‘Putin has forced this crisis diplomacy upon the West’

The US-Russia talks in Geneva are a victory for Vladimir Putin, who has imposed his agenda on the West while the European Union is marginalised, analyses Gwendolyn Sasse from the Centre for East European and International Studies at Humboldt University.

A flurry of diplomatic activity is the Western response to the new Russian military build-up close to the Ukrainian border and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s demand for a formal agreement to stop NATO’s eastern enlargement. Phone calls between US President Joe Biden and Putin have prepared the ground for negotiations between representatives of the US and Russia in Geneva on January 9-10, as well as the NATO-Russia talks on January 12 and a meeting of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) on January 13.

The talks in Geneva will set the tone for the rest of the week. Switzerland will feature in its role as a neutral country hosting protracted international negotiations. At the same time, Switzerland will be more than a neutral observer if potentially far-reaching financial sanctions are tabled vis-à-vis a US-Russia diplomacy reset.

More

US-Russia talks held in Geneva amid tension over Ukraine

New approach

This quick succession of high-level diplomatic meetings involving the US and NATO marks a departure from recent years of minimal contact. It is borne out of the urgent need for de-escalation in a situation that could easily spiral out of control – either by choice or as the result of a loss of central control over developments on the ground.

Putin has forced this crisis diplomacy upon the West, and from his perspective this already counts as a success: it visibly demonstrates to the world, and to Russian citizens and elites, that Russia is a globally significant power to be reckoned with. US President Biden has chosen to treat Putin as an equal on the international stage, thereby widening his focus beyond China as the main US adversary. It is this belated recognition of the global standing of post-Soviet Russia that is one of two main Russian foreign policy goals. The second objective is maintaining or re-establishing Russia’s influence in selected neighbouring countries, above all in Ukraine, but also in Georgia, Belarus and – as current events demonstrate – in Kazakhstan.

The series of diplomatic exchanges this week will test the scope for a new kind of Russia-US diplomacy based on clearly-stated diverging interests. Putin has already effectively limited this scope by publicising the key documents he wants to discuss. The Russian position is phrased as a list of demands that cannot be fulfilled and leave little room for actual negotiations. It is therefore entirely possible that Putin simply aims to instrumentalise this round of talks as a Western failure to respond to his willingness to negotiate, providing him with the domestic legitimacy to increase the military pressure on Ukraine.

