Can the Olympic Committee broker Korean peace?

The Swiss-based International Olympic Committee (IOC) says the Korean peninsula has a brighter future due to the North’s participation in the Winter Games. But analysts argue any such rapprochement between the North and South will be short-lived.

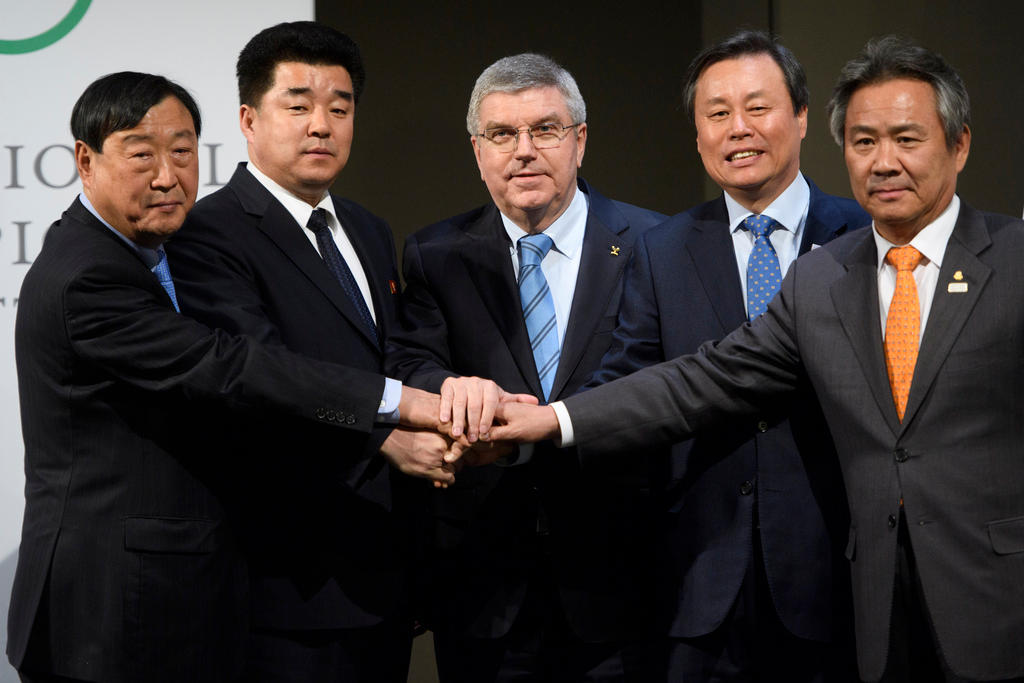

“The Olympic Games show us what the world could look like, if we were all guided by the Olympic spirit of respect and understanding,” said IOC President Thomas Bach after a meeting in JanuaryExternal link with delegates from both Koreas at the IOC headquarters in Lausanne.

At the historic gathering, representatives from the two sides agreed that athletes from the North would not only compete in the Winter Games taking place in PyeongChang in the South, but even march together as one during the opening ceremony and play on the same women’s ice hockey team.

All of that is in line with the Olympic CharterExternal link, which states that the Games should bring athletes together from around the globe to “contribute to building a peaceful and better world”.

But this idea is often far removed from political realities.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in experienced this first hand when his popularity declined following the historic announcement of the joint Korean women’s ice hockey team. Even though Moon was partly elected on his promise to improve relations with the North, the prospect that the integration of players from the North would lower the team’s medal chances was met with little enthusiasm from the South Korean public. (This despite the fact that the 2017 Korean women’s team – with only players from the South – was ranked a lowly 22nd in the world)

“Such a move has its limits,” says Korea expert Samuel Guex from the Department of East Asian Studies at the University of Geneva. “In our opinion, a mixed team is a nice idea but for many South Koreans, this kind of sporting sacrifice is too great.”

The Olympic ideal will also likely be short-lived, argues Guex, forgotten once representatives from the two sides finally sit down to discuss the North’s nuclear programme and the American military presence in the South. Bach’s hopes that the Winter Olympics “are opening the door to a brighter future on the Korean peninsula ” will ring hollow.

“The Olympic Games and the IOC can’t do much about [this reality],”says Guex. In the best-case scenario, he expects economic and cultural cooperation between the North and South to resume in the medium term.

