Seasonal workers inspired Swiss ‘Together’ movement

In booming post-war Switzerland, foreigners were regarded as mere “labour”. Or even as a problem. The Together movement in the late 1970s tried to counter that with a more welcoming attitude.

Inclusive togetherness instead of exclusion was the motto of this citizen rights movement. Despite failing at the ballot-box, it paved the way for new national policy on immigration.

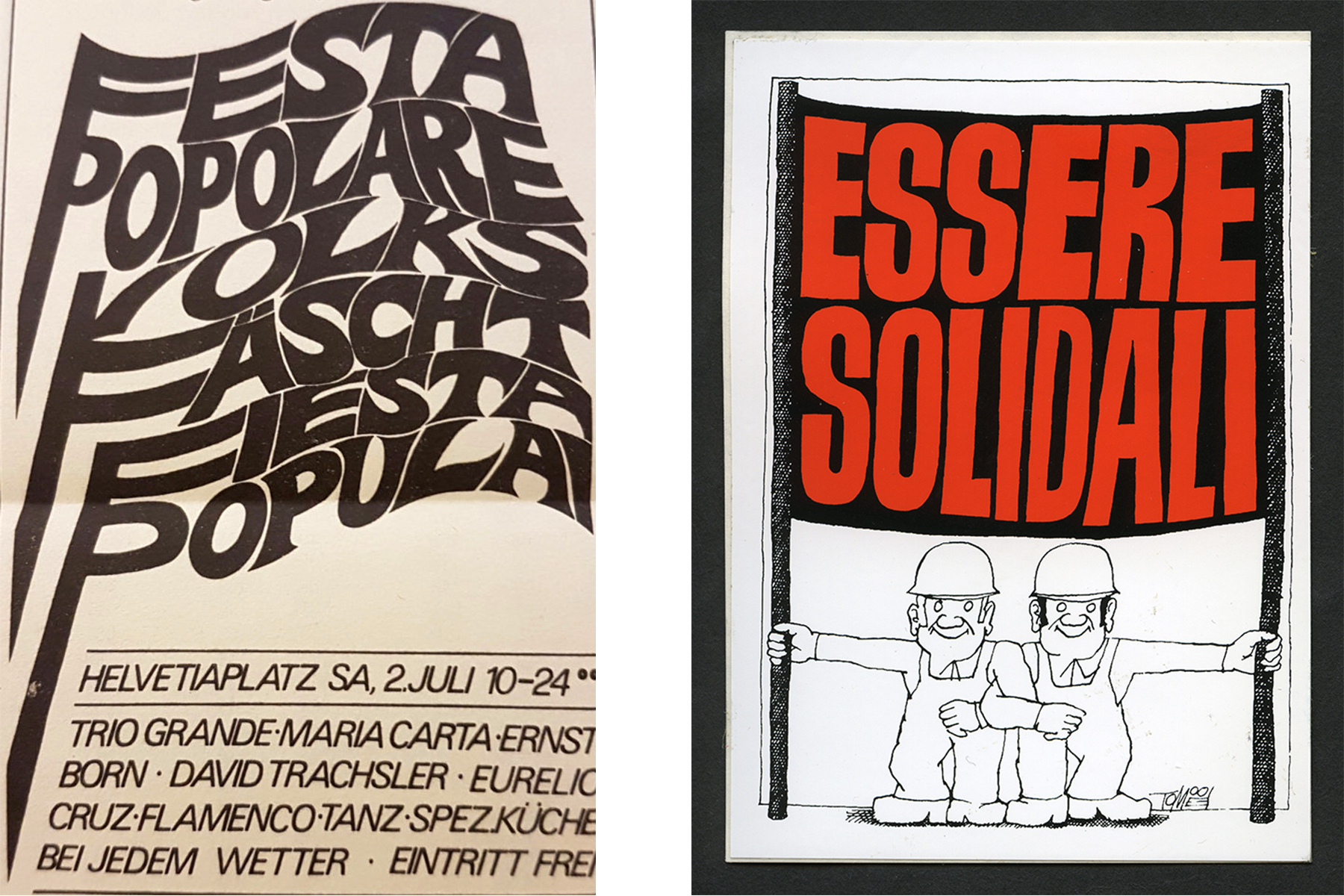

“At the festival there was a colourful mix of booths, music and fine food aromas… Italian and Spanish dishes were well received. You could listen to various folksingers, or dance,” wrote Basel activist Elisabeth Bloesch about a 1978 event organised by the Together movement.

