Share your opinions at the workplace – for the sake of democracy

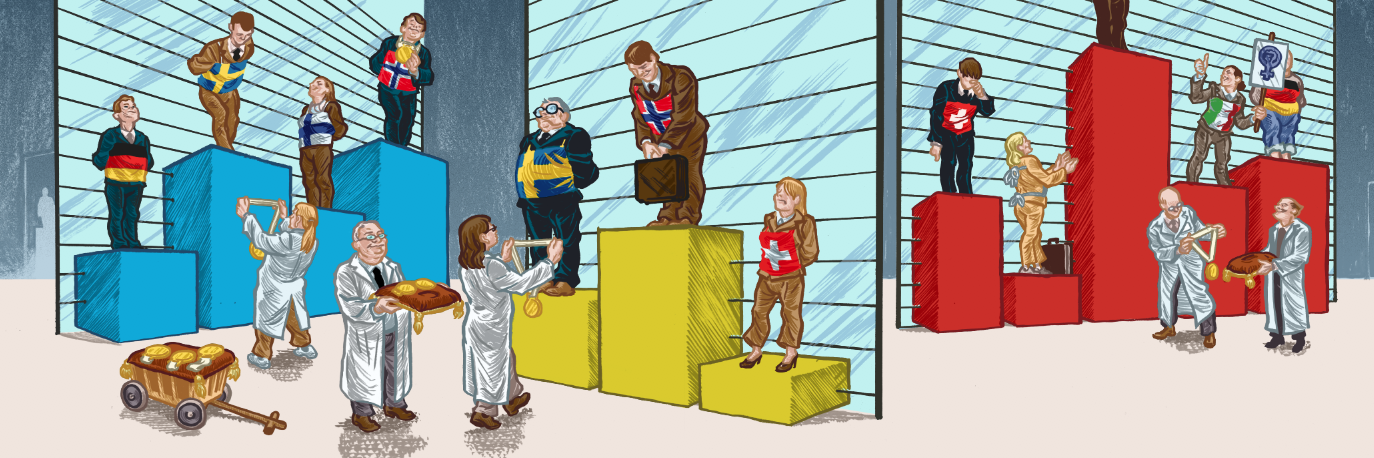

Employees who are allowed to have a say at work are more likely to participate in the democratic process outside the office. But new trends in the labour market are a threat to democracy, warns a Swiss expert.

In 1970, British political scientist Carole Pateman was the first to mention a link between participation at work and democratic participation. She argued that giving employees a say at work can generate positive feelings. These motivates employees to participate more in democratic processes in other ways. Later research found that people who experience democracy at work learn additional skills which can in turn be used outside the office. And these lead to greater participation.

A number of studies, especially in the US, have confirmed the connection between participation in the workplace and democratic participation. For example, research teams have found a positive correlation between union representation and voting participation.

“I think democracy in companies is a prerequisite for democracy to be alive at the state level,” philosophy professor Rahel Jaeggi told SWI swissinfo.ch.

Drivers of discourse

For democracies to thrive they require more than just citizens turning out regularly at the ballot box. They also depend on people participating in public tasks on a voluntary or part-time basis. For example, in Switzerland, democratic participation can take many other forms: from joining demonstrations and collecting signatures to hanging flags and banners outside homes.

But democracy has to be learned, according to Joachim Blatter, professor of political theory at the University of Lucerne.

“You have to learn to be active and to get involved. At the same time, you have to realise that the system requires perseverance and that it’s not enough to just shout out loud,” he said.

But how does this democratic tradition link to the workplace?

Socio-economic issues and interest groups such as trade unions have been central to the formation of political parties – especially centre-left Social Democratic parties – and the associated democratic participation and mobilisation in many countries, says Blatter.

The situation is different in Switzerland where there has never been a particularly strong trade union movement. Can we conclude that the Swiss workplace has been less important as a training ground for democratic processes than in other countries?

“Yes, I would say so,” says Blatter. “But the big differences between countries have blurred over the past 10-15 years.”

In 2017, three economists from the US and Australia published a comprehensive study on having a voice in the workplace and its impact on democratic participation. They analysed data from the 2010/2011 European Social Survey of over 14,000 employees from 27 European countries – including Switzerland. Nine indicators describe the extent of political participation – for example, whether someone voted in the last national election, took part in a demonstration or signed a petition. Four indicators define how much say the respondent has at work – for example, whether they are allowed to determine their own place of work and working hours.

The researchers found that having more say at work increased the likelihood that a person would participate more in democratic processes outside the office. They also found that this relationship was similar across all countries studied.

Where the journey is heading

Despite this connection between work and politics, Blatter says he has observed several worrying changes in the labour market.

In the past, it was possible to have a career and still be active in politics or be a member of an association. Today, international competition is much stiffer, he says.

“If you want to get ahead professionally, you have to put in the hours at work and you hardly have time left for politics,” said Blatter.

As a result, he said, people tend to be more individualistic and focus on themselves and lose sight of common goals – either within a firm or outside the office. His other concern is that people seem to leave jobs if they are unhappy much more readily rather than using their voice to resolve issues.

“Dynamism helps to move people; stability helps to find compromises… and a functioning democracy needs both,” he said.

But Blatter also notes positive developments at work.

Many companies have moved away from paying bonuses based on individual goals, he said. This allows employees to develop a stronger sense of community, something central to democracy.

“Representing your own interests is not enough. You also have to be able to think of others and thus win over majorities,” he said.

The Lucerne professor also believes it is positive that workplaces have become less hierarchical and fewer employees are required to blindly follow orders.

“Today, most people have to decide much more independently how to do their jobs and achieve their goals. In that respect, the working world has become more stimulating for the masses.”

Adapted from German by Simon Bradley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.