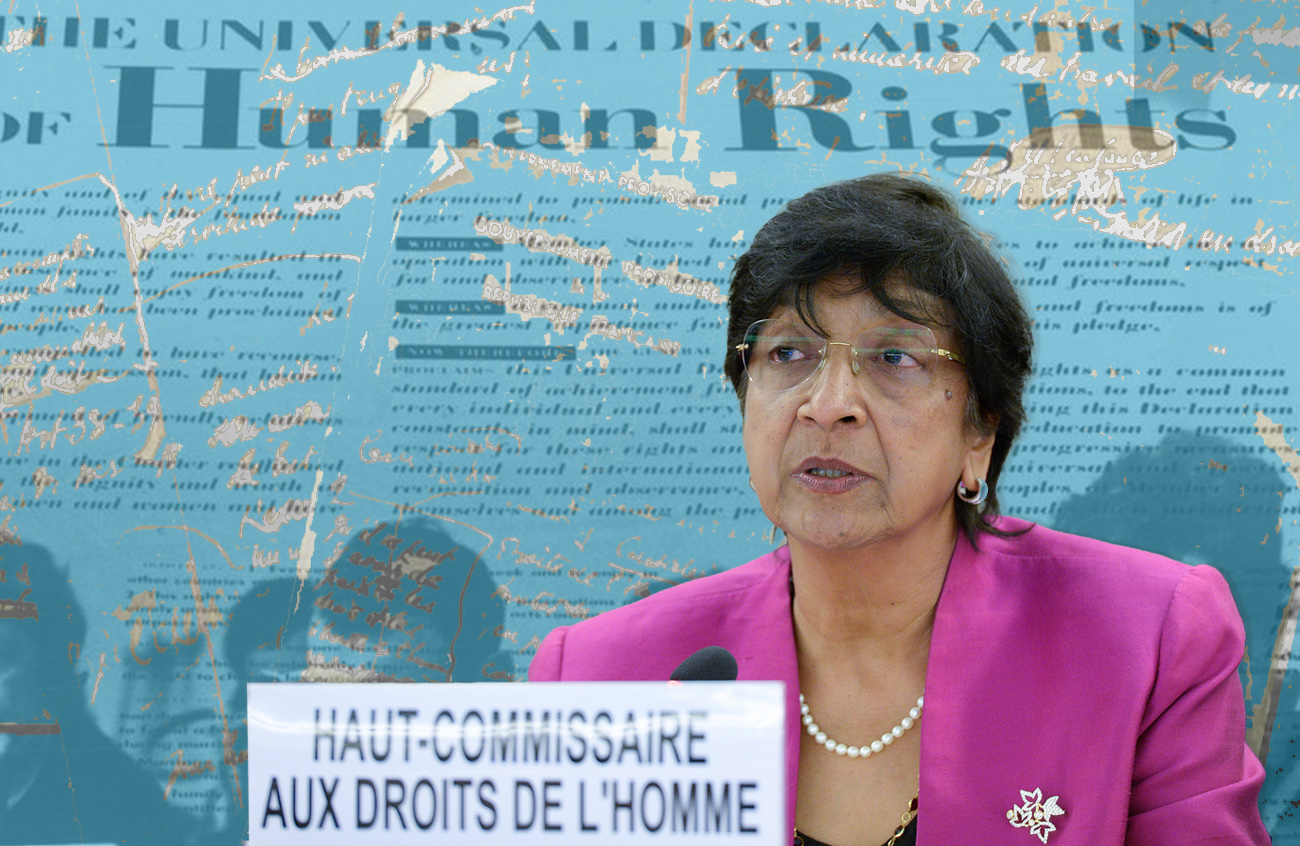

Navi Pillay: an intrepid fighter for rights and equality

She grew up in apartheid South Africa, became a lawyer who helped get more rights for political prisoners including Nelson Mandela, and was the first non-white woman judge on South Africa’s High Court.

Throughout 2023, SWI swissinfo.ch has been marking the 75th anniversary of the universal declaration of human rights, a ground-breaking set of principles and also – fun fact – the most translated document in the world. The current UN human rights commissioner, Volker Türk, describes the declaration as “a transformative document…in response to cataclysmic events during the Second World War.”

The very first commissioner, Jose Ayala Lasso from Ecuador, took office in 1994 – why so late when the universal declaration was drafted in 1948?

Our Inside Geneva podcast has interviewed all the former UN Human Rights Commissioners (a job sometimes called the UN’s toughest) to hear their experiences, their successes, and their challenges.

