Sanctions: a headache for humanitarian action

As the use of sanctions has exploded over the past few years, concerns are growing about the human suffering they cause. A recent resolution by the UN Security Council that makes it easier for aid organisations to provide help represents a major policy shift, but the issue is highly political and progress is slow. Even so, Switzerland is leading the way on Syria.

Millions of people around the world are innocent casualties of sanctions imposed on their autocratic rulers. So much so that in December, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution to permanently exempt humanitarian activities from such penalties. Aid organisations welcomed the new rules, saying they would help to save livesExternal link.

“We never thought this resolution would be possible just a few years ago,” said Bérénice Van Den Driessche, Senior Policy and Advocacy Advisor at the Norwegian Refugee Council, a humanitarian organisation with worldwide operations. “It was a groundbreaking moment,” she told SWI swissinfo.ch.

However, implementation of Resolution 2664 has had only limited success so far in addressing a problem that usually flies under the radar: funding and distributing aid.

When a country is sanctioned, banks rush for the exits, making it much harderExternal link for humanitarian organisations to get help to the people who need it. The resolution introducesExternal link what’s known as a “carve-out”. It permanently permits the UN and related organisations to send funds and ship goods to countries under sanctions, if they are made in response to an emergency or otherwise support basic human needs.

The text is not a carte blanche. The Security Council requests humanitarian organisations use “reasonable efforts” not to benefit sanctioned individuals or organisations. The carve-out only applies to sanctions imposed by the UN and excludes those initiated by individual states or the European Union.

“Because of these inherent limitations, a breakthrough in humanitarian access in the first year of implementation of the resolution is unlikely,” said Van Den Driessche. “Other sanctions and counter-terrorism measures remain in place which do not necessarily include humanitarian exemptions and continue to impact our operations and hold us liable.”

The United States, which co-sponsored the resolution with Ireland, was the first country to incorporate the new rules into its national legislation. Calling itExternal link a “historic step,” the US Treasury Department issued general licenses in December for aid organisations to work in sanctioned countries.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompted a series of sanctions by the European Union, the United States and wealthy Group of 7 nations on Russian individuals, companies and trade. Switzerland has kept in line with the EU, implementing its tenth package of sanctions last March.

That has not stopped the international community — including NGOs and more recently the G7 — from criticising Switzerland for not doing enough. They particularly point the finger at the limited amount of Russian assets frozen in Switzerland and argue the Alpine nation could do a better job enforcing sanctions.

In this series we look at what steps Switzerland has taken to conform to international standards and where it lags behind. We question the grounds for sanctions and their consequences for commodity traders based in Switzerland. We also analyse Russian assets in the country and understand how some oligarchs are navigating sanctions.

