Will Puerto Rico become a new US state in 2025?

In November 2023, Puerto Ricans may vote on whether they want to become the 51st US state or gain full independence. Washington – for the first time ever – has signalled a possible green light to allow for a binding vote.

In one of its last sessions in 2022, the outgoing United States House of Representatives approved a bill providing Puerto Ricans a binding referendum to be held in November this year. The referendum will offer voters the choice of statehood, independence or a “free association” with the US – similar to the cases for the Marshall Islands and Micronesia.

Two hundred and thirty-three members of the US lower chamber of Congress voted ‘yes’, while 191 were against. This historic bill is now awaiting passage to the Senate, where it needs at least 60 ‘yes’ votes from the 100-member chamber. The same referendum procedure last occurred in the 1950s, when the people of Alaska and Hawaii were asked whether they wanted to become US states.

Until 1898, Spain ruled Puerto Rico, which then became a “commonwealth territory” of the United States; a hybrid status which did not grant Puerto Ricans voting rights. As of today, and in spite of gaining citizenship in 1917, Puerto Ricans are unable to vote in federal US elections, and do not have a voting representative in Congress in Washington.

The island is hoping that the upcoming referendum may soon determine how it wants to be governed. Unlike previous votes, this one approved by Congress will be binding.

More

Does your vote count? Trump says ‘Let’s see’ – Switzerland says ‘Let’s talk…’

A formula that no longer works

“Puerto Rico in its current state is a colony of the United States,” said Milagros Martínez, a political activist in Puerto Rico. “That formula no longer works in this country.”

She hopes the referendum may lead the island to become an independent state.

Martinez manages a project to assist fishermen in one of the areas worst hit by the recent tropical cyclone, Fiona, in Puerto Real in the southwest of the island. A recent series of natural disasters as well as the pandemic, has highlighted how the dependence had affected the economy and aggravated vulnerabilities on the island.

The island is regularly hit by Atlantic cyclone activity. Five years ago, hurricane Maria caused widespread damage to communities, crippling the entire power grid and causing at least 2,975 deaths.

Puerto Rico has always received a lower rate of federal funding for basic medical insurance, known as Medicaid, than any state of the US. A spiraling debt crisis that led to a default and deep economic downturn added to challenges. “There were hits, one after the other,” Martínez told SWI swissinfo.ch.