As a judge at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, she helped get rape recognised as a component of genocide. Navanethem Pillay was also the only High Commissioner for Human Rights to get two mandates (2008-2014). We talked to her about what it was like in the UN’s toughest job.

Born of Indian Tamil origin in Durban, South Africa, in 1941, “Navi”, as she likes to be called, was clearly marked by growing up in a racist society. “Even as a six-year-old, when my parents said ‘no, we can’t go to that beach, it’s for whites only, no you cannot play on those swings, that park is for whites only’, I thought what kind of law is that? It’s not fair!” she tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

So the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was something that meant a lot to her and other human rights activists in apartheid South Africa. Later as High Commissioner she became the guardian, in a sense, of that landmark declaration adopted by the UN in 1948. And she agrees it is a very challenging post.

She says the Universal Declaration and the Conventions that came out of it were the result of a civil society push and did not come from states themselves. Although they have all signed up to it, they do not necessarily respect their obligations.

“Why is so much effort needed from civil society or people on the street and UN mechanisms to get them to adhere to the international standards that they claim to support?” she asks. “That’s what I see as the biggest challenge.”

Social media and Syria

Pillay remembers how she took the post amid the rise of social media. One of the High Commissioner’s key jobs is to identify human rights needs and make statements about them, she tells SWI. At the time, this was done by trying to get op-eds in big newspapers like the New York Times, which might or might not publish, or sometimes hide them on a back page.

“But with social media, the statements I made as High Commissioner instantly went around the world. To me, that was so miraculous,” she says. “Being older generation, it was just incredible when my office monitored these messages and said to me ‘the message you put out yesterday is now being read by two million people’. It was said that those were the golden years for human rights.”

She was High Commissioner for Human Rights at the time of the Arab Spring and the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011. That was tough, she recalls. “The challenge for me was to call for a ‘no fly zone’ to protect civilians from the aerial attacks launched by Bashar al-Assad [president of Syria since 2000]. I was responding to pleas from civil society and investigations by OHCHR [UN human rights office]. I made this call in Brussels before EU representatives and learned from them that it would involve a military exercise.”

She says she was deeply troubled by the massive warfare that followed – between Al-Assad’s forces backed by Russia, and coalition forces – which led to massive destruction and displacement of people in a conflict that still has no end in sight. “I grieved that I may have unintentionally contributed to the disastrous outcome by calling for protection against bombing of Syrians in the first place,” she tells SWI.

Fighting for equal rights

Pillay stresses that the work at her UN office in Geneva was not just the efforts of one individual but a whole skilled and dedicated team. But she is proud particularly of what she did to fight discrimination, for example on LGBTI rights.

“I was the High Commissioner who put that issue on the agenda of the Human Rights Council, and then it went before the General Assembly, and subsequently there was lots of discussion, a great deal of assistance from various parts of the world, North and South.”

The other issue of which she is very proud, she says, is caste. India had successfully managed to keep this off the UN agenda for decades. “When I initiated a conference in Geneva on that issue, and had panels from all over the world, I was able to say to India, it’s not only you: caste discrimination occurs in all these other countries. We had people from the islands outside Japan, we had people from Mauritania with slavery still being practised there, and from Nepal.”

She had to be diplomatic. “The Indian ambassador said to me, caste is a word peculiar to India, it makes sense only in India and you shouldn’t use it. That’s why we don’t want it discussed at an international forum,” Pillay says. “I replied that he should be generous and lend the word to the world exactly as South Africa has contributed the word apartheid to the international discourse.”

Being High Commissioner was very different from her previous job as a judge. “You know, we were judgmental, we sentenced people. But to be a High Commissioner, you have to be an advocate, to find the right argument and approach and offer help in order to get advancement of human rights protection,” she says.

‘Wrong structure’

As High Commissioner, what she liked best was “when the message got through”. But there were also things she hated about the job. “I think it’s a wrong structure to have one person sitting at the top of the pyramid and everybody wants to see that one person, whether it’s ministers from various countries, the staff, civil society,” says Pillay. “And it became just overwhelming. I was doing meetings every 15 minutes, it even ate up my lunch time.”

As a lawyer and judge, she had enjoyed independence and “time to think”, and “wasn’t crowded all the time”. Before taking the High Commissioner post, she says she sounded out her predecessor Louise Arbour who also said lack of time was her main concern “and I told her I will control my own schedule”. But, once in post, Pillay says she “failed hopelessly” to do that.

At 81, Navanethem Pillay is still active on human rights. She currently chairs the Independent Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian TerritoryExternal link, set up by the Geneva-based UN Human Rights Council in 2021.

Edited by Imogen Foulkes

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.