Luck with lists and misfortune with proportional representation

Switzerland’s electoral system favours large political parties at the expense of small ones. The list combination counteracts this, as demonstrated by a visual analysis by the online service of Swiss public television and radio, SRF. Parties to the left in particular benefited in recent election years. However, change is on the horizon.

In 2011, the Swiss People’s Party suffered a historic setback in elections for the House of Representatives. In contrast to the 2007 elections, the People’s Party lost 2.3% of the vote.

Even more devastating was the loss of eight seats due to list combinations. If that system had not existed, the People’s Party would have won 62 seats – the same number as in the previous election – rather than the 54 it ended up with.

Other parties benefited from the list combinations, with the Liberal Green Party adding five seats thanks to the system, while both the Christian Democratic Party and the Social Democrats picked up two seats each.

Distortion favours the largest parties

The switching of seats in 2011 highlighted a peculiarity of the Swiss electoral system. The People’s Party would have captured 31% of the seats in the House of Representatives with just 26.6% of the vote without the list combinations.

In contrast, the Liberal Greens would have only been awarded 4% of seats despite receiving 5.4% of the vote. The reason for this distortion is the procedure that distributes seats to the various parties in each canton.

“Similar to a poll tax, a fixed rate is deducted from the mandates that should be awarded to each party,” explains Daniel Bochsler, a political scientist at the Zurich University and the Centre for Democracy Studies Aarau. “This poll tax is chiefly awarded to the big parties.”

The allocation process thus distorts proportional representation at the expense of the small parties.

