Yemen and the challenge of Covid vaccine rollout in conflict countries

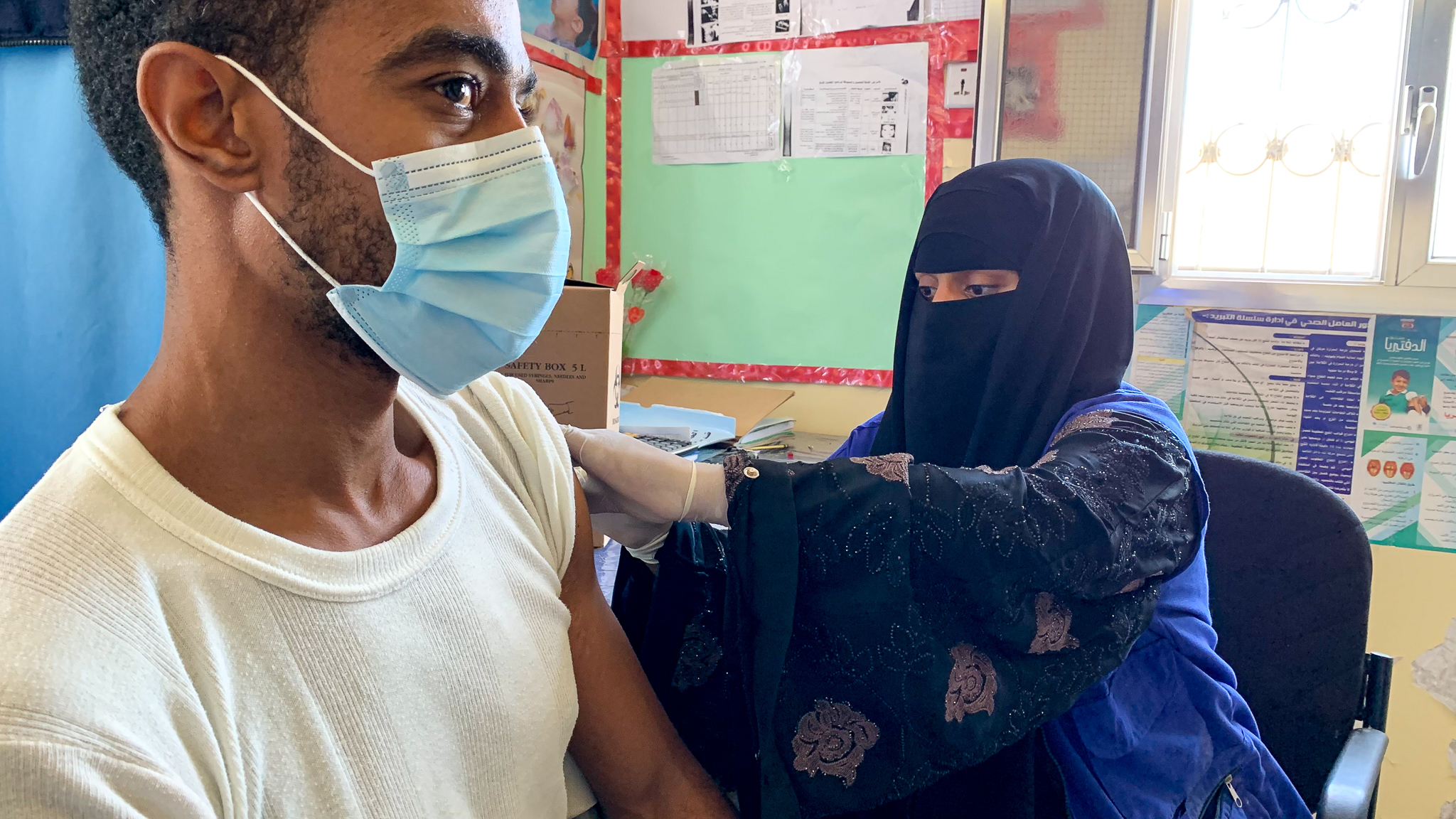

The UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) has recently started supporting the Covid-19 vaccine rollout in Yemen. The challenges of bringing these vaccines to conflict countries like Yemen are enormous.

