The ‘Swiss Schindler’ who saved the Greeks of Smyrna

The fire of Smyrna in 1922 was one of the greatest tragedies of the declining Ottoman Empire. The Swiss industrialist Herman Spierer unexpectedly became the saviour of the fleeing Greek population.

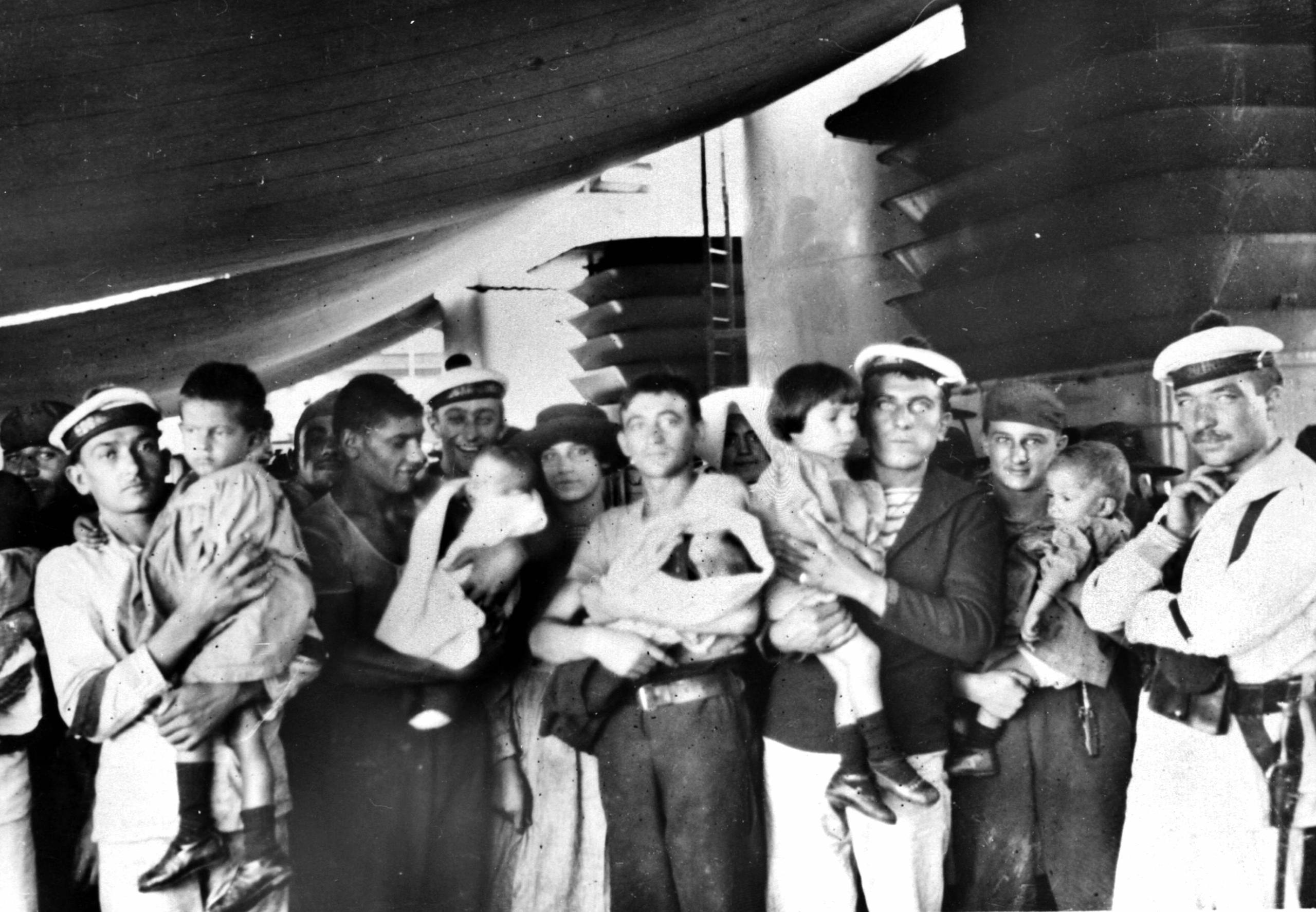

Apocalyptic scenes confronted the survivors fleeing on ships in September 1922 off the harbour of Smyrna, today’s Izmir, on the Turkish Aegean coast. Against the backdrop of the burning city, more and more people gathered on the long quay.

