‘We’re just tenants’: why some foreigners choose not to vote in Switzerland

Portuguese and Spanish nationals living in Geneva and Neuchâtel rarely participate in local elections, despite having had the right to vote for years. A new study provides stark insights as to why.

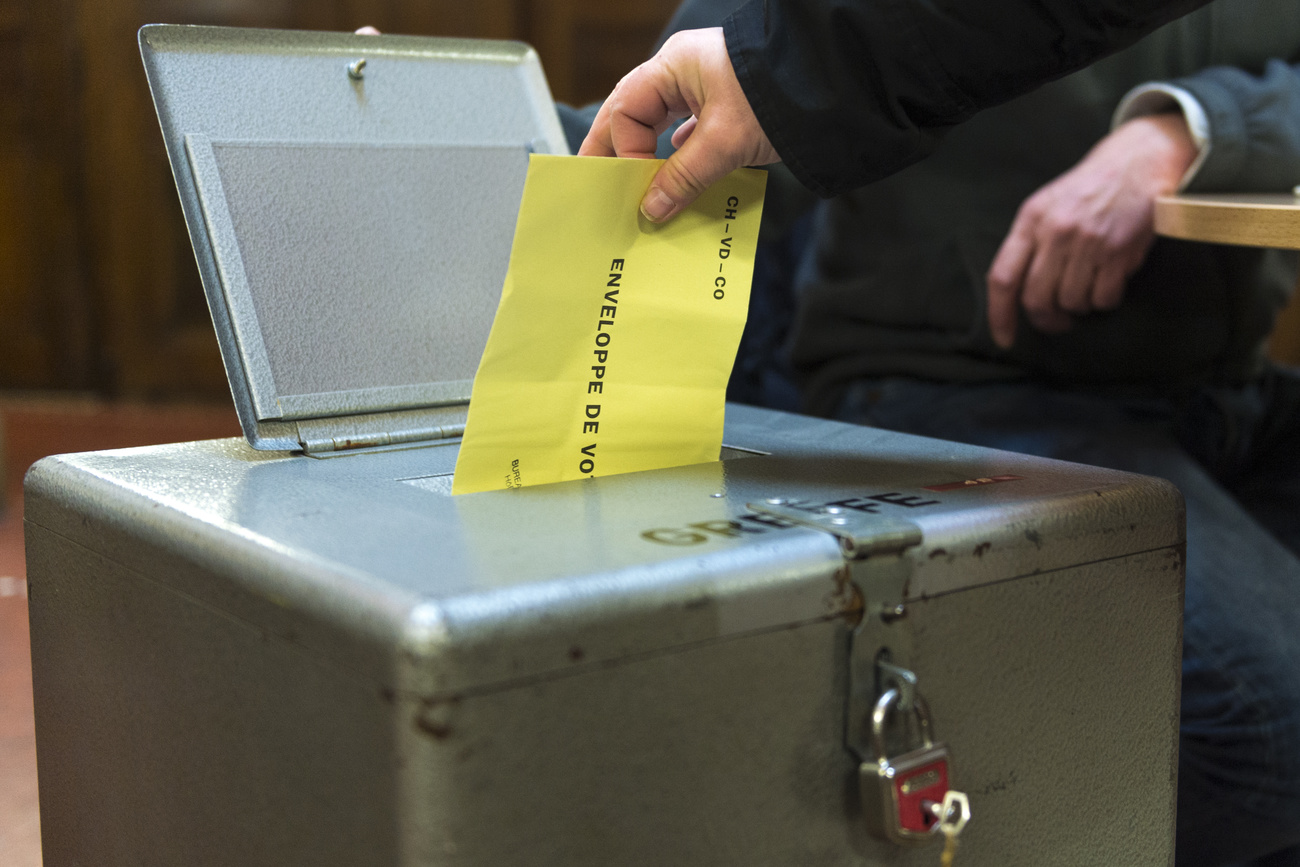

Foreigners make up around a quarter of the Swiss population, one of the highest levels among Western countries. Non-Swiss residents can vote in most French-speaking regions in Switzerland at municipal level and in some cases at cantonal level. But despite having had the right to vote for several years, political participation among foreigners remains very low.

In 2020, around 40% of Swiss voters turned out in Geneva elections, compared with 23% for non-Swiss. Among Spanish and Portuguese residents, the turnout was even lower: 17% and 13%, respectively.

In Neuchâtel, Swiss voter turnout averaged 42% for the 2003-2020 period, compared with 18% for non-Swiss. There are no statistics for individual foreign communities in Neuchâtel, but the overall assessment is similar to Geneva.

Non-Swiss passport holders represent a quarter of the Swiss population of 8.8 million. In canton Neuchâtel foreign residents represented 25% of the total population (176,000) in 2020, compared with around 40% in canton Geneva.