Today that sounds like any multicultural food festival. The June 1978 event marked the fifth edition of the Nostra Festa. The festival was organised by left-wing Italian, Spanish and Swiss organisations which coalesced around the Together initiative. For Bloesch and many others at the time it was a sign of hope for political change. It expressed the dream of a Switzerland where immigration would take place humanely and in solidarity, where the native-born and the immigrant would work together for a common future.

“For us in the Together initiative it was a really enjoyable experience – instead of talking about sections in legislation that needed to be changed, just to see the ‘Together spirit’ shown in a living way,” recalls Bloesch. “Everywhere there were groups of people standing around together, chatting and laughing.”

Bloesch, who wrote about her experience at the festival in the movement’s magazine Bulletin, wondered afterwards: “Was the party just a pleasant dream?”

‘Too many foreigners’

The Together movement emerged in reaction to the hostile view of “too many foreigners” which poisoned the atmosphere in 1970s Switzerland. It started with small-scale street festivals in the German-speaking cities of Basel, Zurich and Bern and came to be known as the Solidarity movement in French and Italian-speaking Switzerland. It put forward an initiative that would have enshrined a humane policy on foreigners in the Swiss constitution.

Democracy is in its greatest crisis since the Second World War and the Cold War.

From a longer-term perspective, this is because of the trend towards authoritarianism and autocracy of roughly the last 15 years.

In the short term, it is because of the coronavirus pandemic and since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Resilience is a key element of the debate about how to handle this multifaceted crisis: democracies should strengthen their resilience and robustness “from within” in order to be better able to fend off threats.

In this SWI swissinfo.ch series, we focus on a principle of democracy that has barely featured in the resilience debate so far: inclusion.

We introduce people who are fighting for “true inclusion” – comprehensive inclusion of all the biggest minorities. We will also hear views from the opposing side, which knows that the political majority in the country is behind it.