More

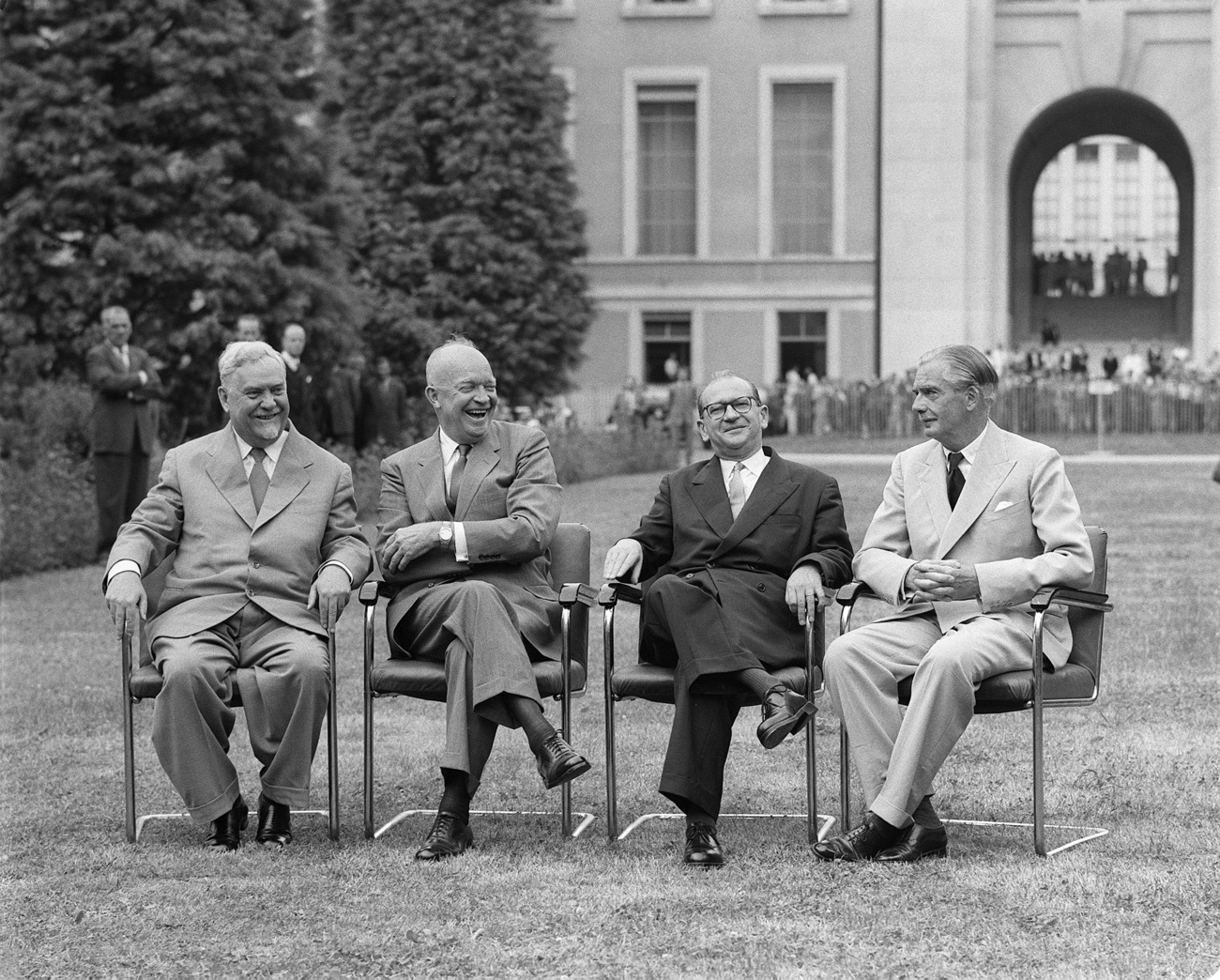

US-Russia summits then and now: High tensions, mixed results

Most importantly, Putin is insisting on a formal agreement that rules out NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia and limits NATO military deployment along its eastern flank as well as US military support for Ukraine. Behind these concrete demands lurks the call for a new security architecture in Europe. The US, NATO, the OSCE and the EU operate on the basis of an existing security architecture rooted in the United Nations, NATO and the OSCE. Under this umbrella, they primarily see room for a new generation of arms control treaties and agreements on previously unregulated areas such as cyber security.

Bilateral preference

Although Biden has tried to coordinate his position with NATO allies and the EU, the emphasis in the week ahead will be on US-Russia relations. Putin prefers bilateral relations anyway – within the EU and even more importantly with the US, thereby bypassing the EU altogether. This week will highlight the near-absence of the EU in the current crisis and the lack of a coherent EU-Russia policy. The political and economic relations of individual EU member states vis-à-vis Russia diverge widely, as does the overall prioritisation of the need for an EU-wide policy towards Russia.

It is inconceivable that NATO will agree to Russia defining the terms of future NATO enlargement policy. The main challenge for the US negotiators and NATO will be to spell out what consequences further Russian military engagement in Ukraine would have. It can be part of a strategy not to provide details on what the response to certain actions will be, but in this case it is necessary to be clear about the type and sequencing of measures in order to disrupt the Kremlin’s step-by-step tactics since the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

New sanctions coming?

The US and the EU need to put forward a coherent message on two sets of potentially painful sanctions: a moratorium on North Stream II – a system of offshore natural gas pipelines in Europe, running under the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany – and a range of financial sanctions, namely against state-owned banks, a cut-off of Russian banks from the Visa and Mastercard payment systems, and the exclusion of Russia from the international financial communication system SWIFT.

Sanctions always also incur costs on the side of those who impose them. Germany has long played down the geopolitical dimensions of North Stream II, and the new German government is internally divided on whether to continue prioritising economic interests over political and environmental considerations. If Russia were to be excluded from SWIFT – similar to Iran in 2018 – domestic and foreign companies and banks, including Swiss ones, would have to make a costly transition to alternative systems, ranging from the one coordinated by the Russian Central Bank (SPFS) to similar systems under development in the EU, China or Iran.

The current challenge for the US and NATO vis-à-vis Russia is to combine credible deterrence with a plan for a de-escalatory sequence of mutually agreed steps. This sequence would link a reduction in inflammatory rhetoric and Russian troop withdrawal from the Ukrainian border with, for example, a temporary halt on military exercises in the Black and Baltic Seas with US, NATO or Russian participation, re-staffing US and Russian diplomatic missions, and renewed Donbas peace talks with a greater role for the US.

The choice of Geneva as the site of the first Biden-Putin summit in June 2021 and for the continuation of US-Russian negotiations on January 9-10 underpins the historic role of Switzerland as a broker in high-stakes international negotiations. However, with regard to relations with Russia, the image of Switzerland being a neutral actor is a myth.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.