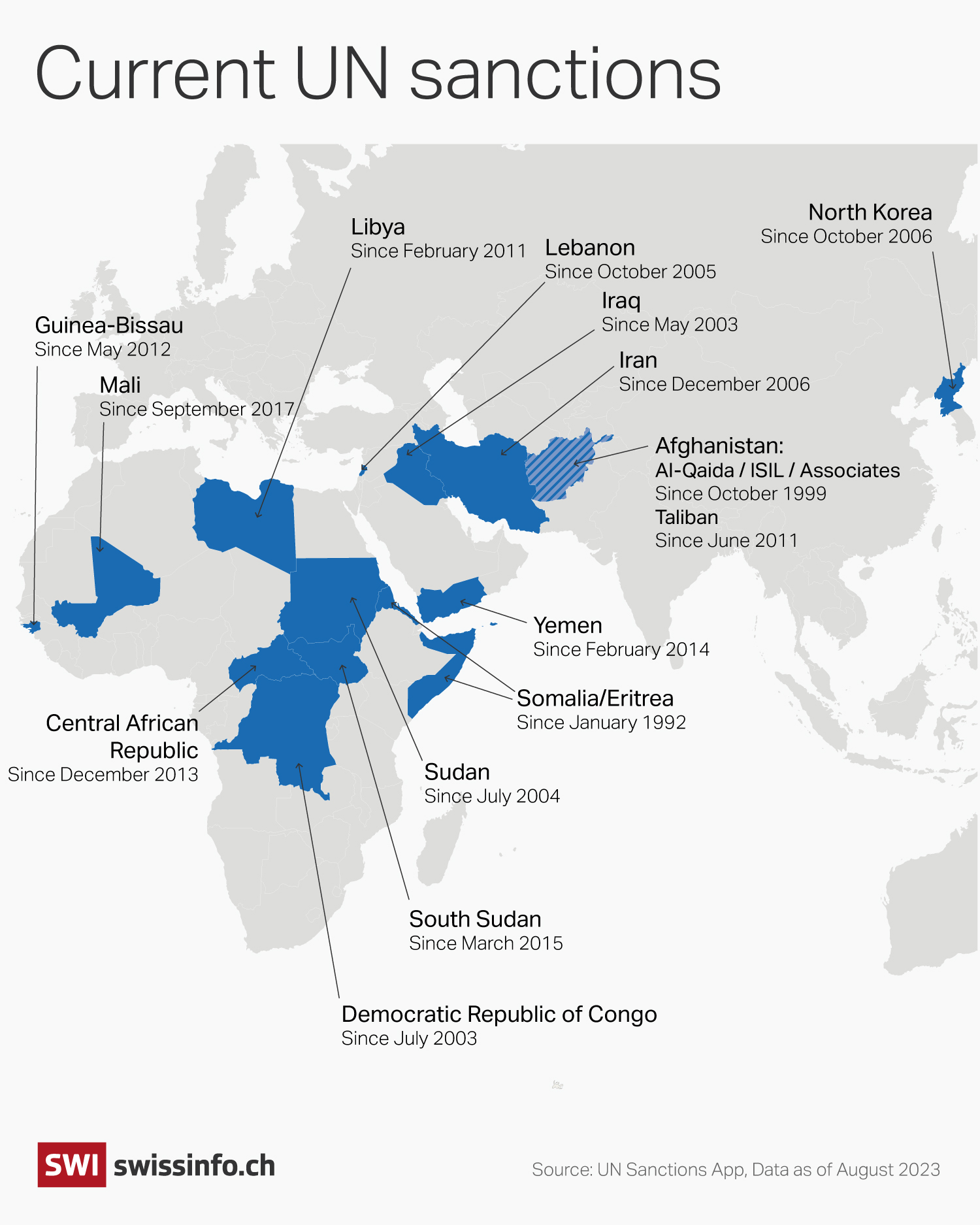

Switzerland implemented the resolution soon after. In April, the government amendedExternal link 13 of its ordinances on UN sanctions regimes, easing the rules for humanitarian transfers to countries like Afghanistan, Iran, Libya, Yemen, Somalia, South Sudan and North Korea. The changes entered into force in June.

“Switzerland stresses the importance of the efforts made by the [Security] Council to ensure that humanitarian aid remains possible and is not adversely affected by the sanctions,” a Swiss delegate to the UN Security Council said in JulyExternal link, citing Resolution 2664. While condemning North Korea’s latest missile test, the Swiss statement added that people’s needs must not be forgotten and their human rights must be respected.

Humanitarian access in Syria still difficult

Yet despite the laudable aims of the resolution, the reality of humanitarian access remains complex and challenging, as shown by the earthquake that struck southern Turkey and neighbouring Syria last February. Tens of thousands of people were killed, buildings collapsed, and schools and hospitals were destroyed.

The disaster hit at a timeExternal link when millions of Syrians were already camped in the northwest of the country near the border with Turkey and relying on humanitarian assistance, having fled the decade-long civil war and persecution by the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. Aid to the area, which is controlled by different Kurdish, Turkish-backed and designated Islamist groups, is delivered either “cross-border” from Turkey or “cross-line” from government-held areas.