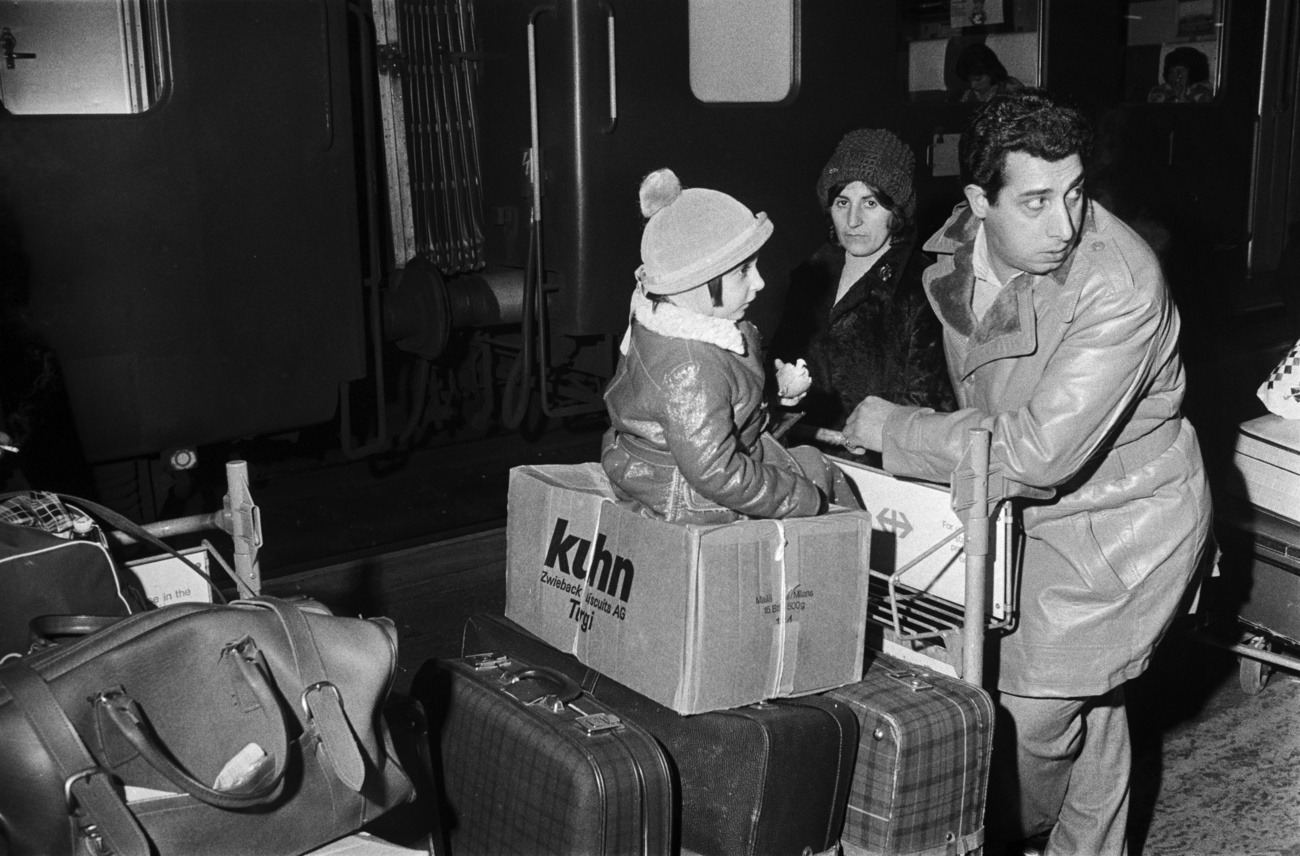

During the economic boom after the Second World War, Switzerland had brought hundreds of thousands of workers into the country, mostly from Italy and other parts of Southern Europe. During this period, 8.5 million first-time residence permits were issued to “foreign workers”. The labour market had dried up in the booming building industry, but also in heavy industry, hospitality and agriculture.

Yet there was a whole range of regulations to ensure that these foreign workers would have to return to their countries of origin as soon as their work was finished. They had seasonal worker status. This meant that they could only be in the country for nine months at a time and their families could not come along.

In the mid-1960s, Swiss working conditions for foreign labour came under international criticism. Increasingly, too, industry lobby groups and politicians here became apprehensive about people going to other countries instead. They came to the conclusion that a part of the foreign workforce should be allowed to settle in this country with their families. So concessions were made, such as allowing family reunification.

More

The Italian seasonal workers in Switzerland

It was clear that the humming Swiss economy was dependent on “foreign labour” for the foreseeable future. The end of the nine-month rotation model in the mid-1960s to a debate over how immigration policy should be shaped to best meet the needs of the country. That debate continues today.

One insistent answer was to turn back the clock. In 1968, a right-wing extremist group that called itself “National action against too many foreigners in our homeland” organised a referendum on what was known as the Schwarzenbach initiative. This initiative proposed that the quota of foreigners in each canton (Geneva excepted) was to be limited to 10%.

The controversies around the “too many foreigners” initiative, as it was also called, were tumultuous. On the day of the vote in 1970, hundreds of thousands of people had their bags packed and were waiting to be told to leave the country. It was a traumatic experience, still burned into the memory of many. Although the initiative was struck down by voters – the 54% “no” vote was still unexpectedly close. That divide is still manifest in current discussions of immigration policy in Switzerland. Back then, some used it as a pretext for violence. In March 1971 extremists supporting the “too many foreigners” initiative in Zurich murdered an Italian, Alfredo Zardini.

Although National Action came from the far right of the political spectrum, this notion of “too many foreigners” was by no means its own invention. It reflected a concern which had been the subject of fierce controversy in Switzerland since the early 20th century: could foreign immigrants adapt to the “Swiss way of doing things”?

Initiative for a new policy

The highly successful film TheSwissmakers (1978) made fun of this restrictive view of assimilation. It captured the petty bourgeois desire for absolute control, and the ongoing suspicion of all foreigners. Meanwhile, in the academic world and in civil society, critical voices began to be raised throughout the 1970s, calling for a rights-based “integration” instead of the condescending “assimilation”. Integration was a new idea at the time that expressed hopes for a different relationship with immigration.

