The Swiss who fought for change in Nicaragua

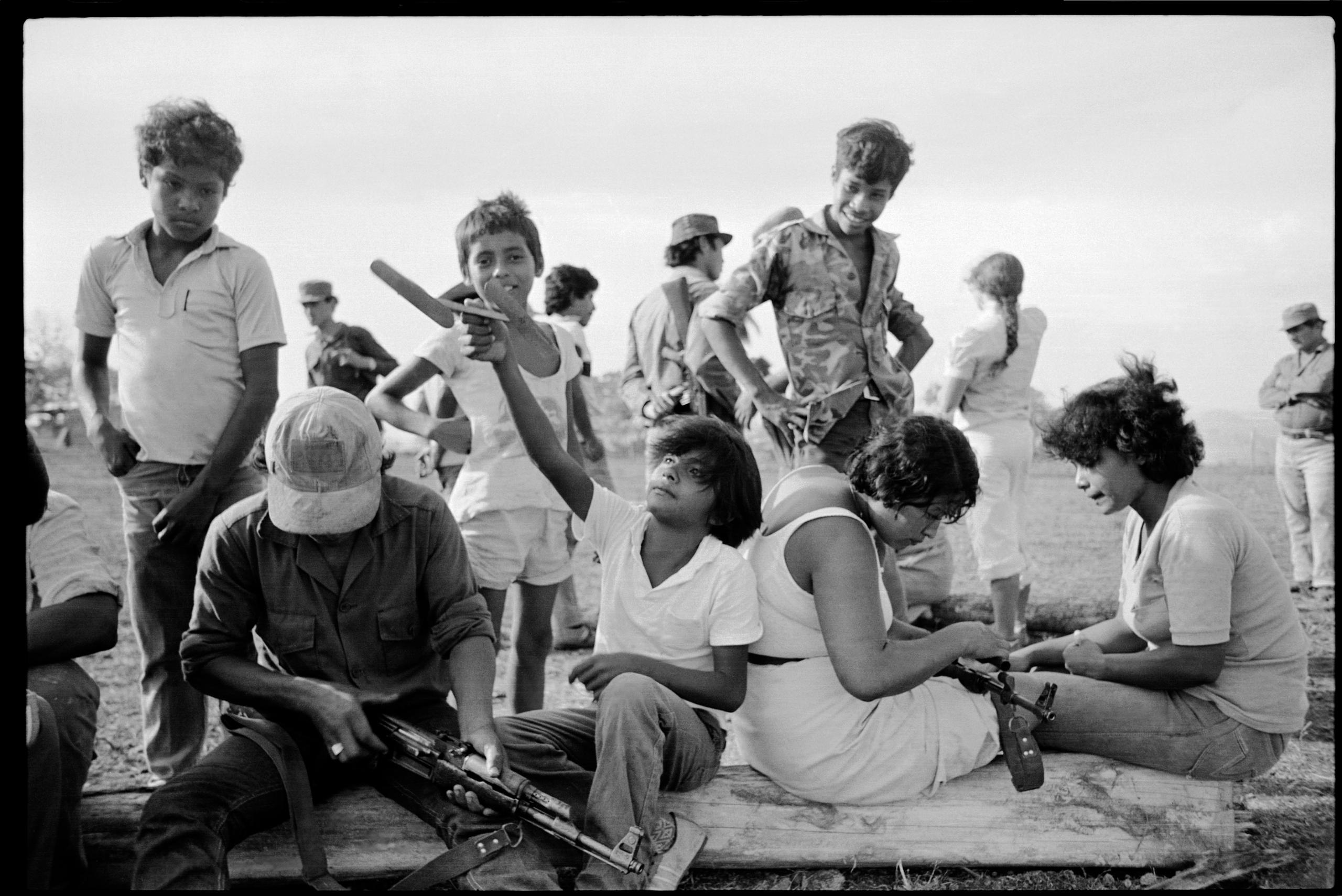

About 800 Swiss volunteered to rebuild Nicaragua after the 1979 Sandinista political uprising against the Somoza dictatorship, and some died in the process. Why did they do it?

“I was fascinated by the idea of living in a country where everything was possible,” recalls Roland Sidler, one such volunteer from Switzerland. “Participative democracy was very well established. The government, the people, the intellectuals, the ideologists, the clergy… all worked together to educate the population, give them shelter and sanitation and to launch agricultural reform.”

International brigades in Spain and Nicaragua

In the 1930s, 40,000 volunteers from more than 50 countries went to Spain to help the Republicans fight against General Franco’s rebels. Around 800 were Swiss, 170 of whom died and 420 were penalised by the Swiss authorities for enlisting in a foreign army. There have since been several efforts to clear their records.