After the earthquake, cross-border aid was delayed, with the main crossing point between Turkey and Syria closed for several days. Once it reopened for UN emergency convoys, access remained politically contested. In July, Russia vetoedExternal link an attempt to keep the humanitarian channel open longer-term.

Read more on sanctions and access to aid

Earlier this year, the United Nations was criticized for waiting for Syrian government permission to enter rebel-held territory in northwest Syria and deliver humanitarian aid following a deadly earthquake. This illustrated the kinds of dilemmas faced by aid agencies.

Since 2011, Syria’s civil war has killed over 300,000 civilians and displaced more than 13 million people. It remains one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, but funding is drying up.

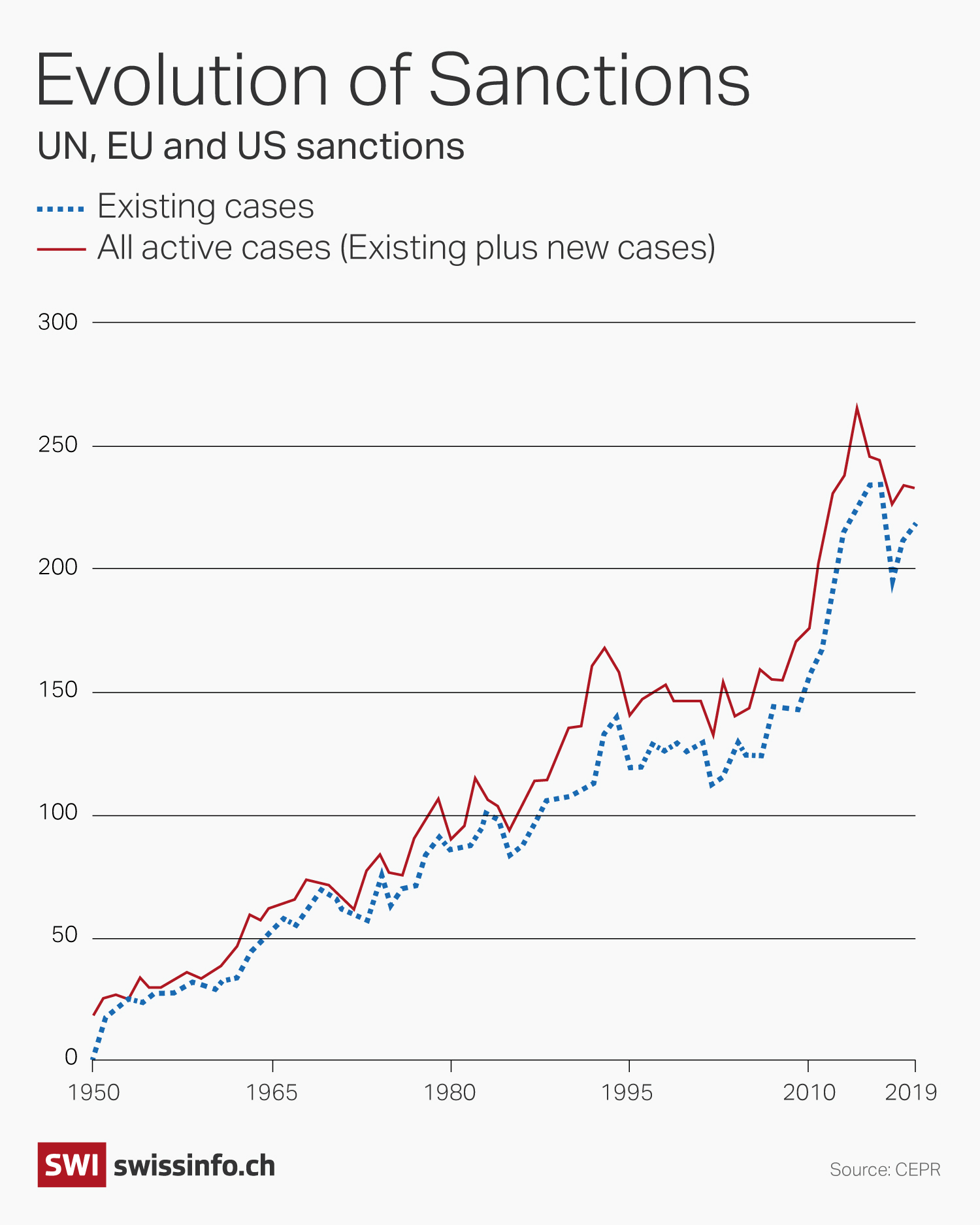

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted unprecedented sanctions. History shows they have been used for centuries, with mixed results.

Meanwhile, cross-line aid has been hampered by sanctions. Resolution 2664 has not eased access in this specific instance, as Assad’s regime is not under UN sanctions but under unilateral sanctions by Western states. This has made it hard for NGOs to import much-needed goods and equipment.

The US and EU were among those that rushedExternal link to issue six-month exemptions to their unilateral sanctions programmes after the earthquake to help aid organisations in Syria get supplies to the quake-hit region. These measures did make a difference, a survey of international NGOs based in Damascus found in May.

With the exemptions in hand, NGOs no longer had to get permits to use necessary services like telephone networks, which previously could take months to obtain. And a few organisations were able to make financial transactions in US dollars and euros, something that had previously been very difficult. Some NGOs started additional projects or engaged with new suppliers.

“We noticed some minor improvements,” a humanitarian aid worker in Damascus who asked not to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue told SWI swissinfo.ch. “But those exemptions could have been more helpful if not time-limited and more harmonised between sanctions regimes.” The six-month limit was a significant drawback, the survey found, concluding that 180 days “is simply not long enough to make a significant impact.”

The EUExternal link extended its humanitarian exemptions in July, but only for a further six months. The US exemption, issued after the earthquake, was not renewed and expired in August.

