The (long) wait continues for the UN’s human rights report on Xinjiang

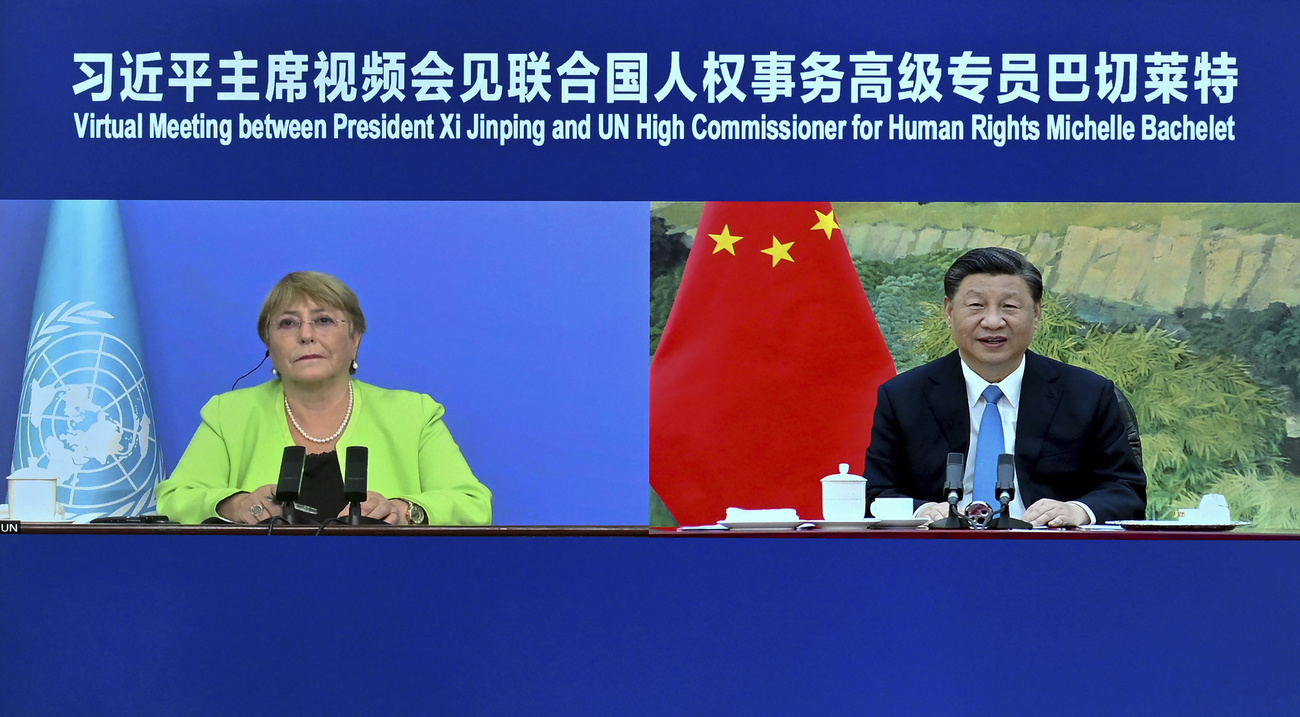

Over a year ago the United Nations Human Rights chief Michelle Bachelet promised a report on the treatment of China’s Uyghur minority. As she is about to leave office, human rights groups are still waiting.

Rights groups and journalists had hoped Bachelet’s final press conference would offer a clear answer as to when her report on China’s treatment of its Uyghur minority in Xinjiang province would be published. As head of human rights for the United Nations, she had committed to publishing it before the end of her four-year term on August 31. Her response that she would “try” to publish it “on time” came as a frustration to rights groups which have been waiting over a year for her assessment.

“It would be shameful for Michelle Bachelet to abandon Uyghur victims of crimes against humanity by Chinese authorities, and leave office without publishing her Xinjiang report. She needs to keep her promise, uphold the integrity of her office, and demonstrate that she stands with victims, not violators,” John Fisher, deputy director of Human Rights Watch said after the press conference, held in Geneva on Thursday.

The report has been a source of tension between human rights groups and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for years. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), UN special rapporteurs and other independent expert groups have raised the alarm and produced credible reports accusing Beijing of widespread and systematic abuses against the Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang, including forced labour in detention camps. However, Bachelet’s office has bounced the ball back and forth, promising but then never publishing a report on the situation there.

