Millennium Goals: all talk, no action?

Later this month in New York, the United Nations General Assembly is set to start addressing an ambitious new sustainable development proposal that aims to build on the work that began with the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

A series of new sustainable development goalsExternal link will replace the MDGsExternal link, which will expire in September 2015. But how much has actually been achieved since 2000, when 189 UN member states declared their intention to combat global poverty by signing the non-binding Millennium DeclarationExternal link? swissinfo.ch sought answers from three specialists in economic development.

“The MDGs pushed governments and civil societies around the world to engage on behalf of a catalogue of important social priorities,” says Nina Schneider, consultant and former director of development policy at Alliance SudExternal link, a coalition of Swiss non-government organisations. “Measurable objectives and time limits (2015) helped to improve actions aimed at fighting poverty.”

It is important too, to recall the context in which the UN initiative was developed, says Jean-Michel Servet, development economist at the Geneva Graduate InstituteExternal link.

“During the 1990s, development was largely founded on neoliberal policies [the Washington Consensus],” says Servet. “We realised that the attribution of development aid founded on these principles had catastrophic effects in terms of increasing poverty. The MDG woke people up to the fact that the markets alone could not resolve all the problems linked to poverty.”

So the question must be asked: have the UN and its member states succeeded, via the mechanism of the MDG, in reversing the trend and improving the lives of those stricken by poverty around the world? Nothing is less certain.

The first of the MDGs was to reduce the rate of extreme poverty by half. Released in July, the 2014 UN progress reportExternal link into the achievements of the MDG notes that global poverty “has been halved five years ahead of the 2015 timeframe”.

More

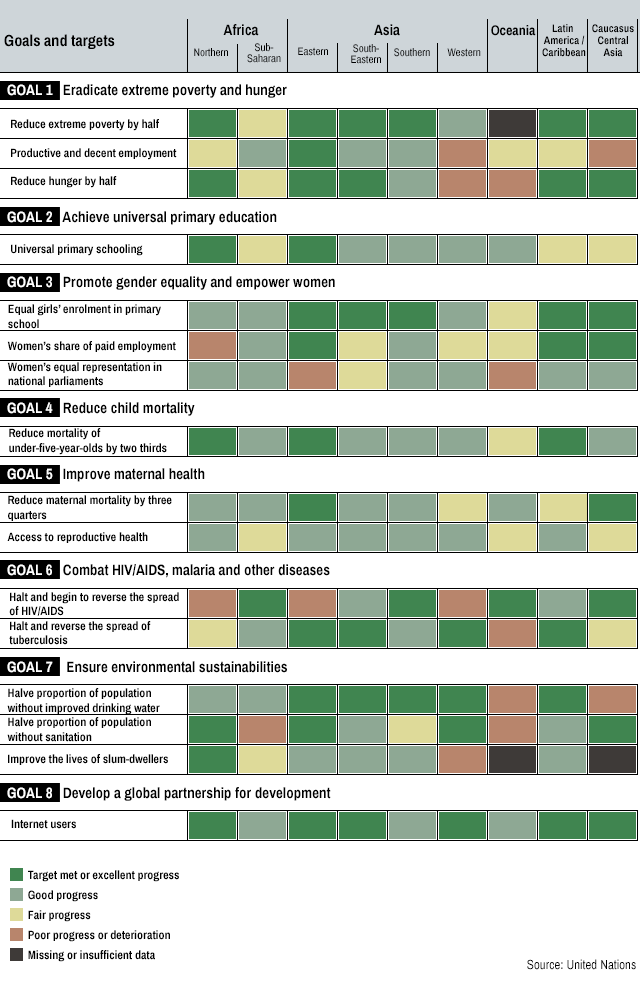

MDG 2015 progress chart

However, Schneider says this has been achieved less as a result of the MDG and more as a result of China’s booming economic growth over the last two decades. Jean-Louis Arcand, professor at the Graduate Institute Geneva,External link is also sceptical as to how much success can be attributed to the MDGs, which he describes as a “wish list” that crucially, does not mention problems of inequality and redistribution of wealth.

