The risk Switzerland runs with referendums

British politicians on both sides of the Brexit campaign cast this summer’s referendum as a once-in-a-lifetime chance for voters to have their say on a defining issue for the nation. In Switzerland, such opportunities are rather more frequent.

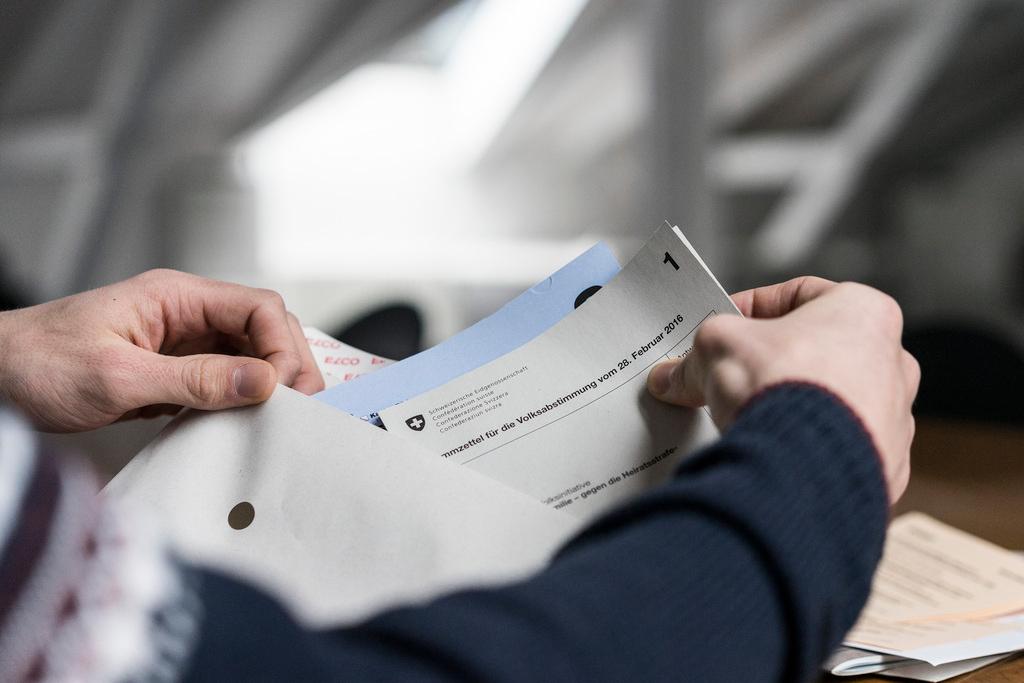

In the past ten years, Swiss citizens have been asked to opine with increasing regularity on issues as disparate as executive pay, tax policy and – most sensitive of all – immigration. On Sunday, they will go to the polls again, to vote on a new tunnel through the Alps, a ban on “speculation” in commodity trading and controversial proposals on the expulsion of foreign criminals.

Such “popular initiatives” have always been part of the Swiss system, with any group of citizens able to propose a change to the constitution if it is supported by 100,000 signatures. In recent years, however, populist parties on both sides of the political spectrum have found it to be a convenient tool to bypass parliament and force more radical ideas on to the agenda.

Corporate leaders worry that this extravaganza of direct democracy is starting to threaten the country’s image as a stable, predictable, open place to do business.

Voter trends

When it comes to proposals with a direct bearing on the economy, their fears are probably exaggerated. Voters have proved remarkably level-headed: they did not support proposals from the hard left to impose an unrealistically high minimum wage or add an extra week to their holiday allowance.

More

Financial Times

External linkThey also proved willing to listen to the arguments made by policymakers and business lobby groups on more technical issues, rejecting a proposal that would have forced the Swiss National Bank to keep a fifth of its reserves in gold. A vote to limit executive pay-offs was a valid reaction to flagrant cases of corporate excess.

Immigration, however, is a different matter. As early as 2009, voters supported a ban on the construction of new minarets. Two years ago, they backed the imposition of quotas on immigration, a decision that has thrown Switzerland’s relations with the EU into disarray.

The ultranationalist Swiss People’s party (SVP), responsible for bringing these issues to a vote, has since re-inforced its position as the country’s most powerful political party. In Sunday’s vote, polls suggest that the proposal to toughen rules on foreign criminals – so that even someone with a couple of speeding fines might face automatic deportation – has at least a chance of passing.

Business leaders are right to speak out against this trend. The rise of anti-immigrant sentiment threatens their ability to recruit; and could do far-reaching damage to Switzerland’s image as an open economy at the heart of Europe.

Officials are still battling to find a way to reconcile immigrant quotas with Switzerland’s commitments to free movement of labour to and from the EU. Access to the single market could be under threat, with implications for multinationals’ willingness to base themselves in the country.

It is clear that, when it comes to the emotive issue of immigration, economic arguments are a secondary consideration for voters. The rise of SVP mirrors that of populist parties in Europe, and politicians elsewhere should not be tempted to dismiss Switzerland’s populist turn as a quirk of its unique system.

Many Swiss officials are dismayed at the choices voters have made in recent years but they still feel the system is an accurate expression of their wishes. Less so, however, when direct democracy is being hijacked by populists.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2016

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.