For rights groups, publication is important. It would be a first step towards holding China to account for what many have called cultural genocide. Though the report cannot impose binding measures, it will have a moral impact and can lead the way to further investigations. It could also potentially lead to a resolution at the next session of the Human Rights Council.

“The challenge is that, as much important work as the rapporteurs have done, it doesn’t have the imprimatur of the UN secretariat, the UN as an institution. There’s a difference, and I think a very important difference,” said Sarah Brooks, a programme director at the NGO International Service for Human Rights (ISHR).

Several special rapporteurs have published independent reports on Xinjiang and forced labour since 2018. In 2020 for instance some 50 special rapporteurs and independent experts released a statement asking China to protect fundamental rights. The call was repeated in 2022. Special rapporteurs are mandated by the Human Rights Council but their reports don’t carry the weight of a formal UN report. China to date does not have a dedicated China special rapporteur.

Long in the making

First mention of an official report by the Human Rights Council dates back three years. At the time NGOs and international media had already documented evidence that China’s Uyghur minority was being sent to detention camps from as early as 2017.

For years, Bachelet tried gaining access to China to supplement the report, but Beijing never accepted the conditions required for an independent fact-finding mission, which would include meaningful, unfettered and independent access. In September 2021 Bachelet announced that her office was finalising its assessment of the rights situation in Xinjiang ahead of publication.

More

What it takes to be a UN human rights chief

In December 2021, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) once more announced that the report was reaching its final stage and that it would be released in a matter of weeks. But again, the report was kept in a drawer. The OHCHR never provided a reason for not publishing. A few weeks later, reports emerged that Bachelet would be allowed a visit to Xinjiang after the February 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

The reason for the persistent delay of publication can only be speculative. Some rights groups say Bachelet was bowing to pressure from China; others say she was negotiating behind closed doors to gain access to the region. All agree the confusion and lack of communication has tarnished her legacy.

