Outbreak of war revealed divisions among the Swiss

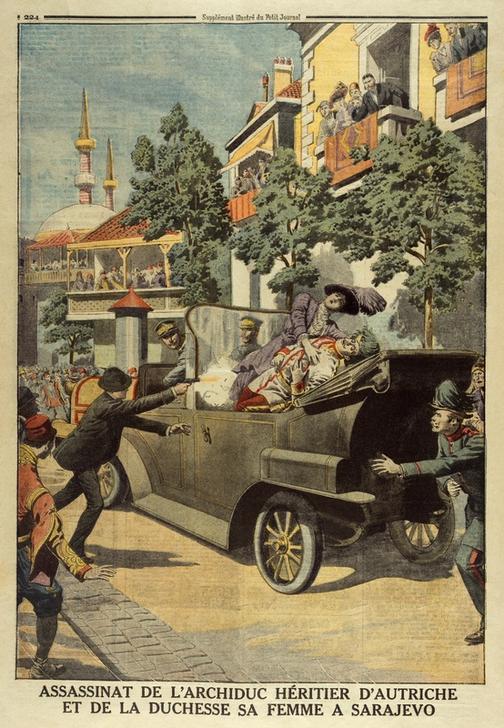

One hundred years ago, in an attack that would spark the bloodiest war the world had ever seen, Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip assassinated Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. Swiss press reports of the events reveal the deep divisions within the country at the time.

Heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand was shot and killed along with his wife on June 28, 1914. The most foresighted among the Swiss press warned from the beginning that the killings would provoke unimaginable consequences.

“It is one of those events which turns everything on its head, cancelling conjecture in an instant, wiping out imagined deadlines, and giving rise to agonising questions that nobody has contemplated,” wrote the Tribune de Genève.

Wave of sympathy

Initially, the attack gave rise to a wave of sympathy for Austria-Hungary and in particular for its emperor Franz Joseph, uncle to Franz Ferdinand.

“All our sympathies go to the venerable emperor. His life, already so tragic, was again darkened on Sunday by yet another tragedy,” wrote the Tribune de Genève, referring to the family dramas which had marked the life of the king, notably the assassination in 1898 in Geneva of his wife Elisabeth (‘Sissi’) and the suicide of his son Rudolph.

The death of Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, who had, unusually, married for love and left three orphaned children, also moved journalists. Even the Berner Tagwacht, official mouthpiece of the now centre-left Social Democratic Party and little inclined to show pity to royalty, expressed compassion.

But aside from the immediate drama, opinions diverged about the heir to the throne. The Catholic press launched a real outburst of praise, whereas the Berner Tagwacht was much more critical. For the social democrats, Franz Ferdinand was “the incarnation of this Austrian policy which is driving its people to the edge of the precipice” and “represents militarism, imperialism and clericalism”.

But most commentators viewed the heir to the throne as actually being a friend of the Slavs.

“Far from wishing that the people of the realm be oppressed by another, Franz Ferdinand was a determined supporter of national emancipation. Princip slanders his victim by saying he killed a Serbian oppressor; he put to death someone feared by the Serbs precisely because he saw that he could attach the Slavs to the monarchy through ties of the heart,” opined the Catholic paper La Liberté.

A similar view was expressed in the “liberal” press.

“The aberration of the attack reveals itself in the fact that Archduke Franz Ferdinand was rightly considered a friend of the Slavs; one could claim that he would be satisfied with the idea of a third state (alongside Austria and Hungary) within the monarchy,” wrote the German-speaking Der Bund.

A Swiss gulf

During the four weeks which followed the assassinations, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire piled the pressure on its Serbian neighbour, to the point of launching an ultimatum in a letter dated July 23. From that point, given the game of alliances, the spectre of war seemed inevitable. But the Swiss press was again divided as to who was the real instigator of war.

The division was commentated thus in Geneva’s La Suisse: “While elsewhere public opinion has hardened in one direction or the other, our press presents to the world the spectre of a divergence of opinions which reveals a total lack of direction.”

The Catholic press unwaveringly supported the Austrian policy. “Austria-Hungary conducted an inquiry and made conclusions as to the threat it faced; she is not going to wait one more minute to deal with it,” wrote La Liberté.

Pro-Austrian sentiment was also strongly linked to a consistent hostility towards Russia.

“If the general uproar occurs, the fault will lie with Russia because it is not her place as a nation to intervene in the Austrian-Serbian dispute. Its links to Serbia are only those created by a schismatic religion, it is prejudiced by default and should stay quiet,” wrote the Catholic daily from Fribourg.

“The Russian government has gone to the absolute limit of what the desire to avoid war allows a big nation to do,” wrote the Tribune de Genève in contrast.

The alignment of the Catholics with the Austrian position scandalised the socialists. “If we pick up a Catholic newspaper it is actually difficult to tell whether or not it is still a republican paper,” derided the Berner Tagwacht.

More

War widens cultural divide in Switzerland

It is worth noting, however, that religious and political alliances were not the only considerations. The cultural proximity to large neighbouring countries also played a role. Throughout the conflict, a gulf divided Switzerland: the French- and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland were close to the Allies but the German-speaking half was vocal in its support for the central powers

The Italian-speaking Corriere del Ticino, closely affiliated with the Catholic Church, was much more critical of Austria – a sign of the sympathies of the Italian-speaking canton towards the Italian irredentism – wanting back the regions with Italian minorities in the Austrian Empire.

“Let’s remember that Austrian policies towards Serbia have always been policies of oppression and repression,” noted the paper, for which Serbian propaganda was “a natural reaction to a police repression compared to which the repression of Italian-speakers at Trieste was nothing”.

Master of the hour

Among the papers on the more “liberal”side of the fence, opinions were more divided. But the general tendency was to blame Austria for the outbreak of the conflict.

“If the catastrophe that we suspect is coming arrives, Austria-Hungary, its king, its government, its military party and especially those who employed themselves with a detestable ardour in provoking the current conflict, will bear the entirety of responsibility,” wrote La Suisse.

This opinion was shared in the German-speaking part of the country.

“The fact that in its letter Austria did not declare itself at least open to new negotiations shows that it wanted war,” wrote the Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

The position of Germany and its emperor Wilhelm II remained for comment. For the Tribune de Genève “the future of Europe and of civilisation is in his hands”.

For its part, La Suisse wrote: “In these stormy hours, the entire world has its eyes turned to the ruler who appears to be the master of the hour, and from whom an energetic gesture would be enough to appease passions, put an end to the excesses of the Austrian military party and to stop the amassing of arms that is occurring at fever pitch from the shores of the Atlantic to the borders of Asia.”

But the “energetic gesture” would never come…

Game of alliances

In 1914 two main alliances existed: the Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy and the Triple Entente of Britain, France and Russia. The game of alliances transformed what started as a local conflict between Austria and Serbia into a European, and then a global conflict.

In the first instance, Russia supported Serbia, while Germany sided with Austria. Next, France intervened because of its military alliance with Russia. Initially on the sidelines, Britain became involved in the conflict when Germany violated Belgium’s neutrality to invade French territory.

Italy stayed neutral before joining the Triple Entente in 1915 to take back the Italian minorities from the Austrian empire (Trieste and South Tyrol). Among the big powers, the Ottoman Empire joined the central powers in 1915 and the United States lined up with the Allies in 1917.

(Translated from French by Sophie Douez)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.