What it takes to be a UN human rights chief

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet announced in June that she will not be seeking a second mandate. She said this was because she wanted to spend more time with her family and was not related to her recent controversial visit to China. But what will be her legacy, and what is required of her successor?

“Michelle Bachelet came to the position with her unique outlook as a victim of human rights violations, an activist and a stateswoman,” says Jürg Lauber, Switzerland’s ambassador to the UN in Geneva, where the human rights office is based. “While highlighting human rights violations throughout the world, she has built bridges, engaging in dialogue and offering cooperation.”

Bachelet is a former President of Chile (2006-2010 and 2014-2018) and was the first elected female leader in Latin America. She was detained under the Pinochet regime and her father died in one of the dictator’s jails after suffering daily torture.

She became UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in September 2018. Her four-year mandate ran through the Covid-19 pandemic and major human rights crises including in Myanmar, Yemen, Afghanistan, Ethiopia and South Sudan, with the war in Ukraine breaking out early this year. It was tarnished near the end with a much-criticised visit to Xinjiang province in China.

“Her office was extremely responsive in promoting a human rights-based approach to addressing the Covid crisis and its consequences,” says Lauber. He told SWI swissinfo.ch that Bachelet has also been a “strong advocate for addressing the challenge of climate change, poverty and inequality”.

Phil Lynch, director of the Geneva based NGO International Service for Human RightsExternal link (ISHR) agrees that Bachelet has played an important role on these issues, as well as migration, systemic racism and promoting vaccine equity in the context of Covid-19. But he is critical of her approach to country situations where he says she has “privileged friendly dialogue with governments over what we would say are the interests of a consistent, non-selective, principled approach to dealing with human rights crises”.

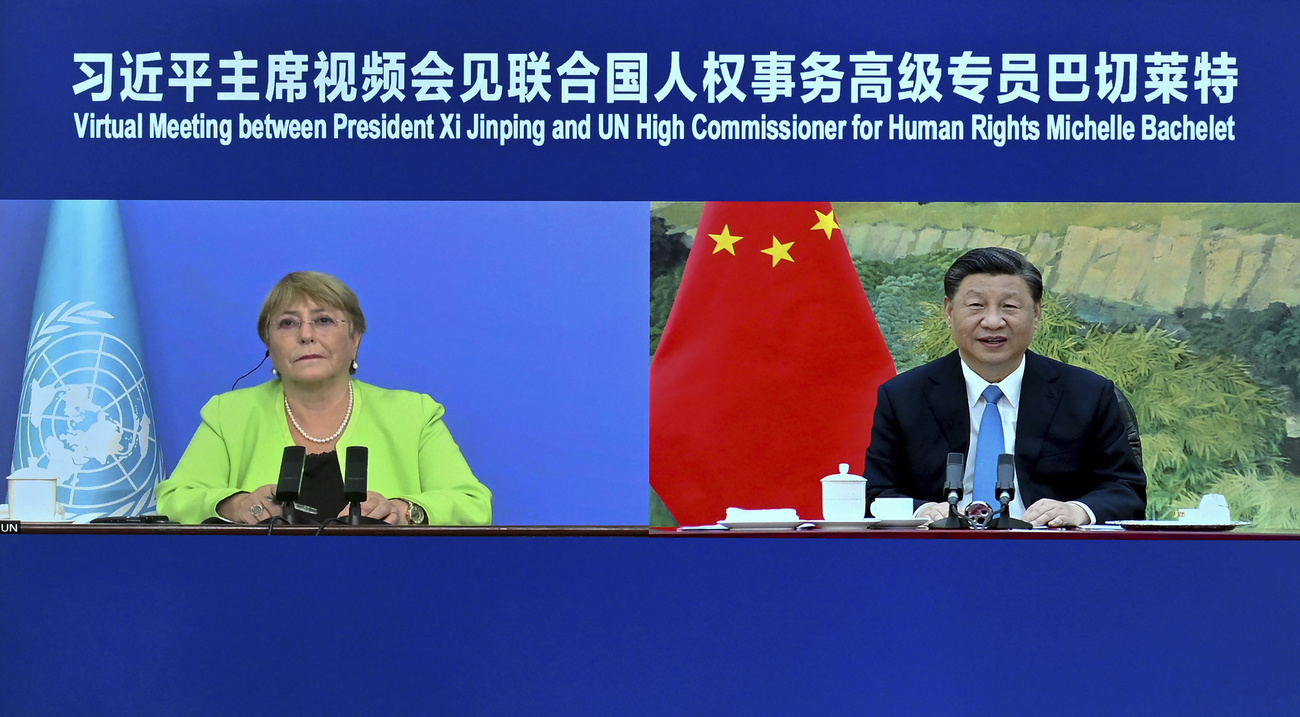

The China visit

The most notorious example, he continues, is on China “where she has wholly failed to address the human rights situation in the country, including crimes against humanity in Xinjiang, as well as widespread repression in Tibet and Hong Kong, enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention of human rights defenders and lawyers across the country”. Lynch says Bachelet’s approach on China has demonstrated a “marked lack of solidarity with victims or human rights defenders and an inability or an unpreparedness to hold a powerful government to account”.

