Voting rights: ‘The foreign community is too big to be ignored’

One in three Swiss residents is not allowed to take part in national elections and votes. In most cases that’s because they don’t have Swiss citizenship. How does it feel to live in the country that holds the most referendums in the world without being able to vote?

“I’ve lived in several countries, but my experience in Switzerland is the first time I’ve been directly confronted with a situation where other inhabitants make decisions about my life and my welfare,” says Estefania Cuero, who has an Ecuadorian and a German passport and has lived in Switzerland for four years. “This is very new to me – and sometimes, very unpleasant.”

Cuero, a diversity consultant and doctoral candidate at the University of Lucerne, says specific issues are behind that feeling. “The vote on the burqa ban [passed in March by 51.2% of voters] really affected me. I felt unwelcome – even though I don’t wear a niqab and I’m not Muslim. But for me the message behind it was: ‘We don’t want to see anyone here who looks foreign’.”

More

Swiss ‘burka ban’ accepted by slim majority

The purpose of direct democracy is to involve the population in political decision-making. But regular referendums and people’s initiatives repeatedly reveal who does not belong to the electorate.

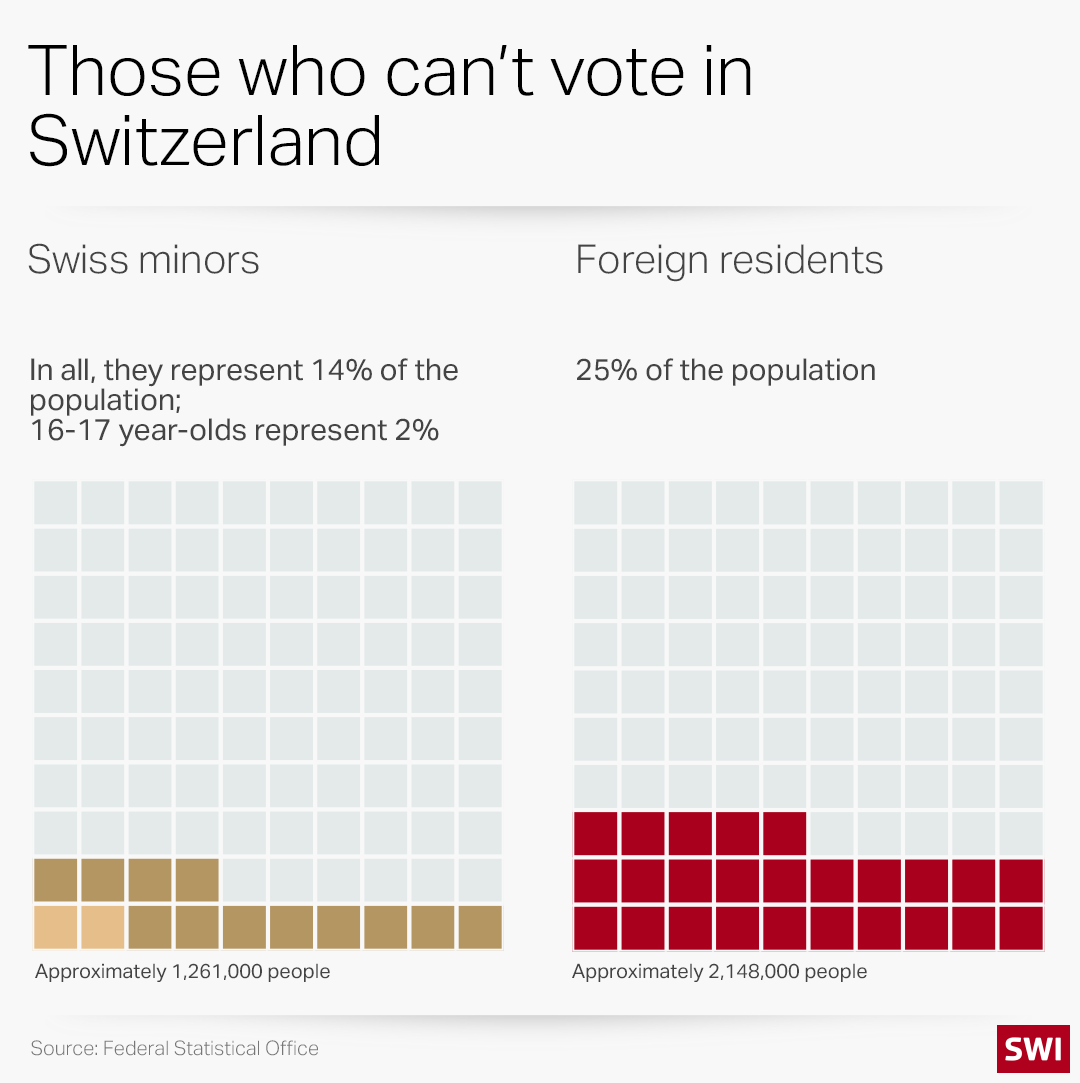

Of Switzerland’s resident population of about 8.7 million, around 35% are not allowed to vote at a national level.

