Christoph Blocher: ‘The Swiss have to stay out of the EU’

Christoph Blocher’s hilltop home above Lake Zurich is the best known private residence in Switzerland. The modern, cream-coloured mansion, with manicured lawns and a glimmering 21-metre outdoor pool, features in campaign videos for his ultra-conservative Swiss People’s Party (SVP), the most popular political movement in the country.

Blocher is shown cutting the grass with scissors and belly-flopping into the pool. The comic clips, viewed more than 1m times on YouTube, attempt to soften the image of a hardline political party that backs tough restrictions on foreigners living in Switzerland and for Swiss independence from the EU.

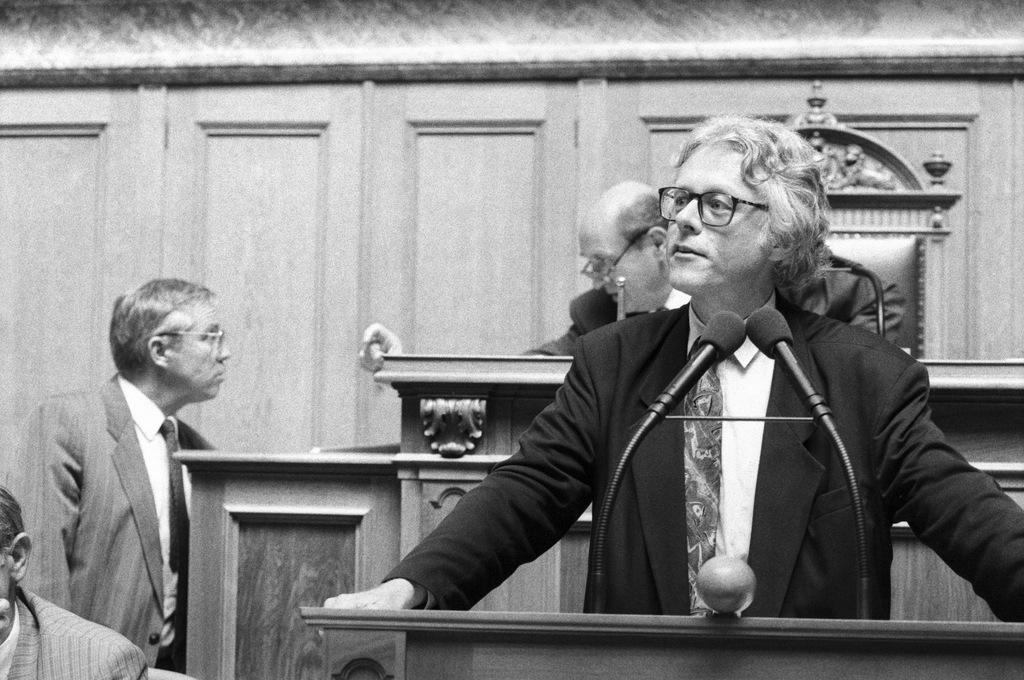

Wearing the same style of straw hat as in the clips, Blocher is in a humorous mood as he greets me on the driveway. A sprightly 77 years old, he apologises for his poor English but proudly notes “an Englishman’s home is his castle” as he surveys his property, built in terraces on the hillside. His cheery politeness and the house’s dreamy setting, with panoramic views of the Alps beyond the lake, belie a bold and arguably highly successful public personality. Not only is Blocher largely responsible for keeping Switzerland out of the EU but, as a businessman, he acquired and expanded Swiss chemicals company EMS-Chemie, bringing riches that allowed a third career as a collector of Swiss art, especially 19th-century paintings. Visiting Zurich earlier this year, Steve Bannon, the former US presidential strategist, extolled Blocher as “Trump before Trump”.

More

Financial Times

External linkEven though Blocher’s brand of politics has become commonplace across Europe, he remains a controversial figure. Campaign posters for the SVP have portrayed foreign offenders as “black sheep”; the party is seen by many as tarnishing Switzerland’s international image and disrupting its tradition of government by consensus.

Blocher leads the way down a winding red-brick path to the pool, past patios and rosebeds. Each day in summer he swims 500 metres breaststroke — two widths and the diagonals repeated 10 times — and drinks his morning coffee. The SVP videos were meant as a joke at his expense. Self-deprecation is not a national trait, he says. “That is not Swiss . . . that is why it was so special.”

Up some steps to one side, a flagpole flies the Swiss flag. It is a reminder that Blocher’s career has been spent defending decentralised Switzerland against mass incursions by foreigners — whether EU directives or migrants attracted by its affluence. “We don’t have very much land in Switzerland — we’re a small country,” he says.

The canton of Zurich was his original power base in the 1970s. “If the canton of Zurich was endangered, I would run up the Zurich flag,” he says.

Churchill never thought of an EU such as we have and, above all, he never thought the British would join

Blocher bought the site in 1998 after his four children had grown up (he also has 12 grandchildren) and rebuilt the original house for himself, his wife Sylvia and his art collection. The exterior is surprisingly neutral — neither traditional Swiss nor an example of the country’s architectural avant-garde. The only embellishment is a tower with a wind vane. How would he describe the style? “Style-less,” he laughs.