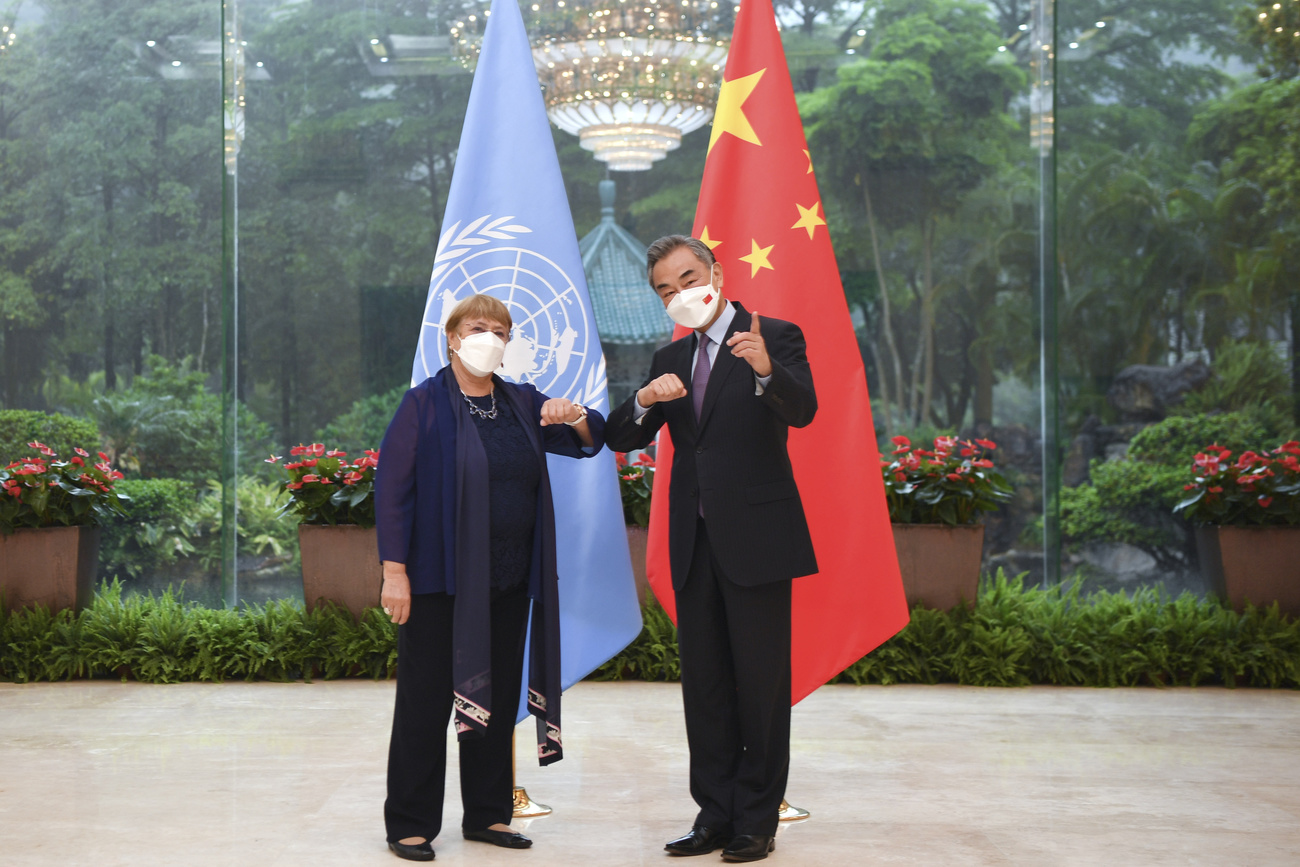

A visit to Xinjiang finally took place over six days in May. Chinese officials insisted it was “friendly”, and the High Commissioner said it was not an investigation. Journalists were not allowed to join the mission and the terms agreed to allow it to go ahead were never made public. Bachelet confirmed she “was not able to speak to any Uyghurs currently detained or their families during the visit”. She also said she was accompanied by government officials throughout.

More

UN rights chief in China: walking a tightrope between engagement and risk

On Thursday, when asked to elaborate on why the report still had not been released, Bachelet said she needed time to integrate new information from her visit and to review input on the report’s contents from China.

“My interpretation of the length of preparation of the report is that it was about making sure that every ‘t’ was crossed and every ‘i’ was dotted. And that takes time when you’re working in an organisation like the OHCHR,” said Brooks, who stresses the importance of producing a credible report. “If it’s done well – with integrity and with a strong methodology – it becomes very hard for there to be anything other than politically motivated complaints about it.”

War of words

For China there is much at stake. The report has become an argument for the world’s second-largest economy to accuse the West of smearing its efforts to promote peace and fight terrorism. It has carefully crafted a narrative saying its repressive measures in Xinjiang province have enabled peace, stability and economic growth in the region, providing jobs and training. It argues the Uyghurs are in vocational training camps learning skills and not – as rights groups claim – in detention camps.

NGOs have estimated that at one point at least one million people were incarcerated, with victims reporting use of systematic torture, forced sterilisation, and rape. The latest research suggests a total of eight million Uyghurs may have been incarcerated since 2017.

China has put all its diplomatic weight into getting the OHCHR to bury the report. In July, Reuters news agency reportedExternal link that Beijing had circulated a letter among diplomatic missions in Geneva urging Bachelet not to release the report. On Thursday Bachelet confirmed she had received the letter which she said was signed by about 40 other states, adding that her office would not respond to such pressure.

With the deadline for publication looming, Beijing has flooded social media with official and unofficial accounts portraying positive assessments of its policies and whitewashing all evidence of human rights abuse.

Many questions remain regarding the content of the report. Rights group worry that when the report eventually comes out, it could be a watered-down version that plays into Beijing’s narrative.

“It is also critical that the report accurately reflect the scale and gravity of the violations, which Human Rights Watch and many others have concluded rise to the level of crimes against humanity. We would expect no less of any credible independent assessment by the High Commissioner,” Fischer says.

During Thursday’s press conference Bachelet reiterated that she would not “withhold publication” despite the “pressure” she was under. In mid-August, an independent expert appointed by the UN Human Rights Council released a reportExternal link saying it was “reasonable to conclude” that Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region were being subjected to forced labour.

China’s foreign ministry was quick to lash out and slammed the report calling it lies and disinformation “spread by the United States”.

More to come?

Rights groups argue that a report by the OHCHR could allow for more voices to express concern about China’s alleged rights abuses. Many countries, including in the Middle East, have been unwilling to criticise publicly China’s Xinjiang policies.

“[Chinese President] Xi Jinping has repeatedly said that he wants an international system with the United Nations at its core. China’s emphasis on the UN makes it nearly impossible for the Chinese government to ignore credible criticism coming from the UN. Politically, also, an authoritative report by the UN could give the political space for many Global South countries to voice concerns,” said William Nee, research and advocacy coordinator at Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD).

“What the UN says will have immense value in impacting people’s lives in Xinjiang.”

Additional reporting by Akiko Uehara, Virginie Mangin

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.