Swiss citizens with disabilities push for political rights

Swiss activists want people with severe mental or physical disabilities to enjoy full political rights. A Lausanne-based project gives special impetus to this cause. SWI swissinfo.ch paid a visit.

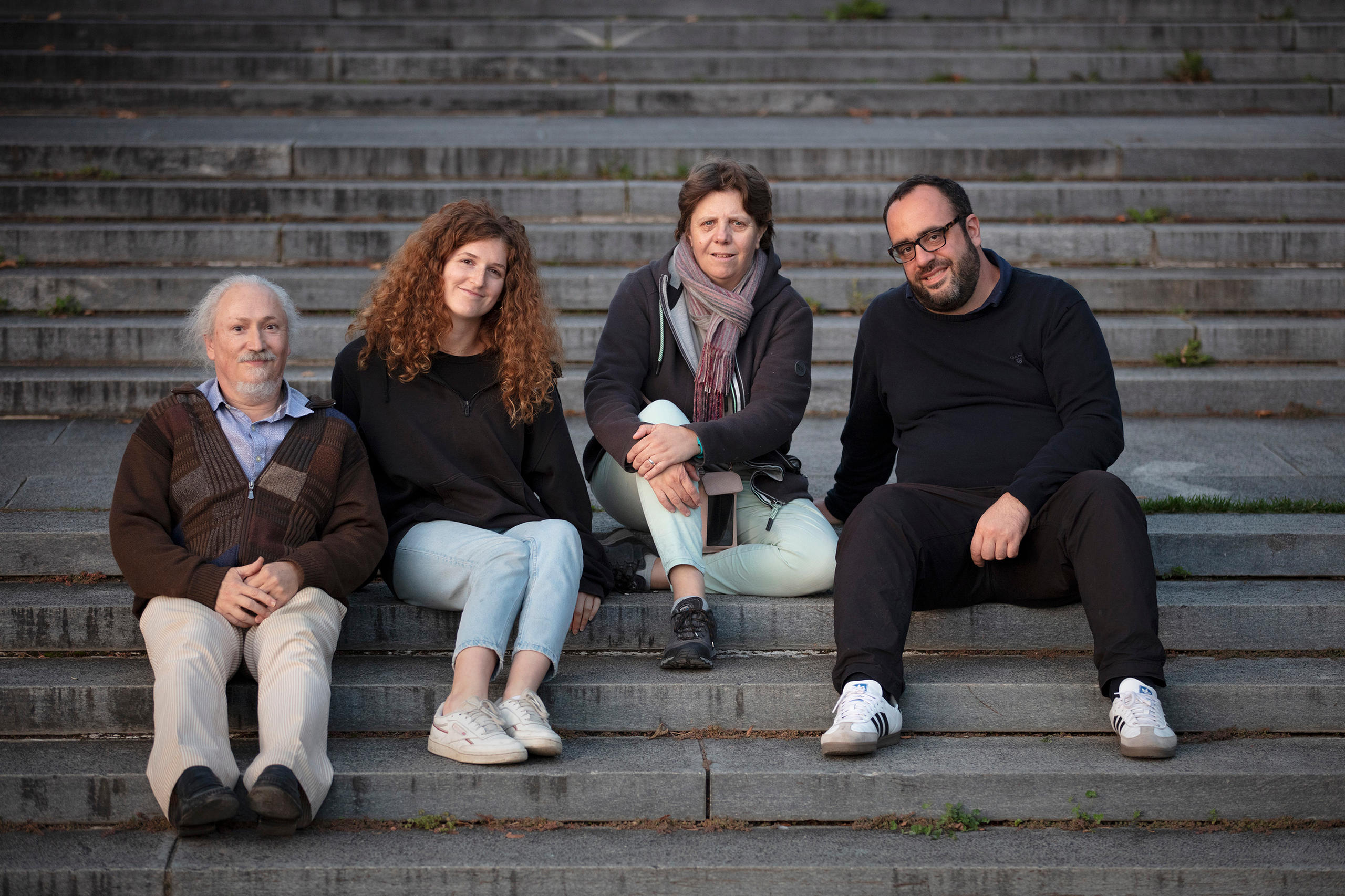

As dusk falls over Lausanne, François Desgalier shares his experiences and aspirations as a person living with a disability in Switzerland. For a long time, he says, he felt like a citizen only on paper. “Now I am simply a citizen,” he tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

That change, he says, came thanks to Switzerland ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2014; and finding opportunities for growth and political expression. One of them is the Bla Bla Vote project, a regular panel discussion and podcast on vote issues.

But to be a citizen, argues Desgalier, you need rights. And Switzerland, despite its strong democratic credentials and ratifying the convention in 2014, hasn’t come far enough in terms of ensuring full political rights for all its citizens living with disabilities. That view is widely shared by advocacy groups and institutions for people with disabilities – as well as by the UN committee responsible for implementing the convention.

15,000 people left out

“About 1.8 million people in Switzerland have a disability, ranging from learning difficulties to serious limitations,” says Desgalier, who has a mental disability. “I’ve always had my political rights, but I know many people for whom that’s not the case.”