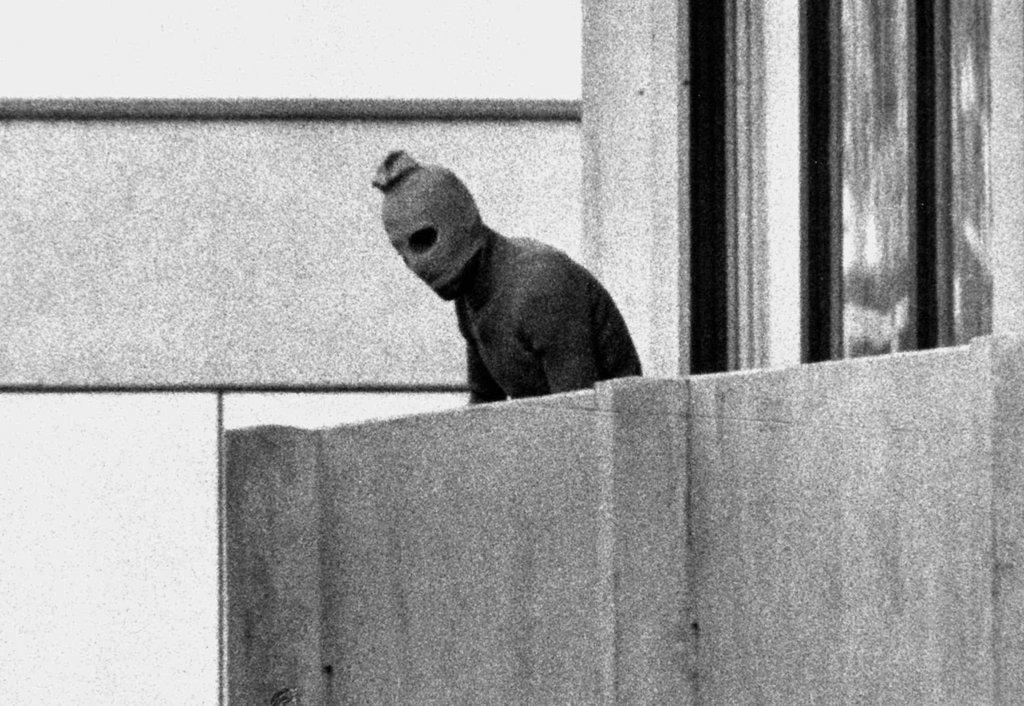

The IOC has often watched its mediation attempts expire once the Olympic torch is extinguished during the Games’ closing ceremony. “Sport has never solved a political conflict,” adds Grégory Quin, a sports historian who teaches and researches at the University of Lausanne. But he thinks the Olympic Games are at least an opportunity for hostile states to meet quietly on the sidelines.

“From a diplomatic point of view, sport is very flexible, and the IOC wants to take advantage of that,” says Quin. Around the beginning of the 21st century, the IOC and the UN began to intensify their relations. On the one hand, the IOC wanted to position itself as a peacemaker through sport. On the other, it intended to play a larger role at the diplomatic level, he explained.

But this was at odds with the body’s stated position that sport has nothing to do with politics.

Quin says the IOC is an opportunist. In the case of North and South Korea, it’s happy to emphasise its role as a mediator. But if the rapprochement between the two sides doesn’t extend beyond the games, the IOC will remind everyone that politics is not its remit.

The IOC did not reply to questions from swissinfo.ch about its role as mediator in political conflicts.

The IOC and the UN – a growing relationship

Relations between the IOC and the UN have been growing since the early years of this century. In 2001, then-UN Secretary General Kofi Annan founded the UN Office on Sport for Development and Peace (UNOSDP) in Geneva. He appointed former Swiss Federal Councillor Adolf Ogi as the first UN Special Envoy for this office.

In 2009, the IOC was granted UN observer status. In the same year, the UN and the IOC jointly organised the first international forum for sport, peace and development in Lausanne.

In 2014, the UN and the IOC reached an agreement on closer cooperation.

In 2017, UN Secretary General António Guterres decided to close the UNOSDP and instead established a “direct partnership” with the IOC.

Sources: UNOSDPExternal link and IOCExternal link

(Translated from German by Dale Bechtel)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.