Nicaragua attracted almost identical numbers of Swiss volunteers in the 1980s, although they only served in peaceful capacities. Two Swiss died there. One drove over a mine and another was shot. Thomas Kadelbach, the author of a book on the Swiss volunteers in the Central American country, told swissinfo.ch in 2009 that “The Sandinista Revolution was seen as a battle of David and Goliath, of right against wrong, that of an extremely poor country indirectly attacked by a superpower.”

Thirty years later, Sidler is part of a delegation that has travelled back to Nicaragua to honour fellow volunteers who died there in the 1980s, including two Swiss. They were part of international brigades – groups of pacifist foreigners wanting to help a country revolting against years of rule by a corrupt dynasty.

A maths teacher, Sidler enrolled in an intensive Spanish course. Then, in 1986, he headed to the Nicaraguan capital Managua together with other leftist volunteers.

“We worked in coffee plantations. It was a first for us. They told us to pick the red fruits, but one of us was colour-blind,” he recalls, laughing. “Once, they organised a competition. A young Nicaraguan brought back ten times as much coffee as the rest of us combined.”

More at home working with wood than coffee, Sidler also helped build a community leisure centre in San Marcos, a town near the capital, and spearheaded its becoming a sister city of his native Biel in Switzerland.

“The idea was to create permanent ties,” says his partner Charlotte Krebs. Many such initiatives failed after the Sandinista movement, or National Liberation Front, was defeated at the ballot box in 1990. But she and Sidler kept at it.

“We couldn’t abandon these people who we knew and who continued to work to rebuild the country,” she says. “At this time of uncertainty, we felt an even greater need to actively support these people.”

Through the sister cities initiative, Biel helped San Marcos set up vital infrastructure like power networks and drinking water. In 2014, it helped build a new school with the help of young Nicaraguans and volunteers from Unia, Switzerland’s largest trade union.

A trainee social worker at the time, Krebs gets emotional when remembering the family that welcomed her during her stay in Nicaragua. While living with them, she learned to recognise the signs of an earthquake and how to wash clothes with soap, leaving them to dry in the sun. It also gave her an insight into the mentality of the people, who she says were living every day as if it were their last.

Nurturing the arts

Marion HeldExternal link and Bernard BorelExternal link arrived in the country in 1980 as volunteers for the Swiss non-governmental organisation GVOM. It was one year after the Sandinistas had seized power, overthrowing Anastasio Somoza Debayle and establishing a revolutionary government in its place. Borel had just graduated from medical school while Held was a student at Paris’ renowned Jacques Lecoq theatre programme. It didn’t take long for them to become involved with the respective health and culture ministries in Nicaragua.

In Managua, Held was in charge of training teachers and promoting national culture.

“Before the revolution, there was only the national theatre, reserved for the privileged class,” she says. “Then many troupes sprung up, made up of women, soldiers, students. Everyone loved playing music, dancing or writing poetry.”

With the resurgence of opposition guerrillas who were fighting the Sandinistas and financed by the United States, young Nicaraguans were being called up to serve in the army. As a result, many of these creative troupes were forced to break up or go elsewhere.

Held also created the Triquitraque children’s theatre which performed in parks and neighbourhoods. Using a special acting method, she also managed to encourage blind people to act. She smiles while remembering a popular skit with a blind actor who told his audience that “this neighbourhood isn’t lit very well. You can’t see anything!”

As a country, Nicaragua fascinated Held. “It’s something unique. It was an incredible experience.”

Borel agrees, saying that “this experience influenced the direction of my life”. A volunteer in an extreme left workers’ party, he collaborated with other experts to develop a community approach to child medical problems.

“It was interesting to see the scale of social mobilisation during the vaccination and cleanliness campaign aimed at preventing malaria and dengue fever,” he says. With resources scarce, the volunteers served as staff in villages to help identify illnesses.

Borel remembers doing consultations in classrooms, churches and homes, as well as the generosity of the people, who often gave him fruit when he visited.

What came of his efforts?

“In ten years the infant mortality rate was halved, but living conditions didn’t improve very much,” Borel reflects. “Poverty has stayed the same. But at least people had a vague idea of how to care for children and to ask for help from those nearby.”

Nicaragua’s past

A former Spanish colony, Nicaragua gained independence in 1821.

From the start of the 20th century, Nicaragua increasingly became the subject of US intervention.

US marines occupied the country from 1912 to 1933.

The Somoza clan took over in the 1930s and led the country until 1979.

The Sandinista National Liberation Front seized power in 1979, installing a Marxist-inspired government.

Brutal rebels funded by the US tried to disrupt the Sandinistas’ reforms. Their practices were criticised for human rights violations.

Free elections marked the advent of democracy in 1990, with a coalition of anti-Sandinsta parties winning.

Volunteering is more a part of western life today. Have you had experience volunteering in another country or at home? Would you spend your spare time helping in a country going through major change? Tell us in the comments section below.

Translated by Jessica Dacey

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.