When the Swiss franc had to learn to float

In 1973 the gold standard was finally abandoned and exchange rates lost their stability, the consequences of which were also felt in Switzerland. Two historians discuss this upheaval.

At the beginning of 2023 the Swiss National Bank (SNB) reported a record deficit of CHF132 billion ($143 billion). It accumulated this in its fight against the appreciation of the franc because, among other reasons, it had to buy foreign currencies to counteract a run on the Swiss currency.

The Swiss economy’s strong dependence on the SNB is historically new. It began in January 50 years ago, when Switzerland had to say goodbye to fixed exchange rates.

More

Why can’t the Swiss National Bank go bankrupt?

Historians refer to the years after 1945 until the mid-1970s as the “years of the economic miracle”. The end of the boom is fixed to a specific date: the collapse of the Bretton Woods international monetary system.

The Bretton Woods Agreement, which was adopted by 44 countries at a UN conference in 1944, aimed to minimise international currency fluctuations. On the one hand, it fixed the ratio of the dollar to gold. On the other, all nations undertook to stabilise their currency through their monetary policy – in particular the buying and selling of dollars.

After all, international monetary policy after 1945 was characterised by the desire for stability and predictability. For economic historian Tobias Straumann, Bretton Woods was a kind of prolonged war economy. “After the First World War, people very quickly returned to the liberal economic order of the 19th century – which ended with the great crash of 1929. After the Second World War, people were therefore more cautious and delayed the transition to a peacetime economy.”

But this system crumbled in the late 1960s. The US could no longer maintain the promise of being able to redeem every dollar in gold. In 1971 President Nixon abandoned the gold standard.

For Straumann, that was the most decisive point in the history of money. “Since then there has only been printed paper. You can get into debt indefinitely,” he said. “The link to the precious metal had previously restricted this.”

Swiss reputation

Switzerland had strongly advocated this monetary system of fixed exchange rates since the 1960s.

In 1962 Max Iklé, then a member of the SNB governing board, stressed that he was also concerned with correcting Switzerland’s reputation. Surely everyone had already noticed “that our banks, with their large international business, were being looked at with sceptical eyes by their foreign competitors”, he said, adding that even the American president referred to Switzerland as a tax haven.

“Wealth is also an obligation in monetary policy,” he said.