In 2020, about 15,000 Swiss citizens were excluded from votes and elections because of disabilities severe enough to require them to have a legal guardian. In addition, Swiss organisations for the disabled documented cases where the voting papers of people with disabilities living in institutional care were destroyed.

The UN charter obliges signatories to ensure persons with disabilities can take part in public and political life on an equal basis with others. That means voting procedures, facilities and materials should be suitable for disabled people. CItizens with disabilities should also have the chance to cast a secret ballot, stand for elections and hold office.

Democracy is in its greatest crisis since the Second World War and the Cold War.

From a longer-term perspective, this is because of the trend towards authoritarianism and autocracy of roughly the last 15 years.

In the short term, it is because of the coronavirus pandemic and since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Resilience is a key element of the debate about how to handle this multifaceted crisis: democracies should strengthen their resilience and robustness “from within” in order to be better able to fend off threats.

In this SWI swissinfo.ch series, we focus on a principle of democracy that has barely featured in the resilience debate so far: inclusion.

We introduce people who are fighting for “true inclusion” – comprehensive inclusion of all the biggest minorities. We will also hear views from the opposing side, which knows that the political majority in the country is behind it.

Those obligations align with Article 136 of the Swiss constitution which states “everyone has the same rights and duties”. But the sentence immediately before restricts who can participate in political life. Swiss citizens who are “incapacitated by reason of mental illness or infirmity” may vote neither in referendums nor elections.

Countries including the Netherlands, the UK, Sweden, France, Italy and Germany have already changed their legal frameworks to allow people with mental disabilities to take part in politics. Switzerland is slowly moving in the same direction.

Winds of change

Canton Geneva in 2020 became the first canton to reform its constitution to allow people with disabilities to partake in political decision-making at the cantonal and local level. Seventy-five percent of Geneva’s population voted in favor. The Swiss government, parliament and some cantons are considering following Geneva’s lead.

Vaud, meanwhile, stands out as a canton where the political rights of people with disabilities are frequently denied or withdrawn. In 2020, 4,000 Vaud residents living with a disability were unable to vote at the cantonal level.

Lausanne-native Anne Tercier, who had gone to every election and referendum since age 18, experienced this firsthand. Tercier’s political rights were revoked in 2018, due to a mental disability, following a change in the cantonal custodianship law.

For Tercier, however, political participation was intrinsic to her self-image: “Voting means being recognised as a full citizen,” she told Swiss public broadcaster RTS. “Because my vote counts, the same as everyone else’s.”

Such media appearances and her dedication to the cause were viewed as game-changers for the Geneva vote. The Lausanne foundation where Tercier lived from 2002 until her death in 2020 celebrates her as “the initiator of the fight for the recognition of political rights for people with disabilities in Geneva and Vaud.”

“Anne Tercier did it: she won her political battle,” says Desgalier, who is an external resident of the same foundation for people with disabilities. “And her case has contributed to a shift in the way politicians view people with disabilities who have been deprived of the right to vote.”

In another win for their community, last autumn, Vaud’s cantonal parliament voted in favour of a proposal to give political rights to everyone with a Swiss passport. Before the vote, the politicians were handed brochures by disability rights activists: “Voting is existing,” the flyers read. As in Geneva, Vaud residents will have the final say in a local vote that has yet to be scheduled.

Participation in action

Desgalier, along with fellow beneficiaries and residents of the Eben-Hézer foundation, is very invested in the outcome. They are in a good position to fight for their cause – running their own newspaper and communications agency, as well as the Bla Bla Vote project’s debates and podcasts.

“The debate is rarely conflictual,” explains Omar Odermatt, a political scientist by training who began at the foundation as a watchman and now co-anchors the discussions. “It’s more a matter of constantly reformulating the arguments of the people who speak, so that all the participants understand what a voting proposal is about.”

Desgalier, who also conducts radio interviews on the history of social insurance in Switzerland, says the Bla-Bla Vote project is all about self-empowerment. He grew up in a home where debating at the dinner table was part of everyday life. His father was a trade unionist. Other participants may be less accustomed to political discussions.

“That’s why it takes time to prepare for Bla-Bla Vote,” he says. The key is to get everyone involved and explain complex topics patiently and in plain language. The Bla-Bla Vote panel discussions are also popular with people without disabilities. No politician has ever turned down an invitation from Bla-Bla Vote.

“These events are really for the local population,” says co-moderator Nadège Marwood from the Chailly neighbourhood centre, which is a partner in the project. “It’s about creating a framework where everyone can express themselves.”

The Eben-Hézer foundation’s commitment dates back to 2014, when Switzerland ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. That was when Véronique Nemeth, an animator at the Centre de Loisirs d’Eben-Hézer, launched “Tous citoyens.” The movement advocates for the implementation of the UN convention and full citizenship rights for people with disabilities.

Bla-Bla Vote was launched in this context offering a forum to discuss issues headed for a vote in simple language. Arguments in favour and arguments against are always presented during the panel discussion, which is also distributed as a podcast.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger

Adapted from German to English by Dominique Soguel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.