Bunkers for all

Switzerland is unique in having enough nuclear fallout shelters to accommodate its entire population, should they ever be needed.

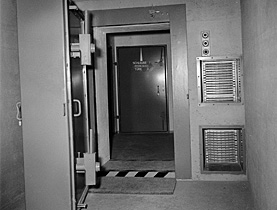

“Why on earth have you got a reinforced steel door in your cellar?” The amazement of a visiting Italian friend is easy to understand. He has never been in the basement of a Swiss home.

Cellar? Well, the room is half full of bottles of wine, old books, a freezer, unwanted clothes… but a cellar it certainly is not. Our friend has simply stumbled upon our fallout shelter. Thanks to the thick armoured door and the ventilation system, with anti-gas filter, if the worst came to the worst, the 25 or so tenants of our block could survive even a nuclear strike.

These Swiss! Paranoid and obsessed with security, our friend must have thought. And there is probably some truth in that assessment.

The Swiss do in fact spend more than almost any other nation (more than 20 per cent of their budget) to insure themselves against everything and everyone. But there is a more simple reason: it is a legal requirement.

More

Nuclear fear

Room for the whole nation

“Every inhabitant must have a protected place that can be reached quickly from his place of residence” and “apartment block owners are required to construct and fit out shelters in all new dwellings”, according to articles 45 and 46 of the Swiss Federal Law on Civil Protection.

This is why most buildings constructed since the 1960s (the first regulations on the subject were passed on 4 October 1963) incorporate a fallout shelter.

In 2006, there were 300,000 shelters in Swiss dwellings, institutions and hospitals, as well as 5,100 public shelters, providing protection for a total of 8.6 million individuals – a coverage of 114 per cent.

World champions

The Swiss are undoubtedly world champions in the construction of shelters. A quick international survey is enough to demonstrate that no other country can rival it.

The closest are Sweden and Finland. But with 7.2 and 3.4 million protected places respectively (representing approximately 81 per cent and 70 per cent coverage), they are still far behind.

The situation in other European countries does not even compare. In Austria, for example, coverage is 30 per cent, but most of the shelters do not have a ventilation system. In Germany, the national level of coverage is a mere three per cent.

Outside Europe, fallout shelters are common in China, South Korea, Singapore, India and elsewhere, but nowhere does coverage exceed 50 per cent. In Israel, there are shelters for two-thirds of the population, but in many cases these structures are simply concrete shells with openings, therefore not completely fallout-proof.

The golden age

When the systematic construction of fallout shelters began in Switzerland in the second half of the 1960s, it was a reflection of widespread fear of a nuclear strike and the spectre of a Soviet invasion. “Neutrality is no guarantee against radioactivity,” was one of the slogans of the time.

More

Why bankers go bonkers for bunkers

For some years, Switzerland could also boast the largest civil defence project in the world: up to 20,000 people could take refuge in the Sonnenberg tunnel in Lucerne.

On the seven floors above this tunnel, inaugurated in 1976, were a hospital, an operating theatre, a radio broadcasting studio, a control centre… However, the infrastructure, dismantled in 2006, was deficient in several respects. The doors, for example, 1.5 metres thick and weighing 350,000 kilos, did not close properly. And the builders had overlooked a couple of details: the logistical and psychological problems such a large concentration of people would be prone to.

“No change of policy”

With the end of the Cold War and a new security situation, many countries introduced radical changes in policy. In Norway, for example, in 1998 the authorities revoked the regulations on the provision of bunkers.

But in Switzerland, there was no such rethink. In 2005, member of parliament Pierre Kohler submitted a parliamentary initiative that would have removed the obligation to provide shelters in private dwellings. He stressed the pointlessness of these “relics of the past”, which inevitably pushed up the cost of building residential accommodation.

However, after analysing the situation, the government came to the conclusion that they were still useful, not only in the event of armed conflict, but also in the light of possible terrorist attacks with “dirty weapons”, chemical accidents and natural disasters. So the future is still bright for Swiss fallout shelters.

In 2006 Switzerland had about 300,000 nuclear shelters in homes, institutions and hospitals, with about 7.5 million places, as well as 5,100 public shelters (1.1 million places).

The annual costs for the construction, maintenance and demolition of the shelters amounted to SFr167.4 million in 2006. Of this, SFr 128.2 million were borne by private persons, and the rest by the communes (SFr 23.5 million), the Confederation (SFr 9.8 million) and the cantons (SFr 4.2 million). The total value of the shelters is put at SFr11.8 billion.

Building a shelter in a private house costs about SFr10,000 ($9,370). People having a house built are not obliged to include a shelter. If they decide against one, they must instead pay their commune SFr1,500 for each place in a shelter, calculated at two places for every three rooms.

Between the introduction of this regulation in 1979 and 2006, communes took in about SFr1.3 billion, and paid out SFr750 million for the construction of public shelters. The remaining money has not yet been used. The government wants to halve the compulsory payments.

People who have shelters are allowed to use them for other purposes, such as storage space, but are obliged to keep them in good order. In recent years some public shelters have been used as temporary accommodation for asylum seekers.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.