Bachelet’s visit to China at the end of May, when she was accused of being too compliant with Beijing, was much criticised by NGOs like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, as well as some States. They have also slammed her for withholding publication – perhaps because of the China visit — of a potentially explosive UN reportExternal link on human rights violations in Xinjiang province, where Beijing has unlawfully detained some one million members of its minority Muslim Uighur population, according to many credible reports. Beijing says the detention camps are for re-education and training, and denies allegations of torture, forced labour and other abuses.

More

UN rights chief in China: walking a tightrope between engagement and risk

“It’s hard to ignore the China visit that came right at the end of her mandate,” says Sherine Tadros, Amnesty International’s Deputy Director of Advocacy and head of its UN office in New York. “I think that has clouded her legacy, it’s what will essentially follow her around and how she will be remembered.”

Tadros told SWI that Bachelet was “definitely at the forefront and very engaged” on economic, social and cultural rights and her office produced a strong report on Venezuela, which Amnesty International applauds. But her approach on the China visit was damaging. “I think if you are a family of one of the victims, or a survivor of the camps, it’s very difficult to ever forget her words sitting there in China and talking about training camps, adopting the propaganda language of the government,” she told SWI. “That’s incredibly damaging. And I’m not sure how you repair that.”

Lynch agrees. “Of course, dialogue, cooperation and technical assistance are important and legitimate ways to advance human rights where there is political will, but where the violations are institutionalised, widespread or indeed part of government policy, as is the case in Xinjiang, then what is vital is monitoring, reporting and holding to account,” he told SWI.

The report

Announcing her departure at the start of the just-ended Human Rights Council session in Geneva, Bachelet said she would release an updated version of the Xinjiang report, which will be submitted to the Chinese government for comments, before she leaves office at the end of August. Can she still redeem herself on China?

“We’ll have to see what the report says and whether the input of the Chinese government, which she allowed again at the end, will tone down what we understood to be quite a strong report,” says Tadros. “Because the evidence on the ground, as documented by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and many others, is very strong and persuasive.”

‘Missing in action’?

Lynch thinks Bachelet has also been “missing in action” on some other country situations, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Venezuela, where he says her assessment of human rights reform has been “overly rosy”. She also did not consult or engage with civil society “to anywhere near the extent” that some of her predecessors like Navanethem Pillay of South Africa or Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein of Jordan did, adds Lynch.

Khalid Ibrahim, director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights, agrees. He says many human rights defenders have been jailed during Bachelet’s term in countries like Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, and that “she did very little to improve the human rights situation in our countries”. He also laments a lack of accessibility for human rights groups like his own.

Ibrahim admits that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has a tough job, but thinks Bachelet spent too much time talking to States and not enough with civil society. If you want to be the voice of the voiceless, “you need to listen to defenders in the field, you need to know what’s going on”, he told SWI.

Search for a new High Commissioner

A United Nations spokesperson in Geneva said in mid-June that the recruitment process for Bachelet’s successor was underway, and that UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres would submit the next UN High Commissioner for Human Rights for approval by the General Assembly, once a suitable candidate was identified. An announcement would be made in “due time”.

More

Who will take on the United Nations’ toughest job?

How important is this position, especially given the political constraints? “It’s vital. It is the voice of the human rights community,” says Tadros of Amnesty International. “I think that it’s an incredibly hard job, just like the job of the UN Secretary-General. No one is taking away from how delicate it is to have to negotiate with States on the one hand, seeking access and keeping your own staff safe, but on the other hand speaking truth to power and exposing what’s going on in different countries. It’s a really difficult balance, but it’s one that Bachelet got wrong.”

Swiss ambassador to the UN in Geneva Lauber says that any person coming into the position of High Commissioner for Human Rights needs to show a “strong commitment to the promotion and protection of human rights worldwide and have the necessary gravitas to engage dialogue with all States”.

Lynch thinks it takes even more: “We consider that the role of the High Commissioner is to be a human rights champion. It’s to be the world’s leading human rights advocate and defender, as distinct from the role of a diplomat or political envoy.”

Calls for a ‘transparent’ process

More than 60 NGOs, including ISHR, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, sent an open letterExternal link to UN Secretary-General Guterres in June calling for a “transparent, merit-based, consultative process” to pick the next High Commissioner for Human Rights. “It should involve wide and meaningful consultation with independent human rights organisations and human rights defenders,” they say. “Given that High Commissioner Bachelet’s mandate will end on 31 August 2022, it is imperative that this process move quickly.”

“It’s important to recall that the post of High Commissioner was a civil society initiative,” says Lynch. “It was civil society which, in the lead up to the 1993 Second World Conference on Human Rights, identified the need for, and the importance of having a global human rights leader and champion to advance human rights worldwide.”

“There has to be consultation with civil society,” says Ibrahim of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights, which signed the letter. He says his organisation is fed up with UN High Commissioners being selected “behind dark doors”. Neil Hicks, senior advocacy director of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies which also signed, agrees. “We would like civil society publicly included, so the international community can see that the UN will go out of its way to ensure that human rights organisations and civil society have a voice in this process.” He says this would be an important recognition of their role, particularly at a time when they are at risk of being “stamped out” in many parts of the world including the Middle East and North Africa.

“What we have right now is a job advert that we can all see online to apply for the position of UN human rights chief,” says Amnesty’s Tadros. “We don’t know anything beyond that. We don’t know who’s applied, what the real criteria are, if it’s a real process or just one of those box-ticking exercises.”

Edited by Imogen Foulkes

More

Inside Geneva: What does it take to lead the UN human rights office?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.