Aid officials urge tougher stance to end targeting of hospitals

Deliberate attacks on health facilities, aid workers and patients in war zones must be condemned more strongly to prevent them becoming the ‘new norm’, warn humanitarian officials and diplomats in Geneva.

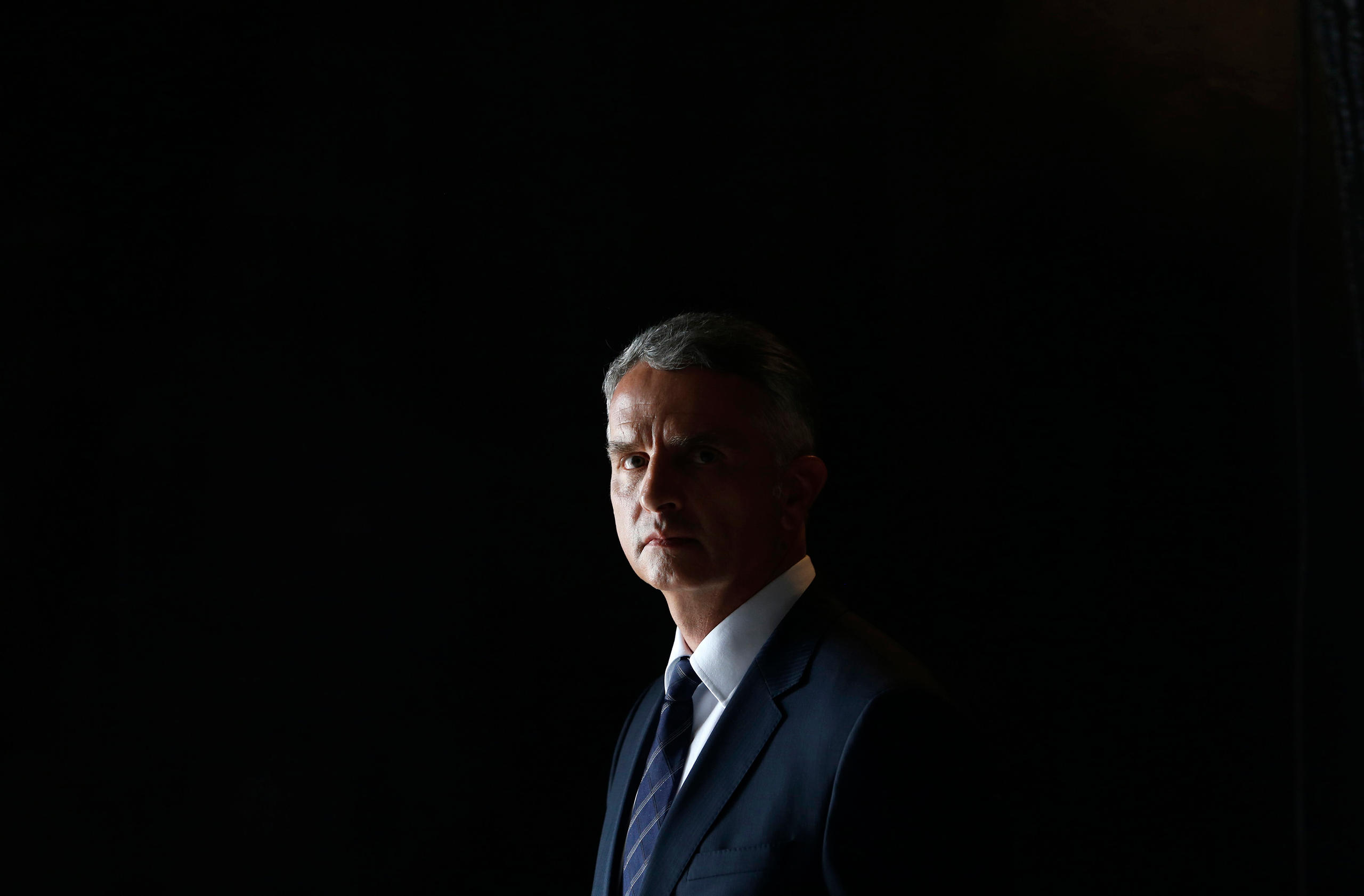

“Initially, I thought it was perhaps a mistake. When we indicated where the hospitals were located they were targeted 2-4 times. We thought about putting a UN flag on them but we were begged not to as people said they would be even easier to be targeted. In some hospitals, the warring parties had lots of weapons stored underground,” Staffan de Mistura, the special United Nations envoy for Syria, told a gathering of humanitarian officials and diplomats in Geneva on Monday.

“To a certain degree, everyone [involved in the Syrian conflict] has decided to use hospitals as an instrument of war.”

De Mistura made the remarks on Monday at a special event at the UN’s European headquarters to mark World Humanitarian DayExternal link on August 19. The annual event aims to raise awareness of aid work, commemorate workers who have died while in the field, and mark the day in 2003 when 22 people were killed in a bomb attack on UN offices in Iraq, including the head of mission Sergio Vierra de Mello.

This year, humanitarian organisations were particularly vocal in their criticism of attacks against aid workers and health care facilities.

Deadly duty

So far this year, 82 aid workers have been killed and 64 have been wounded or kidnapped, according to the Aid Worker Security Database (AWSD). Last year, 288 aid workers were targeted in 158 attacks that left 101 dead, 98 wounded, and 89 kidnapped.

“Most of these attacks unfortunately were clearly intentional and deliberate. They don’t simply happen by mistake. What we observe is a conduct of war and military strategies that purposely aim at depriving services and taking away hope,” said Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) Director-General Bruno Jochum.

“The trend is also to criminalise medical services. Some countries, such as Syria have forbidden doctors to give medical care to wounded opponents or made it a reason for punishment. In too many cases it’s the very act of providing care which is targeted and this brings questions – is there still space for humanitarian action in conflicts?”

Marco Baldan has worked as a war surgeon with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) for the past 20 years in difficult contexts such as Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Yemen and South Sudan. He is shocked by what he has witnessed in the past few years.

“The recent killings of six local ICRC staff in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the destruction of hospitals in Yemen are not inevitable consequences but choices combatants make,” he told the audience. “We have a choice. We can let them happen with impunity and turn our backs, or we can muster up the courage and say as war surgeons, humanitarians, diplomats and human beings that it doesn’t have to be this way. Patients, doctors and ambulances are not a target.”

Last year, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 2286External link calling for greater protection of health care and humanitarian aid in armed conflict and strengthened accountability for perpetrators of attacks. But humanitarians present in Geneva felt too little had been done to implement it.

“We need to bring words and actions together,” said ICRC Vice President Christine Beerli.

Canadian ambassador Rosemary McCarney described the unanimous resolution as ‘essential but insufficient’. She urged states to be much more offensive to condemn violations of international humanitarian law: “We have to be very vocal and reject any view that what is going on in Syria, for example, is the new norm.”

On Monday, Dr Rebecca Dali, the Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian NGO Centre for Caring, Empowerment, and Peace Initiatives (CCEPI) was awarded the 2017 Sérgio Vieira de Mello award in recognition of her humanitarian services for women, children, orphans and vulnerable people who have been affected by the activities of the Boko Haram militants in northeastern Nigeria. In particular, Dali has helped promote the re-integration of returning women abducted by the Boko Haram group back into their local communities.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.