‘Watch out and hold on to your rights’

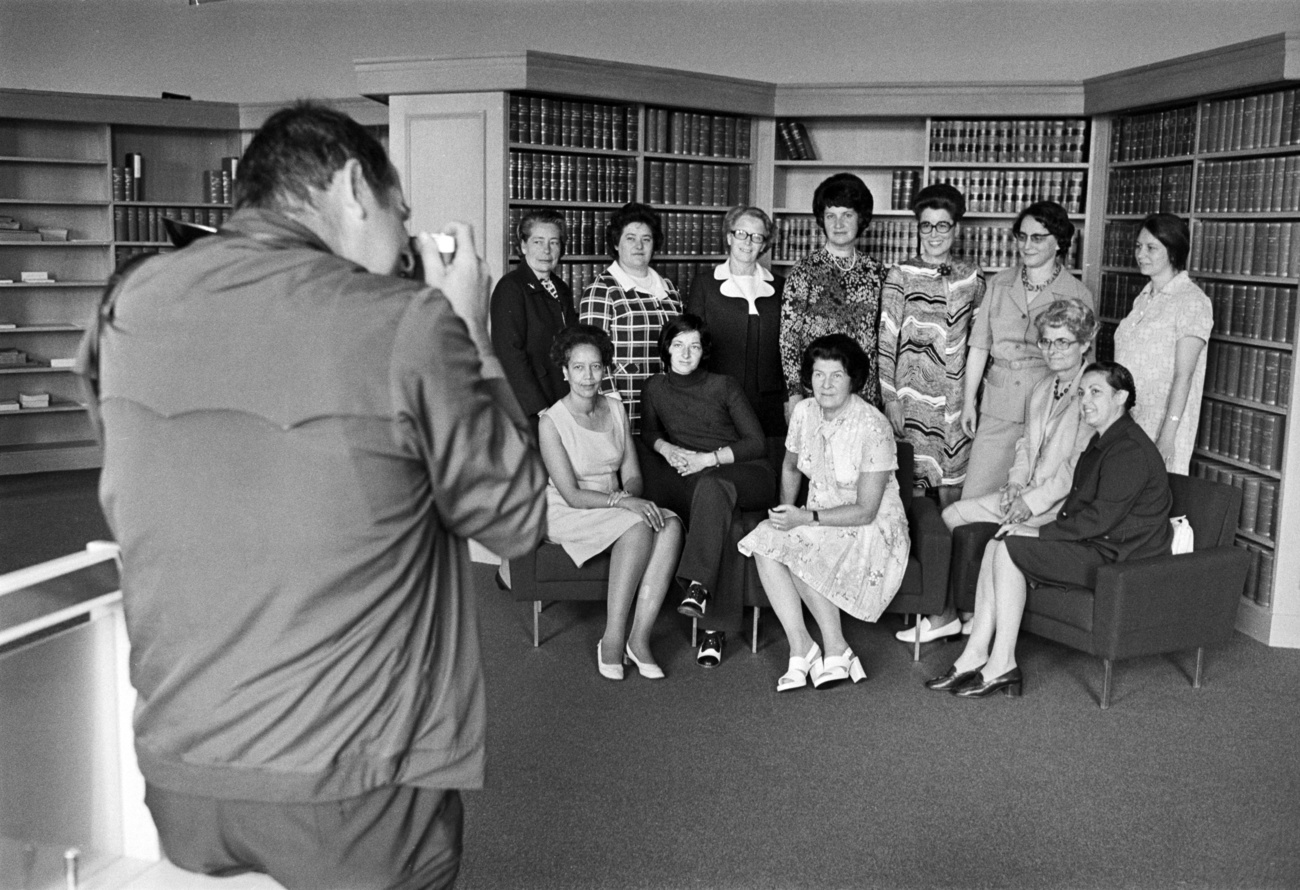

Hanna Sahlfeld-Singer was one of the first women to be elected to the Swiss parliament in 1971. The former Swiss politician looks back at her work for women’s rights and describes how she paid a high price for her campaigning.

Sahlfeld-Singer has lived in Germany for the past 45 years and is arguably one of the prominent Swiss expatriates. This is partly due to her involvement in Swiss politics and women’s suffrage.

On February 7, 1971 Swiss men finally voted to give women full federal voting rights, by a two-thirds majority. Switzerland was the last country in Europe, except for Liechtenstein, to give women the vote.

swissinfo.ch has produced a series of articles, videos and photo galleries to mark this anniversary.

On March 4, swissinfo.ch is organising an online panel discussion on the topic of “50 years after women’s suffrage: old questions of power, new fighters, new successes”. Participants include Marie-Claire Graf, climate activist and UN climate ambassador; Estefania Cuero, specialist in diversity and human rights; and Regula Stämpfli, political scientist specialising in power.

Many people might be shocked to hear about the obstacles that she and her family faced during her time as a politician. But in her interview with swissinfo.ch, the 77-year-old pastor refuses to be bitter about past events.