So far, Switzerland is the only country to adoptExternal link open-ended exemptions. This is widely seen as a positive example and facilitates the work of Swiss-funded humanitarian organisations in Syria, a study published by the Carter Center, a US-based NGO, foundExternal link.

The older, bigger question

Access for aid groups is just one problem thrown up by sanctions. The crisis in Syria raises more fundamental humanitarian questions: how much harm do sanctions imposed on a despotic regime like Assad’s inflict on the civilian population by restricting international commerce? And do sanctions inadvertently increase the need for humanitarian aid? These are issues that Human Rights Watch drew attention toExternal link in a recent analysis of the Syrian crisis.

“The majority of Syrians rely on aid not only because of the earthquake but because of the country’s deepening economic crisis,” the watchdog wrote, pointing out that basic services and the Syrian currency are collapsingExternal link, 90% of the population is living below the poverty line, and the country is ravaged by power outages. Sanctions contribute to the crisis by disrupting supply chains, inducing fiscal crises, and driving up inflationExternal link.

While Human Rights Watch makes it clear that the Assad government and its allies have been the primary cause of the misery in Syria, it findsExternal link that overly broad sanctions compound civilian suffering and deepen the humanitarian crisis. The careful wording of the report underscores just how politicised the topic is.

The original idea of modern-day sanctions was to punish aggressors and help allies. In the interwar period, when world leaders came together in Geneva to craft trade restrictions as a tool of the League of Nations, civilian starvation in enemy territory was accepted as one of the consequences. In his book The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War, Cornell University history professor Nicholas Mulder recountsExternal link how feminist and humanitarian organisations rallied against hunger blockades and how democratic governments struggled with the question.

“The world has made some progress,” said Van Den Driessche from the Norwegian Refugee Council, referring to humanitarian aid to countries under sanctions and the adoption of Resolution 2664. “States certainly want to exert pressure to change the behaviour of a government, but they increasingly recognise the need to spare civilians from their effect.”

Edited by Nerys Avery

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.