“Take for example the World BankExternal link’s definition of extreme poverty which is those people who are living on $1.25 per day. It means we focus on those who earn less than that amount, but what about those who earn $1.80, or a bit more? There is a tendency to focus on categories based on one characteristic, when the situation is a lot more complex,” he says. “For a programme that fights poverty to work, you have to include the middle classes, and you have to do this so that they do not paralyse the programme as we have seen happen in Argentina.”

The development of MDGs was stymied by economic policies such as deregulation of international trade rules and global financial markets that dominated thinking in industrialised countries during the 1990s, according to Schneider.

“This killed the development of many poor countries, plunged the world into the worst economic crisis since the 1930s and pushed us to the ecological limits of our planet,” she says.

Servet agrees: “What nobody wanted to look at is that poverty is fundamentally determined by inequality and discrimination,” he says. “If we don’t fight discrimination itself, poverty simply reproduces.”

The laboured internal workings of the UN itself are also responsible for perverting good intentions and lessening the impact of such worthy goals, argues Arcand.

“When they fix these objectives in the conference rooms of New York or Geneva, it sometimes creates completely perverted incentives,” he says. “We focus on some goals for political or other reasons, and neglect others. The very narrowness of the fixed goals can pervert the implementation of various programmes.”

Limits to aid

While noting that much remains to be done, the UN can and does boast a number of achievements in sustainable development.

“Ninety per cent of children in developing regions now enjoy primary education, and disparities between girls and boys in enrolment have narrowed,” says UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon in the 2014 MDG report. “Remarkable gains have also been made in the fight against malaria and tuberculosis, along with improvements in all health indicators.”

Yet Arcand remains unconvinced, arguing that development aid money does not create economic growth.

“No country in the world has lifted itself out of poverty because of the development aid programs financed by the World Bank or the European Union,” he says. “The countries that have succeeded are those that have a solid institutional environment and private sector.”

A major financial contributor to development programmes, the World Bank and its regional branches are heavily involved in the choice, financing and evaluation of development of MDG programmes, says Schneider.

“They are able to sanction countries which refuse to implement their measures and principles,” she says. “But they contribute little to a fair sharing of the burden at an international level, or to tax, financial or commercial.”

Financial problems

The massive influence of global financial players has also had a key impact on the ability to resolve problems of poverty and development, says Servet, who argues that without a “return to a certain level of taxation”, it is difficult to see how MDGs can be achieved.

“[Financial players] all act so that taxes will be at a minimum,” he says. “It is not the market that produces democracy, but taxation, which is decided on by the parliamentary assemblies. How can you develop democracy if you weaken the state by diminishing the tax take?”

In addition, many countries that typically finance development programmes are not inclined to increase their contributions. This fact threatens to throw a shadow over negotiations for a new set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)External link which are set to be adopted at a summit of heads of states in September 2015.

“The real economic power lies with the multinationals,” says Arcand. “But the UN holds power over them in terms of their social responsibility. What is essential is the capacity of countries to establish a strong and conducive institutional environment.”

For her part, Schneider is hopeful that the SDGs will lead to more positive outcomes than the MDGs.

“A global agenda for development post-2015, that takes into account the social disparities and limits of the planet, offers a unique chance to go beyond the deficiencies of the MDGs,” she says. “The agenda should be founded as much on recognised international human rights as well as the principles of Rio 1992. Without such an agenda, the world will move towards growing social and ecological destruction, the societal consequences of which will only be difficult to manage politically.”

During the 69th session of the United Nations General Assembly External linkwhich opens in New York on September 16, a working group will meet to discuss negotiations for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This new catalogue of measures is to be adopted during a global summit at the following general assembly of the UN in September 2015.

Established in 2012, the working group is made up of representatives from 30 countries. Switzerland shares a seat with Germany and France.

Source: United Nations

(Adapted from French by Sophie Douez)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.