Hundreds of thousands were trapped between the flames and the sea during the nine-day catastrophe. They could not escape along the coast, because the Turkish troops who had marched into the city shortly before the fire were blocking their way.

While American, English, French and Italian troops watched the bloody spectacle passively from warships not far away, people died like flies. It took three days before these nations ordered their ships to begin a rescue operation and help refugees to escape to Greece. It is largely thanks to the stubborn persistence of the YMCA youth organisation that they got involved at all.

Private engagement

Some private individuals, who organised the evacuation of civilians on their own initiative and at their own expense, demonstrated more willingness to help. Among them was Herman Spierer, a Jewish-Swiss merchant who was born in Smyrna and was one of the city’s most important tobacco industrialists.

While Spierer remained largely unknown in Switzerland, he was celebrated in Greece for decades to come as a saviour of countless Greeks as well as a philanthropic entrepreneur. In Greece, he was also compared to Oskar Schindler, who rescued Jews in the Holocaust, because he took individual action and put himself at risk to save lives.

Multicultural city

Herman Spierer was a typical example of the so-called Levantines: European families who lived mainly as merchants and industrialists in the Ottoman Empire and were under the protective rule of their home countries. They were another stone in the ethnic mosaic of cosmopolitan Smyrna, where Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Turks lived at that time.

Spierer, whose family came from Geneva, maintained production facilities and warehouses in the city and employed mainly Greek workers. The majority of the approximately 700,000 inhabitants of the region were Greek. At that time, more Greeks lived in Izmir, which is now part of Turkey, than in Athens.

However, multicultural life in the city, which the Turks called “infidel Smyrna”, came to an abrupt end in 1922. Kemal Atatürk’s troops took the city. It was the last conflict in the Turkish War of Liberation. Three years earlier, Greek troops had occupied Smyrna in accordance with the Treaty of Sèvres, which provided for the dismemberment of the collapsed Ottoman Empire.

Enormous death toll

In an ultra-nationalist frenzy, the Greeks set out to attack Ankara, over 500 kilometres away. They were defeated by Atatürk’s troops and had to retreat to Smyrna, followed by 150,000 Greek civilians who had fled to the coast from inland.

While most of the soldiers were shipped home, the civilians were left defenceless in the city. What followed went down in history as the Asia Minor Catastrophe and ended a Greek presence in Asia Minor that had existed since antiquity.

The death toll was enormous: an estimated 100,000 people died in fighting and massacres in and around Smyrna, and 100,000 more were deported inland, where most of them perished.

What began on a military level was later completed on a diplomatic level. The separation of Greeks and Turks, who had lived side by side for centuries, was sealed with a contractually agreed, compulsory population exchange. Up to 1.5 million Christians had to leave the new Turkey for Greece, while half a million Muslims took the opposite route. Many of them were settled in the depopulated port city.

Funding the evacuations

Spierer was on a business trip in Europe when the news from his hometown reached him. He returned to Smyrna immediately. Confronted with the murderous chaos in the city, he opened his warehouses so those fleeing could hide in them.

The buildings were under the protection of the Swiss flag. The Turkish soldiers had orders to leave the lives and property of the “Europeans” untouched. Nevertheless, a large number of them later fell victim to plunder and fire.

Spierer managed to save hundreds or thousands – sources vary on the numbers. Together with his brother Charles, he organised ships to transport the refugees to Greece at his own expense.

When the fire on the other side of the Aegean died down, much of the city lay in ruins. Greek Smyrna ceased to exist and Turkish Izmir took its place. Most of the Levantines, some of whom had lived in the Ottoman Empire for generations, also migrated back to their countries of origin, among them the Spierer family.

National benefactor

Many of the Greeks rescued by Spierer were later settled in northern Greece, where “Herman Spierer and Co.” operated numerous factories. Spierer ensured that they found employment with him. He continued to support widows and orphans financially for a long time.

The Greeks did not forget his help. The Greek bishop of Smyrna called him a “great national benefactor”. Rescued refugees are said to have carried his picture next to images of saints. Spierer died in 1927 in Trieste, where the family business had moved in the meantime. He was only 40 years old. His death was extensively reported in the Greek press at the time.

