Organ donation: direct democracy and the law

Every adult who dies should automatically become an organ donor: that’s the idea behind a Swiss people’s initiative. However, two doctors who have increased the number of donations in canton Ticino describe the scheme as a dangerous shortcut.

“But where’s his soul now?” “We agree in principle with donating the organs of our loved one, but that would turn him into a giraffe in his next life; therefore we can’t give our consent.”

Those are two of the various comments that Sebastiano Martinoli and Roberto Malacrida, doctors and former university professors in Italian-speaking Switzerland, have heard over the past 30 years when campaigning for more organ donations.

Although both retired from intensive and emergency medicine a few years ago, their influence in Ticino can still be felt. Thanks to their pioneering work, the canton rose from the bottom of the donor list in Switzerland to the top.

The issue of organ donation has been the focus of public debate in Switzerland ever since enough signatures were collected to force a nationwide vote on the initiative: “Promote organ donation – save livesExternal link”.

This calls for the introduction of the principle of presumed consent, whereby it is assumed that everyone agrees that their organs, tissue and cells can be used after their death. Whoever doesn’t want that must ‘opt out’ by officially registering their opposition during their lifetime.

Currently the situation is the other way around, i.e., opt-in: whoever wants to donate their organs can either fill out a donor cardExternal link or tell their family of their wish to donate. Before doctors can extract an organ, they have to consult the dead person’s family to ensure that this corresponds to the wishes of the deceased.

Supporters of the initiative point out that the majority of Switzerland’s neighbours have already introduced presumed consent and donation rates there are around double those in Switzerland.

But is presumed consent really the only practicable way to lift Switzerland out of the group of countries with the lowest donation rates in Europe?

Question of trust

No, say Martinoli and Malacrida without hesitation. They say the proof is Ticino, where the opt-in method yields a similar donation rate to that of Spain, which has the highest donation rate in Europe and which practices presumed consent.

Both doctors emphasise that a decisive factor in determining whether relatives are prepared to donate the organs of their loved one is the level of trust with the medical staff. This relationship needs to be built up, they add.

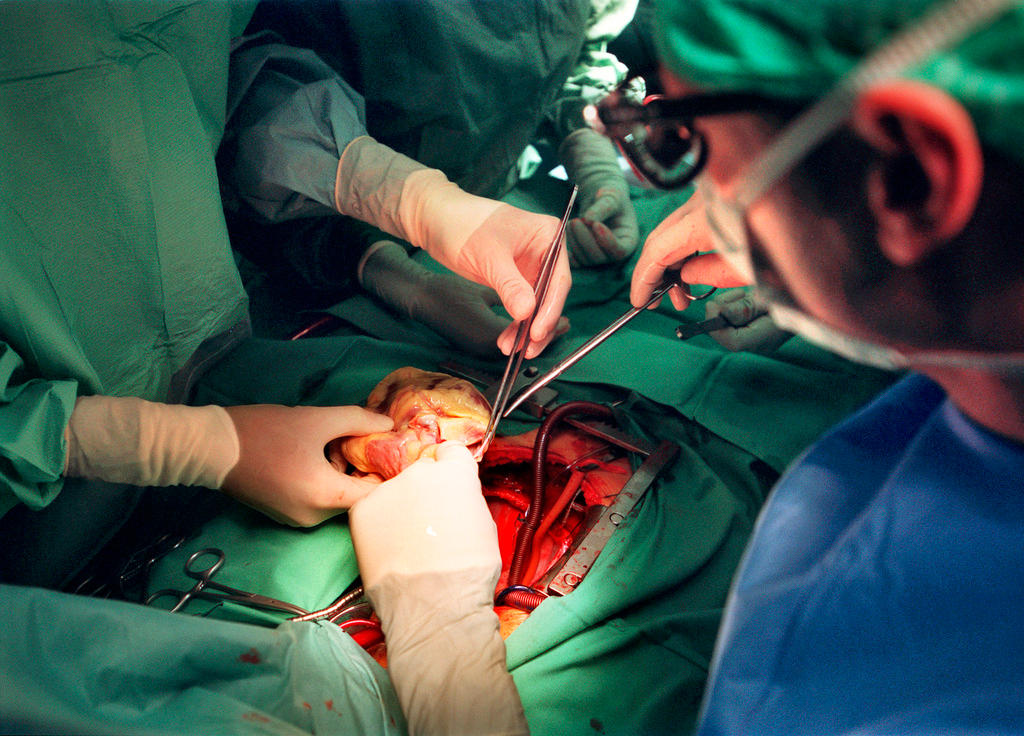

“More than 50% of successful organ donations are down to the work done within the hospital,” Martinoli says. “The crucial thing is that the emergency, intensive and reanimation stations are staffed by well-qualified teams who know all about diagnosing brain death and who accompany the relatives.”

This expertise, he says, requires a good education in psychology and communication.

Good communication requires the right words and enough time, they explain, adding that often, the biggest challenge for doctors is avoiding feeling pressured by the organisational demand for the actual transplant. For the family of the patient to feel safe, time and a calm environment are necessary.

Dealing with silence is particularly demanding, Malacrida says. “Telling people that someone has died is always followed by an initial moment of silence. The family is shocked and the doctor has to keep quiet. He or she must be able to keep quiet – even if it seems to last a really long time,” he says, explaining that he has been through such an experience hundreds of times.

Both doctors categorically reject putting moral pressure on families in order to get their consent. For Malacrida, such a practice would be “ethically unacceptable”.

The people’s initiative means the issue of organ donation will continue to appear in the Swiss media for a while. Will the debate have a positive outcome?

Although Malacrida doesn’t agree with the initiative, he considers the democratic debate triggered by the initiative to be very important – regardless of the result of any vote. In his opinion, the initiative offers the chance to inform the public and address general questions.

Social discrimination

Both doctors warn of the dangers of presumed consent.

“For a start, a large part of the public – especially immigrants – probably isn’t informed. If you don’t know about the official register, you can’t opt out,” says Martinoli, who sees the risk of social discrimination: that organs will be taken above all from marginalised people or people without any family.

They also see the potential danger that presumed consent will be used as a shortcut to save effort when gathering information and talking with people.

“This is the work that’s important for getting consent from relatives who won’t later regret giving it,” Malacrida says.

The initiative’s supporters frequently point to Spain as a model, but Martinoli and Malacrida note that although presumed consent has been written into Spanish law, in practice, family members are still asked whether it is what the dead person wanted.

At the same time, teams of well-qualified doctors, nurses, and psychologists have been created who work together in a coordinated manner, and who look after patients and their families.

That, in their opinion, is the real reason for improved donor figures in both Spain and Ticino.

Translated from Italian by Thomas Stephens

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.