When National Action started campaigning for another “too many foreigners” initiative in 1974, resistance emerged across civil society. The Catholic Workers’ Movement created a working group called Together for a humane policy on immigration.

The Together movement advocated solidarity in immigration policy, and soon enough it became a broad-based coalition. The co-chair of the working group, a clergyman from Valais named Jean-Pierre Thévenaz, recalls that they succeeded in appealing to people and organisations “from the far left to the centre”, from Marxists to church groups and bourgeois liberal groups, in the name of “human rights and justice”. For the first time, too, this was a movement that extended across the different language regions of Switzerland.

The larger organisations of (mostly Italian and Spanish) workers were a part of this alliance. Writing in a Together newsletter at the end of the 1970s, Gianfranco Bresadola, president of the Federation of Free Italian Colonies, an Italian emigrants’ group, emphasised that “only through a lively and effective solidarity can the thousand obstacles before us be overcome.” There should be “unquestioned” support for the Together movement, because it stood for the “best democratic traditions of the country”. In October 1980, a few months shy of the vote, there was a national congress of immigrants’ organisations involved in the Together movement. Their aim, as the announcements of the event stated, was “to get a hearing at last”.

The Together movement was also inspired by political developments on the international stage. There were various human rights and solidarity initiatives at the time. There were attempts to establish rights for migrant workers at the European level. The ecumenical movement was active worldwide. And in the United States the Civil Rights fought for the rights of African Americans.

More

Foreign children forced to grow up ‘in the closet’ call for apology

Like the American Civil Rights Movement, the Together movement in Switzerland worked on the basis that society as a whole had to change, and thus the commitment of civil society was needed. True integration would result from a true democratisation of society.

By 1977, the Together working group had enough signatures collected to call for a nationwide voteExternal link on the “initiative for a more humane policy on foreigners”, as they called it. In 1978, there was a call to a national demonstration in Bern. Booths with political information and ethnic food alternated, and there was a cultural programme consisting of films, music from Chilean refugees, and traditional Portuguese folk-dancing.

That should not obscure the fact that they were demanding political and legislative change, as the chair of the Together working group, Paul O. Pfister, made clear in his speech.

“The women and men assembled here, both foreigners and Swiss, who all live in this country, call on the Swiss people, governments, parliaments and administrations at the federal, cantonal and local level, to extend the principles of humanity and solidarity to the immigration policy of this country,” he said. “We call for a policy based on the idea that the foreigner is a human being with the same rights and social needs as a Swiss.”

The demands of the Together initiative began with the granting of a range of civil rights for foreigners in Switzerland. They wanted family reunification and social security. They wanted a whole new integration policy, involving the participation of both Swiss and foreigners. And they demanded that the controversial, discriminatory seasonal worker status be abolished.

A lasting legacy

Government and parliament recommended that the initiative be turned down. A counter-proposal created divisions in the movement. In particular, the Together demand to abolish seasonal worker status altogether was too much for some to accept. The holding of the referendum was delayed considerably for tactical political reasons, then it was fixed for April 5, 1981. It was roundly defeated by an 84% “no” vote. And this is the main reason why the image of the Together movement has faded in the collective memory of Switzerland.

In spite of disappointment at the high rate of rejection from the people, work for a more humane policy and integration of foreigners went on. Not on the main stage of politics this time, but in solidarity networks and local initiatives. Activists of the Together movement took part in the new debates on integration of the “second generation”. They were also present in the new asylum movement and anti-racist initiatives starting in the mid-1980s.

The Together movement itself came to an end at the start of the 1990s. This was a reflection of changing times. The fall of the Soviet bloc, new globalisation dynamics, and the beginning of the European Union with its proposals for free movement of people, all meant a change of perspective on migration issues. Against the background of these developments, the Together initiative of the 1960s with its advocacy for “foreign workers” had lost much of its relevance. Yet the “Together spirit” mentioned earlier lived on and affected thinking on immigration issues permanently.

Its message was that Switzerland should not see itself – in the words of Swiss literary giant Max Frisch – as something “that had become wonderful” and was now to be defended at all costs, but as something constantly “becoming”, something that keeps having to be reinvented.

Adapted from German by Terence MacNamee/ds

More

How true inclusion can reinforce democracy against crises and conflicts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.