In addition to his philanthropic work, his economic activities were also praised. He had created urgently needed jobs in the economically battered north of Greece and ensured that Greek tobacco was exported to numerous countries.

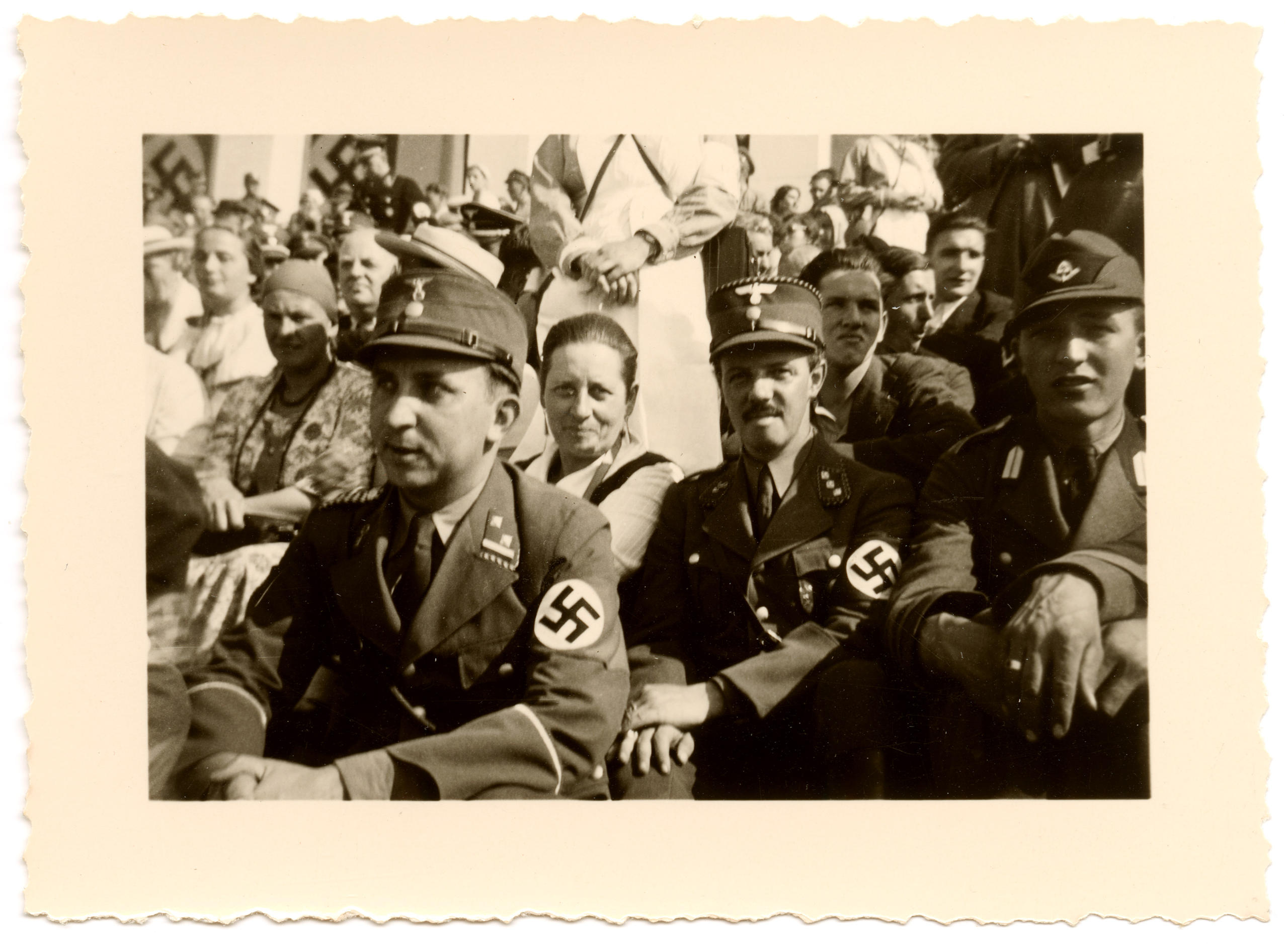

Incidentally, Herman Spierer’s son Simon – born only one year before his father’s death – kept up the family’s philanthropic tradition. In 1943, he fled from the Nazis to Geneva. His mother and sister perished in concentration camps.

