What’s the best way to distribute asylum seekers in Europe?

Migration expert Etienne Piguet and his team at the University of Neuchâtel in western Switzerland have mapped out what a balanced distribution of asylum-seekers in Europe could look like.

Back in 2015 the record influx of refugees to the European continent crudely highlighted the gross imbalance between countries receiving the bulk of asylum claims – namely Greece, Italy and Spain – and those whose doors remained firmly shut.

The recent fire at the Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos has only renewed interest in the issue. Just days after the disaster, the European Union presented its New Pact on Migration and Asylum, its latest effort at reforming the system for the 27-nation bloc.

The pact, released on September 23, takes stock of the failure of the introduction of quotas after the 2015 migration crisis. Among the main proposals are:

- Introducing a pre-entry screening procedure to identify at an earlier stage those asylum-seekers who have the least chance of obtaining international protection

- Reviewing the Dublin regulation, which currently gives responsibility for processing a claim to the country reached first by the asylum-seeker, to broaden the criteria for determining which country should process the claim

- Creating a “mandatory solidarity mechanism” to which all states have an obligation to contribute based on their economic wealth and population size. To avoid resistance from certain countries in accepting asylum-seekers, this contribution could take the form of supervising the return of rejected applicants or offering logistical support.

Piguet, a geography professor, laments the fact that it took “reception conditions on the Greek islands to become intolerable for us to make a little bit of progress”.

Together with his team, the expert in migration policy decided to map what could be a fair distribution of refugees in Europe from a quantitative point of view.

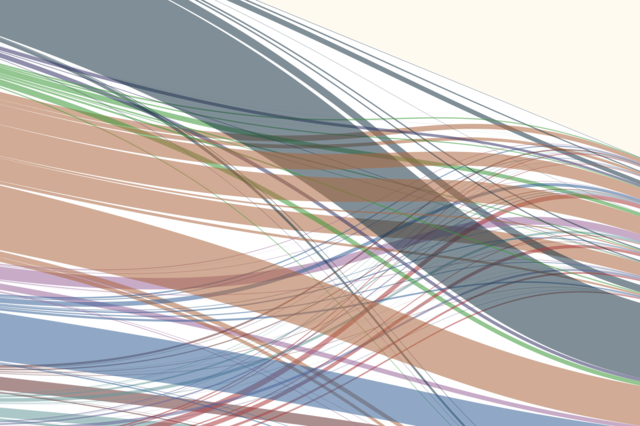

The interactive version of this project, which began in 2014, juxtaposes the number of asylum-seekers received by each country since 2008 (red semi-circles) with the number that would be considered “equitable” (grey semi-circles) based on a set of criteria. And there are political stakes in choosing just which criteria should determine where asylum-seekers end up in Europe.

Gap between theory and reality in asylum distribution

Population size is the most popular factor used to determine the number of asylum-seekers that a country should accept. In fact, it is the distribution key used to allocate refugees across cantons in Switzerland.

According to Piguet’s map, the Alpine nation received 14,200 asylum applicants in 2019. But based on population size alone, it ought to have taken just 11,800.

By this same demographic calculation, Greece has welcomed a surplus of asylum-seekers, as have Sweden, Germany, Belgium, France and Spain. By contrast, in addition to Eastern European countries, Portugal, Norway, Denmark and the United Kingdom have all received numbers far below their capacity.

For distribution to be truly equitable, however, some experts argue that additional factors should be taken into account – such as the country’s surface area, wealth, and the state of its labour market.

To go back to the Swiss example, if we were to take wealth instead of population size as the distribution key, then the country should have welcomed more than 27,000 applicants for asylum.

This, evidently, is an extreme example of the distribution theory. The geography institute at the University of Neuchâtel uses a study by the Mercator Foundation as its reference point. It suggests allocating a weight of 40% to GDP and population size, and 10% to unemployment rate and surface area. Based on this reasoning, Switzerland ought to have received 5,000 more asylum-seekers than it did in 2019.

Switzerland doing ‘just enough’

The tool shows that since 2008, some countries have been either consistently open or consistently closed to asylum-seekers, while others have alternated between the two. Switzerland falls into the latter category, although in the last five years it has generally fallen into the “closed” camp.

“Switzerland is doing enough to not lose credit, but not more than that,” said Piguet. “It is being careful not to be seen as one of the countries in Europe that are closed, but it’s not explicitly showing itself to be especially proactive. There is a contrast between its humanitarian tradition […] and its policy, which is to just do its part.”

There are political negotiations involved in choosing which factors or criteria should be used to decide where asylum-seekers go.

“The goal is not to propose a distribution that would be just, but to provide basic information,” said Piguet.

He believes it’s important to set objective criteria for managing migration – not only in order to prevent certain countries from avoiding their obligations, but also to encourage public support.

More

Why Swiss cities can’t yet take in Moria refugees

Difficult negotiations underway

That’s why he has both “cautiously” and “rather positively” welcomed the new EU migration pact, which has been roundly criticized by NGOs, who say the EU is kowtowing to anti-immigrant governments by leaving them the possibility of not accepting refugees.

“I think we can’t really expect a more satisfactory outcome than what’s been proposed,” said Piguet. “We have to offer exit options for countries [that are little or not at all prepared to welcome refugees] so they won’t block the project to the point of ruining it.”

The negotiations on the pact are already proving difficult. The most resistant among the Eastern European countries have already indicated that they would oppose any forced relocation of refugees to their territories. EU officials expect the project will not be finalized before 2021.

“Switzerland salutes the global approach taken by the new pact to meet migration challenges,” said Justice Minister Karin Keller-Sutter, who took part in a virtual conference of European interior ministers in October. According to the Federal Department of Justice and Police, Switzerland is now reviewing the proposals for legislative adaptations, notably to determine which aspects fall under the scope of the Dublin and Schengen agreements to which it is party.

More

We agree with the EU on one point – we must get out of this dead end

Adapted from French by Geraldine Wong Sak Hoi

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!