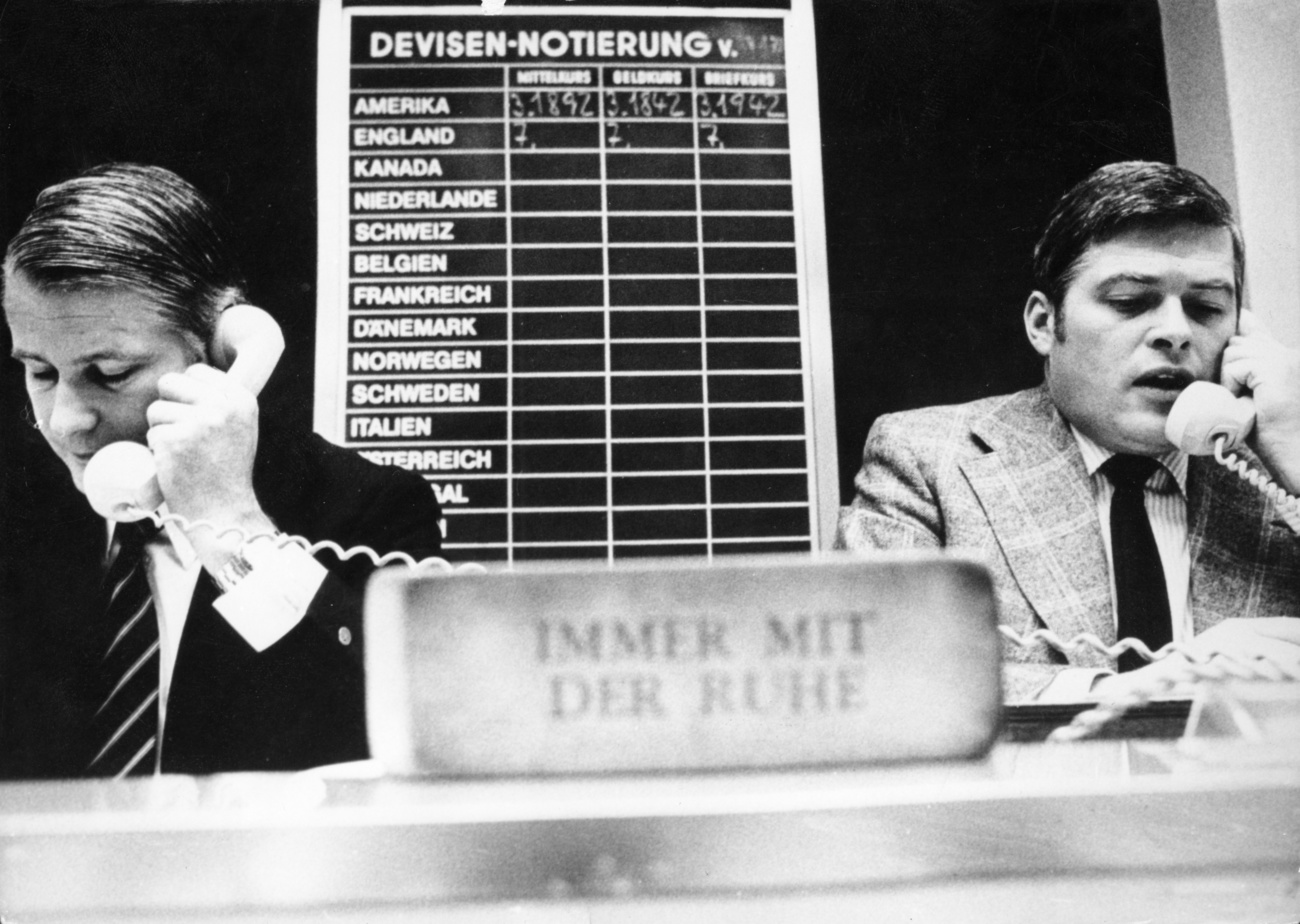

However, at the end of January 1973 Switzerland broke away. A currency crisis in Italy had again led to an investor stampede for the franc. Swiss Finance Minister Nello Celio announced that the SNB would not buy any more dollars for the time being and would leave the franc to the market.

The franc was no longer stabilised by buying and selling dollars. In doing so, Switzerland also heralded the end of the post-war monetary order – it was the first country to let its currency float.

Snake in the tunnel

It would be wrong to assume that this was the result of major strategic considerations. Both the government and the national bank assumed that dollar purchases would be suspended only for a short time, and then resumed later. As late as 1971 the then president of the SNB, Fritz Leutwiler, considered flexible exchange rates to be simply “utopian”.

Even when the transition to this was a done deal, he told a colleague that he had “no idea how to do monetary policy under flexible exchange rates”. But Leutwiler became a specialist in warding off capital flows into Switzerland.

“They were doing something they didn’t want to do and had to improvise all the time,” Straumann said.

In fact, the SNB itself was not convinced about going it alone. As early as 1975 it considered joining the European Exchange Rate Association, the so-called snake in the tunnelExternal link, a system of European monetary cooperation aimed at limiting fluctuations between different European currencies.

“For them this was something of a training camp for the euro,” said Jakob Tanner, professor emeritus of history at the University of Zurich. “This is where the idea emerged that the only way to get around the uncertainties of floating was to abolish exchange rates within a stable bloc, which was solidified in 1979 with the European Monetary System.”

But accession failed because of France, which wanted to prevent a bloc of hard-currency countries around the German mark, and not least because criticism was levelled at banking secrecy.

Consequences for export industry

Switzerland had knocked on the Europeans’ door because its franc had drastically increased in value as a result of its release – with consequences for the export industry.

From 1970 to 1980 employment in the industrial sector in Switzerland shrank from 40% to 32%. The fact that there was no mass unemployment was only due to the exodus of foreign labour and the dismissal of women in part-time jobs. The trade unions held the new monetary policy primarily responsible for the downturn.

It would be wrong to claim that Switzerland has therefore become a deindustrialised zone over time: the share of manufacturing companies in gross domestic product (GDP) is now just over 25%, ahead of Germany (24%), Italy (22%) or France (16%).

But the high exchange rate of the franc has changed the production structure of industry. “In Switzerland the industries that survived were mainly those that were able to escape the fierce price competition,” Tanner said. “If a manufacturer in the Bernese Oberland produces valves with cutting-edge technology, it’s not so central if their price doubles because they are used in machines that cost millions. Quality and international service are more important.”

Straumann takes a similar view. “Continuous upward pressure on value forces the economy to specialise and innovate,” he said. At the same time, however, he sees a danger that “we will end up producing only luxury products, such as watches and specialised pharmaceutical products.”

‘Huge responsibility’

However, the SNB did not operate entirely without a concept. In 1974 the SNB began forecasting the total money supply for the next year. “This provided a certain anchoring. You provided money for economic growth,” Straumann said.

But the franc continued to rise dramatically. In 1975/76 Switzerland’s GDP fell by 7.15%, a world record even in the crisis-ridden 1970s. Then in 1978 the franc’s value shot up 30% against the dollar in nine months.

“[US economist Milton] Friedman underestimated how much exchange rates fluctuate. They thought the market would then adjust exchange rates nicely. They didn’t expect the swings of the 1970s,” Straumann said.

More

Is Switzerland a currency manipulator?

At first they wanted to resort to old recipes such as controlling the capital flowing into Switzerland, but that had little effect. Not only did the dollar weaken, but also the German mark, which had long been a reserve currency for the franc.

The SNB had to find new ways and communicated a directive for the first time. German marks were bought with francs and the price was shifted via demand. What was new was that a lower limit was communicated – “the goal was once again to get more than CHF0.80 per German mark”, Straumann said. Until the foreign exchange traders accepted it. A minimum exchange rate was introduced and defended with currency purchases – a strategy that was later used repeatedly.

Floating was accompanied for the first time by the possibility of an autonomous monetary policy. This made the SNB a decisive player in an area where parliament had no say.

“There are, of course, good reasons for an independent central bank,” Tanner said. “It prevents it from becoming a pawn of associations and special interests. But since the transition to floating exchange rates, the SNB has gone from being a small exclusive club to a large organisation with its own research department. It assumes a huge responsibility for the entire economic policy. Therefore, it would have to be made democratically accountable. Independence does not preclude that.”

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Translated from German by Sue Brönnimann

More

Should the Swiss National Bank distribute more money to the government?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.