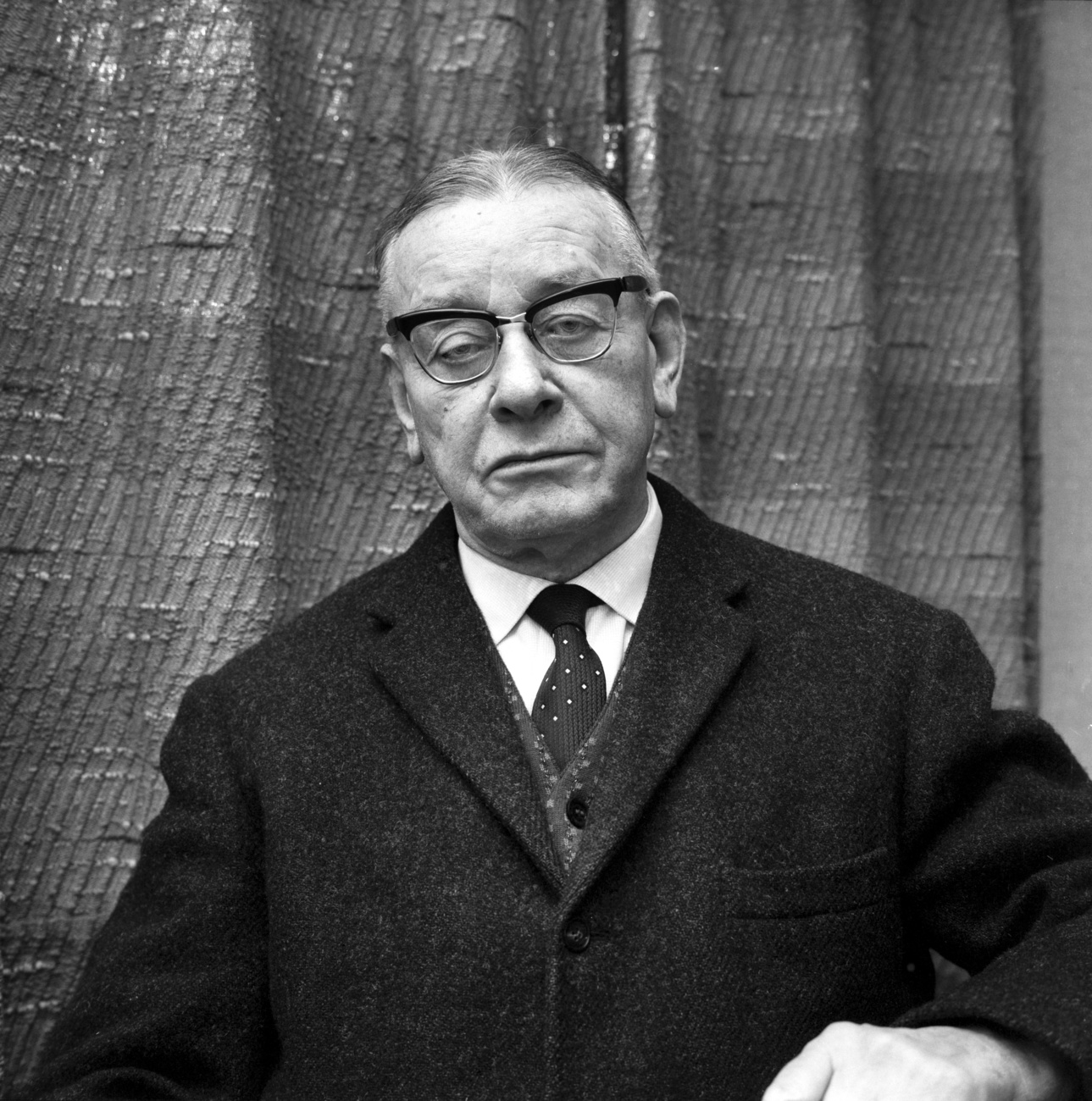

Simon Spierer also made a fortune in tobacco. He began collecting fine art in the 1980s and became a friend of Andy Warhol. A year before his death in Geneva in 2005, he donated his “Forest of Sculptures” to a German museum. The collection consisted of works by Alberto Giacometti, Max Ernst, Max Bill and Hans Arp, among others.

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley/ds

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.