“You often hear ‘Switzerland has voted’ or ‘Switzerland has decided’,” Cuero says. “But if 35% aren’t allowed to vote, then a statement like that is problematic, maybe even wrong. It’s not Switzerland but very specific individuals or a group that can decide for others and therefore exercises power over other groups that belong to Switzerland.”

The biggest group of people excluded from decisions on national issues is foreigners. Switzerland takes the same approach as almost all other countries on this. Only four countries in the world allow non-citizens to vote at a national level: Chile, Uruguay, New Zealand and Malawi. But in Switzerland the question of participation for foreign residents is more pressing than in other countries because the proportion of foreigners is high: roughly a quarter of permanent residents are not Swiss.

This can lead to strange situations. At the 2019 federal elections the municipality of Spreitenbach in northern Switzerland was home to as many adult foreigners as people with voting rights. The electorate accounted for only 39% of the population. What’s more, the turnout in Spreitenbach was very low, so only 10% of all residents took part in the elections.

For a very long time another huge segment of society was excluded from democratic representation: women.

More

The long road to women’s suffrage in Switzerland

“The share of foreign residents has reached dimensions that can no longer be ignored,” says Sanija Ameti, co-president of the pro-European Operation Libero movement.

More

Pro-Europeans rally against isolationists

Ameti was three when her parents fled from Bosnia to Switzerland. When she was young, a number of people’s initiatives, usually launched by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party, concerned migration policy and often stirred up sentiment against the Balkan diaspora.

“My parents and I had no voice in these votes even though we were directly affected by them. It was extremely frustrating, because we had no choice but to put up with the xenophobic and anti-Muslim politics,” Ameti says, adding that this was one of the reasons she entered politics.

“The mass immigration initiative politicised me,” says Hendrik Jansen, who was born, raised and educated in Switzerland. Today he works in public administration and can’t voice his opinion in public, so we have changed his name.

In 2014 Swiss voters narrowly approved a proposal to curb immigration, imposing limits on the number of foreigners allowed into the country.

More

Swiss agree to curb immigration and rethink EU deal

Jansen emphasises that as a Dutchman he has an easier time than other migrants. “People rarely have issues with northern Europeans,” he says. “When I say where I come from, the response is often: ‘You’re one of the good ones!’ But the law doesn’t care about that: a tighter law on deportation, for example, affects everyone without a passport equally.

Voting rights as a means of integration?

Jansen, who is active in clubs and does voluntary work, could vote if he adopted Swiss citizenship. So why doesn’t he? “On the municipal level, at the very least, citizenship shouldn’t be a prerequisite,” he says. “If I’m engaged in society, I should be able to vote.”

He thus addresses one of the key arguments put forward by advocates for foreigners’ voting rights: residents without a Swiss passport take part in community life and pay taxes in Switzerland – why shouldn’t they be able to vote on what happens with that money?

They are directly affected by Swiss laws, so why should one section of the population be denied a say in rules it must obey? At the same time, Switzerland guarantees the right to vote to one group of people who neither pay taxes in Switzerland nor are directly affected by most of the laws: Swiss expatriates.

Even if Jansen wanted to become Swiss, it would take a while. He recently moved – only a few kilometres away, but into a new municipality. That means any application for citizenship would have to wait several years.

More

Why some residents choose not to become Swiss

Ameti, on the other hand, did gain Swiss citizenship and is an active politician in the Liberal Green Party. “I was lucky to be able to apply for citizenship in the city of Zurich,” she says. “The citizenship process is not as fair everywhere – in some municipalities people are subjected to real harassment.”

Ameti thinks the idea of integration via political participation should be revived. The example of Jens Weber shows that this can work.

Weber lives in the northeastern municipality of Trogen, one of the few villages in German-speaking Switzerland that recognises foreigners’ right to vote (see box). As an American, he was elected to the local council in 2006. “It was one of the best days of my life, when I went to Trogen in 2006 and could say ‘right, now I can join in!’” he said in an SWI swissinfo.ch panel discussion. “This experience had a major impact on me and convinced me that I wanted to become a Swiss citizen,” he says.

More

Tell me where you live and I’ll tell you if you can vote

Diversity taken for granted

However, a possible reform of the voting or naturalisation laws is not the only decisive factor in the fair treatment of the many Swiss residents without citizenship.

“What’s needed is an honest discussion about what and who Switzerland is,” Cuero says. “We need Switzerland’s self-image to mirror the diversity of this society.”

“Anyone who insists there is a single defining Swiss culture should explain the Rösti ditch to me,” says Jansen, referring to the linguistic divide between the French- and German-speaking parts of the country. “The Swiss are not all the same. There are differences between them that are not necessarily smaller than the differences between a Swiss person and a foreigner.”

In almost all French-speaking cantons foreign residents can vote at the municipal level and in some cases at the canton level.

In German-speaking Switzerland, by contrast, only foreigners living in some municipalities in cantons Appenzell Outer Rhodes and Graubünden can cast ballots. In some other cantons, such as Zurich, foreigners’ voting rights are under discussion. In canton Solothurn an initiative for foreigners’ voting rights was rejected in December.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.