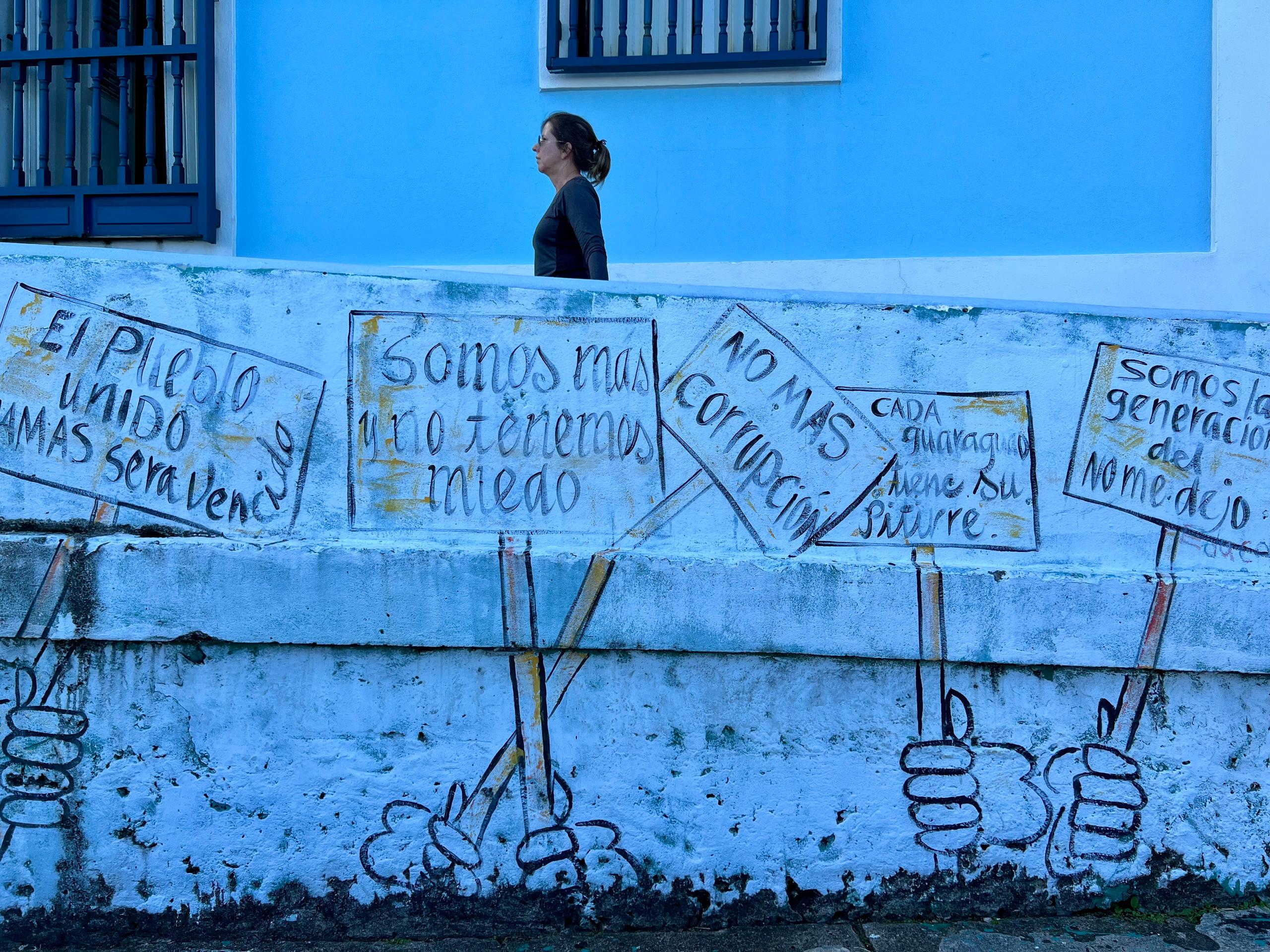

Political activism for change

A growing awareness of the limitations of the current status, coming from greater community involvement amid insufficient preparedness and response to the climate disasters by federal authorities and local government, has aroused political activism.

Protests in 2022 against the US-Canadian electricity company Luma, which runs the island’s power grid, and illegal construction by foreign-owned companies on public beaches have come as popular statements against the perceived cosiness between local officials and US authorities and businesses.

“We need an oversight board that works. We do not need an oversight board imposed by Congress,” Deepak Lamba Nieves of the Center for a New Economy, a think tank in San Juan, said at a panel in September organised by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter University in New York on decolonising disaster response efforts.

Across the United States and in other countries, the success of referendums to access or to separate from a country often boil down to the constitutional and statutory framework of how the vote is organised: recent examples include the 2014 Scottish independence vote, which was pre-approved by the UK parliament as binding; 55% of the voters said “no” to an “independent” Scotland. A similar wish for a popular vote by the Catalan government was not approved by the Spanish government in 2017. As a consequence, the non-binding referendum led to violence and criminal prosecutions. In Switzerland, where referendums are frequent features of the political system, the example of the separation of French-speaking canton Jura from canton Bern was successfully (and mostly peacefully) conducted over more than two centuries.

From non-binding to binding referendum

Six non-binding referendums have been held over the past 50 years asking about possible statehood. In the most recent one held in November 2020, 52.5% of Puerto Rican voters said the island should become the country’s 51st state. The vote, not approved by Congress, was boycotted by many political movements in Puerto Rico. It nonetheless confirmed earlier trends rejecting the status quo.

“People go and vote and express their opinion. Then usually there is a report in Washington with the results, and usually that is where it ends,” said Ada Torres, a Puerto Rican history researcher at the University of Chicago. As a result, she said, a certain voter fatigue may have set in: “There is not very much interest from the Puerto Rican people to lead another non-binding, inconsequential referendum.”

Jenniffer González-Colón, the island’s only representative in Congress, expressed her own frustration with the current situation as she presented the Puerto Rico Status Act in Congress: “We cannot vote for the president who sends our sons and daughters to the war. Because we are a territory, the federal government can, and often does, treat us unequally under federal laws and programmes. We are treated as second-class citizens. Because we are a territory, I am here to discuss a bill related to one of our most critical issues, and yet, I cannot vote on this bill.”

‘Historic’ negotiations in Washington

With Republicans taking control of the lower chamber on January 3, it is possible that the bill may be buried before it is formally transferred to the Senate. Such a move would mean that the referendum planned in 2023 would face the fate of others before it and be non-binding.

While some Republican representatives such as Liz Cheney have been supportive of Puerto Rico becoming a state, other representatives like Bruce Westerman, another leading Republican, argue that the legislation was discussed in a “hasty and secretive process”.

There is a general perception that Puerto Rico could sway towards Democrats if given statehood, though a 2019 Politico poll found that the largest number of Puerto Ricans, 42% of the population, said they weren’t committed to either of the two major parties.

González-Colón, a Republican, told SWI that negotiations through Congress were “historic”. Talks, she said, allowed parties “to agree that the territorial status status-quo, being the problem, cannot be the answer, and that Congress had to clearly define the constitutionally viable, non-territorial status alternatives.”

More

Moutier: the Swiss conflict that has been ongoing for more than 200 years

Towards independence – instead of statehood?

In Puerto Rico, the push for independence has been rising in recent years. After a 2018 Washington Post poll showed only 10% favoured independence, the 2020 gubernatorial election had two parties supporting independence and decolonisation, attracting more than a quarter of the vote.

Others however may see joining the US as a state as a more secure option, providing access to much needed federal funding and social protection programmes, as well as voting rights and proper representation in Congress.

González-Colón, who favours statehood, said that the two sides nonetheless agree on a common point: “The true advocates of independence and statehood in Puerto Rico have always been very clear on their positions and on the failure of the status-quo to enable the progress of Puerto Rico, and understood that it has to end, that the true enemy is colonial stagnation.”

Even in this fishing town of Puerto Real, there is the sense that the vote could not come sooner. Carlos Rodríguez, the president of the local fishermen’s association said regular power cuts made worse by hurricane Fiona have limited the storage capacity for the daily catch, reducing his ability to provide members with a regular income.

With few job alternatives available for the fishermen, few of whom had completed their basic schooling, the future is bleak. “The fisherman always has to defend himself. Government help needs to be faster. No one is concerned about us and there is no one in Washington to represent us,” he said.

Edited by Virginie Mangin

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=f05a5a9c)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.