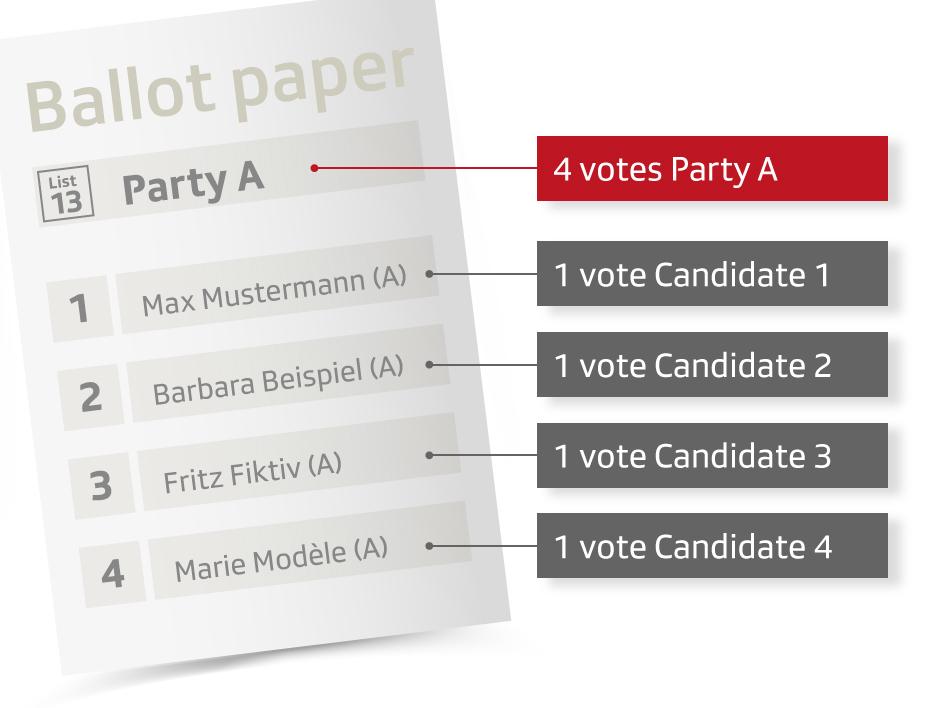

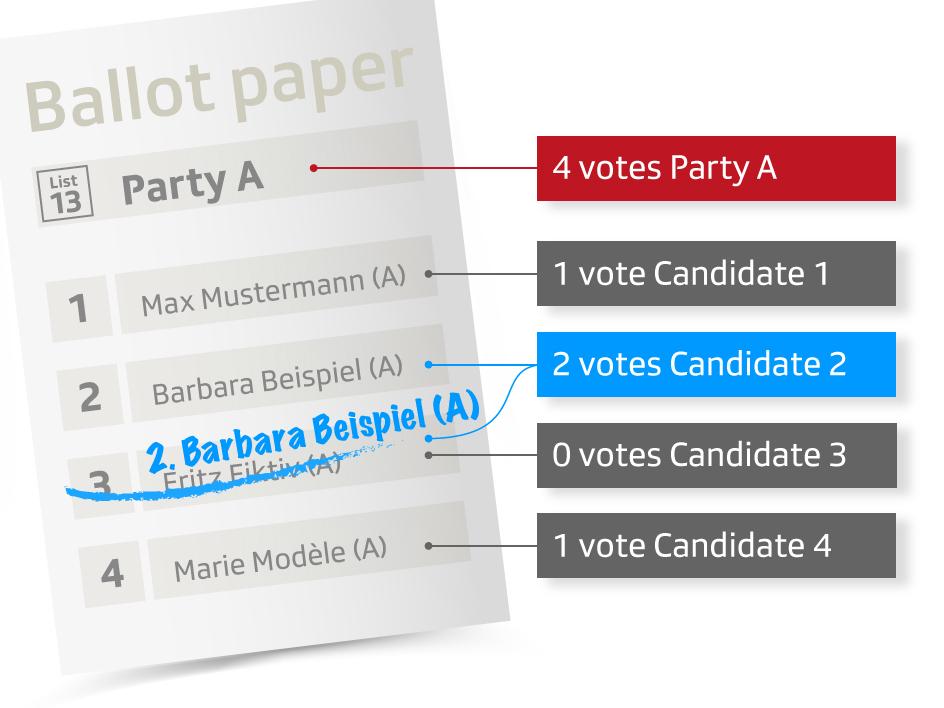

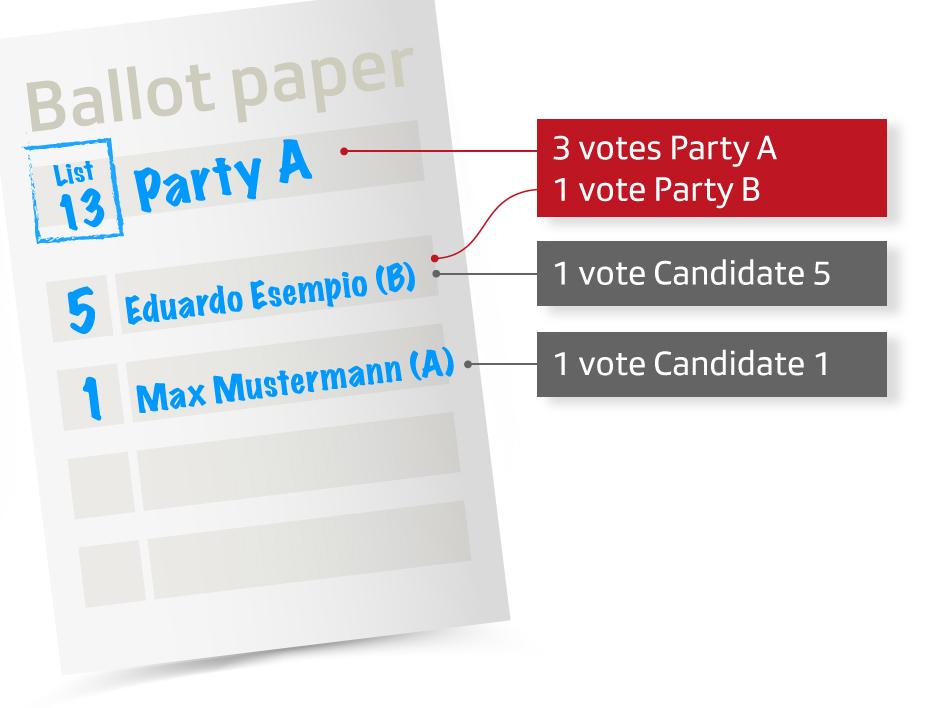

List combinations are supposed to correct this. They allow for combinations that create an ostensibly larger party that has better chances of winning a seat. This allows small parties in particular to counteract the distortion. Within a list combination, though, the party with the most votes tends to win, according to Bochsler.

A review of historic wins and losses

Indeed, only two of 12 cases during 2011 were different. In canton Graubünden, for example, the Liberal Greens won an extra seat because it was linked with the much stronger Social Democratic and the Green Party. This again was at the expense of the People’s Party, which would have had one more seat in purely mathematical terms if list combinations were not possible.

A visualisation by SRF shows which configurations during the past five elections resulted in wins or losses.

Bochsler calculated the seat losses/gains as a result of list combinations during the past five elections. His analysis demonstrates that there are a few moderate winners, along with two big losers.

The latter are the People’s People, which has lost 19 seats since 1995, followed by the Radical Party with 11 lost seats.

This is in contrast to the Green Party, for example, who captured a total of eight additional seats thanks to their skillful manoeuvres.

A return to centre-right list combinations

Over the past 20 years, the left-green parties have generally benefited the most from list combinations, Bochsler explains. While they were indeed more fragmented than the centre-right parties, they were able to retain a common political line.

The list combinations enabled them to pay the proportional system’s “poll tax” just once for the “entire family”. The emergence of new, centre-right parties, however, signals change on the horizon.

The Radicals and Christian Democrats lost a large number of voters to the Conservative Democratic Party and Liberal Greens in 2011. It’s more worthwhile than ever for them to link up together.

List combinations: pig in the poke?

However, collaboration with the party that has the most votes, the People’s Party, remains unrealistic. Voters would hardly approve of such a move, Bochsler believes, referring to panachage statistics and surveys. On this account, list combinations tend to follow political views.

The problem is this: often voters are not even aware of the fact that by casting a ballot, they may be helping another party gain a seat.

That’s because list combinations are usually only indicated at the edge of a ballot. Finding out who are the partners to a list combination proves to be a tedious task.

One example of an unusual combination occurred in the canton of Thurgau during the 2011 elections: Federal Democratic Union and Protestant Party voters helped the Liberal Green Party capture an additional seat.

Consistent, national rules and improved identification of list combinations by using colours, for example, would lead to greater transparency. For the upcoming elections in October, however, there is no improvement in sight.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.