In Neuchâtel, there were around 12,000 Portuguese nationals (7% of the total population) and 2,400 Spanish nationals (1.4%). In Geneva, there were around 33,000 Portuguese nationals residing in Geneva (7% of the population) and 15,000 Spanish residents (3%).

A studyExternal link entitled “We’re just tenants”, released on Thursday by the University of Neuchâtel, took a close look at why Spanish and Portuguese residents in both locations – two non-Swiss communities with the lowest participation – are not using their right to vote. It is based on dozens of individual and focus group interviews with around 100 people who have lived in Switzerland for at least eight years and do not have Swiss citizenship.

“They have a weak feeling of attachment to Switzerland,” concludes Philippe Wanner, a professor at the University of Geneva’s demography and socio-economics institute. “The Iberian communities explain that they do not feel well accepted by the native population.”

More

Foreigner voting rights

His colleague Rosita Fibbi, a researcher at the University of Neuchâtel, agrees. “The people interviewed believe that they are not at home in Switzerland, because they find their situation unstable. Their lease and employment contracts can be terminated at any time. They are the targets of discriminatory attitudes. This disappointment leads them to consider a return to Spain or Portugal when they reach retirement age,” she told Le Temps newspaper.

These feelings are compounded by a strong attachment to their country of origin, she noted.

Attitudes vary over time and depend on people’s socio-economic situation. Among the first generation of Spanish and Portuguese to settle in Switzerland, electoral participation is higher among those who already had experience of politics, who originated from cities, or who have a good level of education, the researchers found.

Among their descendants, electoral participation is limited. Recent immigrants, however, tend to show a greater interest in voting. They also have a higher average level of education than people who immigrated in the last century. Participation is less among those working in international organisations or multinationals, who have relatively little contact with the local population.

‘Voting is useless’

But generally, the first generations of immigrants to Switzerland arrived with the idea that “voting is useless”, said Fibbi.

The transition to democracy in Portugal and Spain in the 1970s and 1980s did not lead to fundamental changes in their lives. “This feeling of helplessness persists here,” said the Neuchâtel researcher. “If at the collective level nothing evolves, then the only lever for action is to work hard to improve one’s individual condition.”

And such attitudes have simply been passed on to the next generation. Their children vote as little as their parents, the researchers note. “In Spain and Portugal, people vote for political figures, here we debate more on issues,” said Fibbi, adding that Swiss politics is seen as complicated.

More

Switzerland – a two-tier democracy

The study proposes ways to increase the communities’ involvement in society, and especially in political life. Their recommendations include improving public recognition of Portuguese and Spanish communities in society, promoting unconventional experiments in political participation, particularly through citizens’ assemblies, and providing better information on voting issues. Extending the electoral rights of foreigners is also an issue.

Grégory Jaquet, the delegate for foreigners for canton Neuchâtel, admitted that the study results were severe and held up a “cruel mirror”, but he said the migration narrative must move from talking about “them” to “us”. He also called for foreigners’ electoral rights to be extended.

More

Election candidates with ‘foreign’ names face discrimination, says study

Where can you vote locally in Switzerland?

At the national level, only Swiss citizens aged 18 and above are allowed to vote and to stand for election. In some cantons and municipalities, however – especially in French-speaking Switzerland – foreigners have certain political rights.

Two cantons in French-speaking Switzerland – Neuchâtel and Jura – allow foreigners to vote in cantonal elections and ballots, under certain conditions. In Neuchâtel, they must have a permanent residence permit and have been living in the canton for at least five years; in Jura they must have been living in Switzerland for at least ten years and in the canton for at least a year.

At the local level, French-speaking Switzerland is again more open: foreigners are entitled to vote in municipal elections and ballots in Neuchâtel, Jura, Vaud, Fribourg and Geneva. The conditions vary from canton to canton, but in most cases a certain length of residence or a permanent residence permit are required.

In the larger German-speaking part of the country, only the cantons of Basel City, Graubünden and Appenzell Outer Rhodes authorise their municipalities to allow foreign residents to take part in local votes and elections. Only some of the municipalities in question have, however, introduced this possibility. In May 2023 Zurich parliament narrowly turned down a proposal by city officials to grant local voting rights to non-Swiss passport holders in Switzerland’s most populous canton.

In total, foreigners can participate politically in roughly a quarter of the 2,100 municipalities in Switzerland.

Proponents argue that giving foreigners voting rights makes society more democratic and more inclusive.

Opponents say foreigners should obtain the right to vote and stand for election at all levels via the naturalisation process, as is currently the case. An attempt to grant foreign residents full voting rights at national level was thrown out by parliament in June 2022.

More

Who can vote in Switzerland? Who can’t?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.