Beneath us, built on an old meadow, are the offices of EMS. “I could walk to work,” he says. He started working at EMS as a lawyer in 1969 and bought a majority stake in 1983.

Since 2004, when Blocher became a government minister in Bern, his daughter Magdalena Martullo-BlocherExternal link has headed the group, continuing its expansion to achieve a market value today of SFr15bn ($15.05bn) and sales last year of SFr2bn; just 3 per cent of those are to Switzerland, which Blocher says means he is no Swiss “nationalist”.

He has also wound down his political career. His chief remaining responsibility is heading a Swiss committee whose title translates as “No to creeping EU membership”, and which campaigns against steps it believes drag the Alpine country closer to formal membership.

The high point of his career, he says, was leading the successful 1992 campaign against Swiss membership of the European Economic Area, which would have been a stepping stone to joining the EU. Submission to EU law would conflict with a Swiss constitution based on power lying ultimately with the people via frequent referendums, Blocher says. Though surrounded by EU members and dependent on the bloc for trade, avoiding formal membership was “the most important thing I have achieved”.

Blocher’s house has no television but he says he has seen Darkest Hour, the 2017 film about Winston Churchill, three times. The story of the UK prime minister’s wartime leadership — though not historically accurate — was a reminder of the loneliness of political decision-making. Churchill supported European unity, I point out. “But he never thought of an EU such as we have and, above all, he never thought the British would join,” Blocher replies. He reserves judgment on much of Donald Trump’s policymaking but notes that the US president at least “tries to do what he promised”.

The low point of Blocher’s career was in Bern. The Swiss federal government is run by a seven-strong council of representatives of the biggest parties. Blocher lasted from 2004 until December 2007, when he was ejected by parliamentarians. By then, however, he had overseen Switzerland’s preparations to join Europe’s passport-free Schengen zone — despite his fierce opposition. “That went badly with the people,” he says. “We don’t have it under control any more.”

Entering the house, Blocher flicks a switch to open the blinds, revealing a large white-walled living space that serves as gallery for paintings by Albert Anker and Ferdinand Hodler— two of Switzerland’s best-known artists. In total, he has about 200 by each. Blocher started his collection in the 1970s, “when I had a bit of money, but not yet a lot”. It was sold to help fund his purchase of EMS. “Then, when I had money again, I started again. In some cases, I bought back the same pictures — but at a higher price.”

On the wall behind a table is his favourite Anker painting — his 1886 “Portrait of a Girl” — of an unnamed child wearing a neckerchief and pensive expression. She represents all childhood and shows “the world is not damned”, says Blocher. The painting is “better than the ‘Mona Lisa’ ”, he says. The colours are more vibrant and “Mona Lisa is a boring woman.”

Blocher was the seventh of 11 children. His father was a church minister. Across the living room is a tiled stove, built in Steckborn on Lake Constance in 1729 and used for heating. It has biblical inscriptions around its base. “On Sundays I don’t have to go to church. I can just stand by the oven,” says Blocher.

High security

We descend a wide staircase to a labyrinth of high-security underground corridors and rooms housing much of his collection. Other works are in his castle, Schloss Rhäzüns in Graubünden, which borders Austria and Italy. It seems a shame the works are not in public museums. Blocher says he lends them out “generously” for exhibitions, which he argues are better at generating audience excitement. “We have too many museums and they are poorly attended.”

Finally, we emerge from a downstairs door on to an outside terrace. Storm clouds have gathered over the mountains and are moving up the lake.

Blocher says the rise in neighbouring Italy of Eurosceptic populist politicians proves his argument that the EU was a “misconstruction”, especially the eurozone. “A euro is the same in every country — but all countries are different.”

He thinks the UK took the right decision in voting to leave the EU. “That can bring freedom to the British and give them an economic lead as well. But at the beginning it is difficult . . . Leaving is more difficult than never joining.”

Brexit storm clouds are reaching Switzerland, however. Since the early 1990s, the country has negotiated a web of bilateral deals with Brussels. Now the EU is rethinking the way it treats “third countries” and wants a new deal with Bern — one that would bring the country closer into line with its rules and under the jurisdiction of its judges. Blocher shows his belligerence. “They [the EU] don’t like citizens always having [a] say,” he says. He set Switzerland’s strategy 30 years ago. “I am proud that I did that because we are still a free country.”

Favourite thing

The house has been rebuilt to accommodate his collection of paintings. But one picture dominates — the view from the windows and garden terraces.

On a clear day, Blocher says, it extends across 19 of Switzerland’s 26 cantons, and as far as the Eiger and Jungfrau mountains, each around 4,000 metres high. Below, the lake stretches towards the city of Zurich, its blue waters dappled with sailing boats and ferries.

“I’m surrounded by paintings. This is another one — and it changes every day,” says Blocher.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.