Yemen received 360,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine through the World Health Organization’s COVAX vaccine pool on March 31, and rollout of the vaccination campaign began on April 20. “It is extremely important that all vulnerable communities in Yemen have access to the Covid-19 vaccine,” states an IOM press releaseExternal link. “IOM welcomes the Government of Yemen’s decision to take an inclusive approach to the vaccine rollout by including migrants in need.”

In a country that has been torn apart by conflict for more than six years, with water and health facilities damaged and one of the highest rates of malnutrition in the world, much of the population is vulnerable. There are also an estimated 4 million internally displaced people and at least 32,000 stranded migrants, mostly from Ethiopia and Somalia trying to get to Saudi Arabia. “Yemen is already the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, and the Covid-19 pandemic has just compounded the situation,” says Olivia Headon, IOM Media and Public Relations Officer for Yemen.

Challenges

The IOM is offering five of its existing health centres in the country as vaccination points, and IOM doctors have been trained to administer jabs. These centres are mainly in areas where there are many displaced people, but vaccination is also offered to the local population, according to Headon. She says this initiative will be expanded to more centres “depending on demand and whether the doses can reach those locations”.

Just getting the vaccines to the centres is extremely difficult, she explains. “Getting anything into Yemen is a logistical challenge. And you’re also working with different authorities in the north and in the south. Different agreements have to be made to get them into the country. That’s the first challenge, and then getting them to the health centres, because there are over 40 active front lines in Yemen. Usually any route you’re going to take will be unsafe.”

Security is of course a big issue in any conflict country. One of the IOM vaccination centres is in Ma’rib, some 170 kilometres northeast of the capital Sana’a and only a few kilometres from a frontline in the conflict. “So at any time, the operation could be under threat and stopped because of safety concerns,” says Headon. “The health workers in Yemen are on the frontline in terms of the Covid response, but also putting their lives at risk working so close to conflict as well.”

Vaccine reluctance

Another big challenge is vaccine reluctance amongst the war-weary population, which may feel Covid-19 is the least of their worries. This goes hand in hand with a reluctance for people with Covid-19 to come forward and go to hospitals. This contrasts with the previous cholera epidemic where symptoms were much more visible and easily recognisable (watery diarrhoea, affecting particularly children). As a consequence, recorded Covid-19 cases in Yemen are still low compared with other countries, but evidence on the ground suggests the virus’ spread has been spiking since March in a second wave, according to Headon.

Vaccine reluctance is fuelled by distrust of the authorities and the outside world. “After six years of conflict you feel like you’ve been left behind by the world,” says Headon. “So you are sceptical of some things that are coming from the outside or how they are being handled inside.” She says vaccine scepticism has been fuelled by the local media, adding that IOM and the UN are working to give people the “right information”.

Similar concerns have been found in other conflict regions. For example, vaccine hesitancy is cited as one of the reasons for the DR Congo’s decision to return 1.3 million COVAX vaccine dosesExternal link, saying it cannot roll them out before they expire in June. People’s hesitancy has been fuelled by concerns over blood clots, but also stems from lack of trust in the authorities and a feeling that Covid-19 is less of a threat than other diseases like Ebola and measles. In DRC too, misinformation about the vaccine has spread on social media.

Supply problems

A fundamental issue is, of course, the supply of vaccines. Yemen has received a first batch of 360,000 AstraZeneca doses, which is part of 1.9 million doses it is supposed to receive in 2021. Given the current threats to supply of this vaccine, in part due to the Covid-19 crisis in major producer India, they might not arrive. And even if they do, “this still leaves millions vulnerable to the virus and Yemen nowhere near herd immunity”, Headon points out. The 1.9 million doses (required in two shots) are for a population of nearly 30 million people.

WHO director general Tedros Ghebreyesus recently called the current shortage of vaccines for poorer countries a “scandalous inequity”, while UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres also called for more international solidarity on vaccine delivery.

More

In the vaccine race, can COVAX help poorer countries catch up?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.