Memories of the historic vote 50 years ago still brings back strong emotions, as she recounts:

“On February 7, 1971, we were on our way back to Switzerland after a private visit to northern Germany. In the evening we were watching the news on the television in the hotel. Then the news came on: Swiss women get the vote.

My husband and I both shouted with joy. It was then – and still is today – an extraordinary and emotional moment.

It was clear to me that the decision that day would only have limited practical consequences for us at the time. In canton St Gallen, where we lived, women still had no say in local or regional politics. In the Protestant Church women had the right to vote, so I got my first ‘parliamentary experience’ in the church synod.

I don’t remember any specific reaction to the vote from family and friends, or conversations with other women about the subject. My everyday life went on as before, I was busy in my parish, which also included regular visits to people who were sick.

More

As a teenager I was aware that women were discriminated against, as they were excluded and could not take part in decision-making. This was something we also talked about at home.

In my job I experienced unfair treatment. As an ordained minister and a married woman, I was only given temporary or part-time jobs. But my attitude to social and political issues was known publicly, as I had already made speeches on Swiss National Day before 1971. My husband, a pastor with German citizenship, had always passed on to me requests from the local authorities for official August 1 speeches.

So people knew that I was not only able to preach but also to think and have a political opinion.

However, my speech of 1970 was criticised because, instead of singing Switzerland’s praises, I took the liberty of calling for more respect for other opinions. I also demanded the introduction of civilian service for men who, for reasons of conscience, refused to do their compulsory military service in the Swiss army.

More

The introduction of women’s suffrage worldwide

It’s difficult to imagine what it was like for women in those days when compared with the situation now; it’s normal for women to participate in social and political life now.

As a pastor, for example, I was a member of the school committee dealing with handicrafts and home economics lessons for girls. I was happy to do this. But having a say in other matters was impossible and unimaginable for the public and the authorities at that time.

In the run-up to the parliamentary elections of October 1971, the political parties were looking for women to stand as candidates. I had no doubts that it could only be the Social Democratic Party because it had long been committed to equal political rights.

Neither I, nor my husband nor my parents believed that I would be elected. But it was clear to me that if you fight for a cause you have to be prepared to invest in it. That’s why I took part in the election campaign; my costs were limited to a few train tickets.

I heard that men from another political party in St Gallen, the Radicals, tried to prevent my election via legal tricks. They argued that pastors could not be elected to the House of Representatives under Article 75 of the Swiss constitution. The legal provision had been directed against Catholic priests in the 19th century.

It was important for me to show that women could make demands and achieve their goals. The thought that I might actually be voted in – and that this would have far-reaching consequences for my life – was far from my mind.

After the successful election, a solution had to be found so that I could continue to work in my profession. I agreed to work as a pastor without pay, and to take on the duties that pastors’ wives were traditionally expected to carry out.

This meant no more preaching in church, but I could work as a caregiver in the parish and visit patients in hospitals and homes.

More

How the global battle for female suffrage influenced Switzerland

I think my political opponents were less than pleased that we had found a way of fending off their attacks to prevent my election.

The support of my parents and my husband in caring for my children during that time was extraordinary. It was unusual for a father to take on tasks like changing nappies.

On the other hand, my husband’s work situation became increasingly difficult for us. My critics started targeting him, as he was not a Swiss citizen. They looked suspiciously at his work in the parish and the mood became spiteful.

To put an end to the seemingly hopeless situation, we decided that he would seek employment in another parish. But to no avail.

But we still needed a regular income for the family of four. As a member of the House of Representatives, I was only given a small allowance and some of my expenses were reimbursed, unlike parliamentarians today.

The situation became more difficult for me too, even though I spent four years in the Swiss parliament, and I was hugely committed.

I was re-elected in 1975 with a very good result, although the male-dominated trade unions didn’t support me as a Social Democrat.

At the end of the same year I announced my resignation from the Swiss parliament. We moved to Germany, where my husband had found a job in the meantime. It was a decision for my family and for my profession.

All the while, there were rumours that my husband had separated from me and that our modern marriage was unsuitable.

We have lived in Germany since 1976, and I have not been active in (party) politics since. I quickly found a job as a pastor at a high school. I also got involved in development policy, mainly through church projects.

I have continued to follow Swiss politics as best as I could, for example by reading the Neue Zürcher Zeitung newspaper. I also participate – since the option was introduced – in Swiss votes as well as in elections to the House of Representatives.

Did these experiences make me bitter over the past 50 years? Not all; that’s just the way things were.

I was pleased to hear that other women became politically active after my resignation from parliament.

I owe a lot to other women who fought for equal rights before me but were not rewarded. Their commitment was important to me and it is a pleasure to see that many things have improved. Even if we still haven’t reached out goal.

My message to the younger generation is simple: watch out and hold on to your rights. You can fall down the stairs faster than you can climb back up.

It is also important to say that selfish motives should not be someone’s driving force. Sometimes it is easier to solve small problems directly at the personal level. But political solutions are needed for bigger issues.”

Text compiled by Urs Geiser, adapted from German/urs

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.