted that the farmers elected to parliament do not correspond to a bucolic vision of agriculture, but are often businessmen who run farming companies.

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Translated from French by Julia Bassam.

More

Young Swiss politicians convicted for ‘gypsy’ poster

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.