President Ignazio Cassis: a man who resembles Switzerland

Who is Ignazio Cassis, Switzerland’s new president? Known for ending talks with Brussels on the European Union institutional framework agreement, he hopes to achieve consensus in his new function. SWI swissinfo.ch takes a deeper look at the man who will represent Switzerland in 2022.

His father Luigi Cassis was a farmer; and his grandfather an Italian immigrant who settled in a village near the border in Ticino. “If you grow up with three sisters and one bathroom, you learn how to negotiate,” Ignazio Cassis declared about his humble origins. He was an unruly child. At the age of 12, he lost the little finger of his right hand on the spike of a fence that he fell off.

Now, at the age of 60, Ignazio Cassis has become the president of Switzerland. He is a typical product of the Swiss militia system, which is now elevating him to this honorary position. In 2017, after a swift ascent through party politics, he entered the Swiss national government. His roots in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland helped him; the minority canton had not been represented in the government for a long time. His open, uncomplicated manner worked in his favour. In many ways, Cassis is a man who resembles Switzerland.

The toughest portfolio

Once in government, Cassis took on the most difficult portfolio. With no diplomatic experience, he was in charge of unjamming Switzerland’s blocked relations with the European Union and negotiating a framework agreement to oversee long-term ties with Brussels.

That failed. In 2021, the Swiss government broke off negotiations. The decision was reached by the seven-member cabinet, but the disappointment it caused was mainly focused on Cassis. Swiss foreign policy experts were critical, and in a Swiss Broadcasting Corporation opinion poll last autumn, Cassis was ranked lowest of all the members of government.

“My goal is not to be popular but to do good work,” Cassis declared in an interview with Swiss public television SRF. “It is more important to stay true to my principles and implement my policies.” As a representative of the Radical Liberal Party (FDP), he is a political liberal. Observers place him on the right wing of his party.

A doctor in government

After the unspectacular conclusion of negotiations with Brussels, the Swiss presidency appears as a light at the end of the tunnel for Cassis. Liberated from the EU portfolio, can he establish himself as a unifying figure and take the stage in the pandemic as a doctor and expert?

This is a possible optimistic scenario put forward by some Swiss newspapers. Cassis was awarded his doctor’s diploma at the University of Zurich at the age of 26. He then became a young cantonal doctor in canton Ticino before doing his doctorate as a specialist in public health. He told SRF recently: “With my background I can definitely explain the government’s decisions to people.”

Ignazio Cassis came to politics late in life. He first took office at the age of 43 in the assembly of his local municipality of 4,600 inhabitants. At 46, he became a member of parliament. “He was not a politician, but we saw him as a good candidate,” recalls Fulvio Pelli, a veteran FDP leader who has supported Cassis from the beginning of his career. “He is an intelligent man and he is quick to learn.”

The Swiss president is neither the head of state nor the head of government. The seven-person cabinet, also known as the Federal Council, is considered a collective head of state and government. The president might be “primus inter pares” – the first among equals – but he or she doesn’t have any greater power than the rest of the cabinet. Each of the seven cabinet members takes it in turn to hold the ceremonial one-year rotating post. The unwritten rule is that the presidency passes to the government member who has not held it for the longest time.

First steps as a diplomat

In a sense, Cassis is just chairing government meetings and fulfilling particular representational duties. He holds a radio and television addresses at New Year and on the federal holiday on August 1. In addition, he welcomes foreign diplomats in Switzerland at a New Year’s reception. It is also common practice for the federal president to undertake official visits abroad.

None of this is new territory for Ignazio Cassis. He has served as Swiss foreign minister for four years and in that role he is now at home on the diplomatic scene. It wasn’t always so. His first steps on the international scene were tentative.

Cassis took over the Swiss foreign ministry in November 2017. As a health politician, he had all the necessary knowledge for the interior ministry, but the only open position was that of foreign minister. In Switzerland, this ministry doesn’t make big waves in domestic politics. Development aid and diplomacy take a longer-term view. “Foreign policy isn’t very popular in Switzerland,” says Pelli. “No one wants the foreign ministry. He took it.”

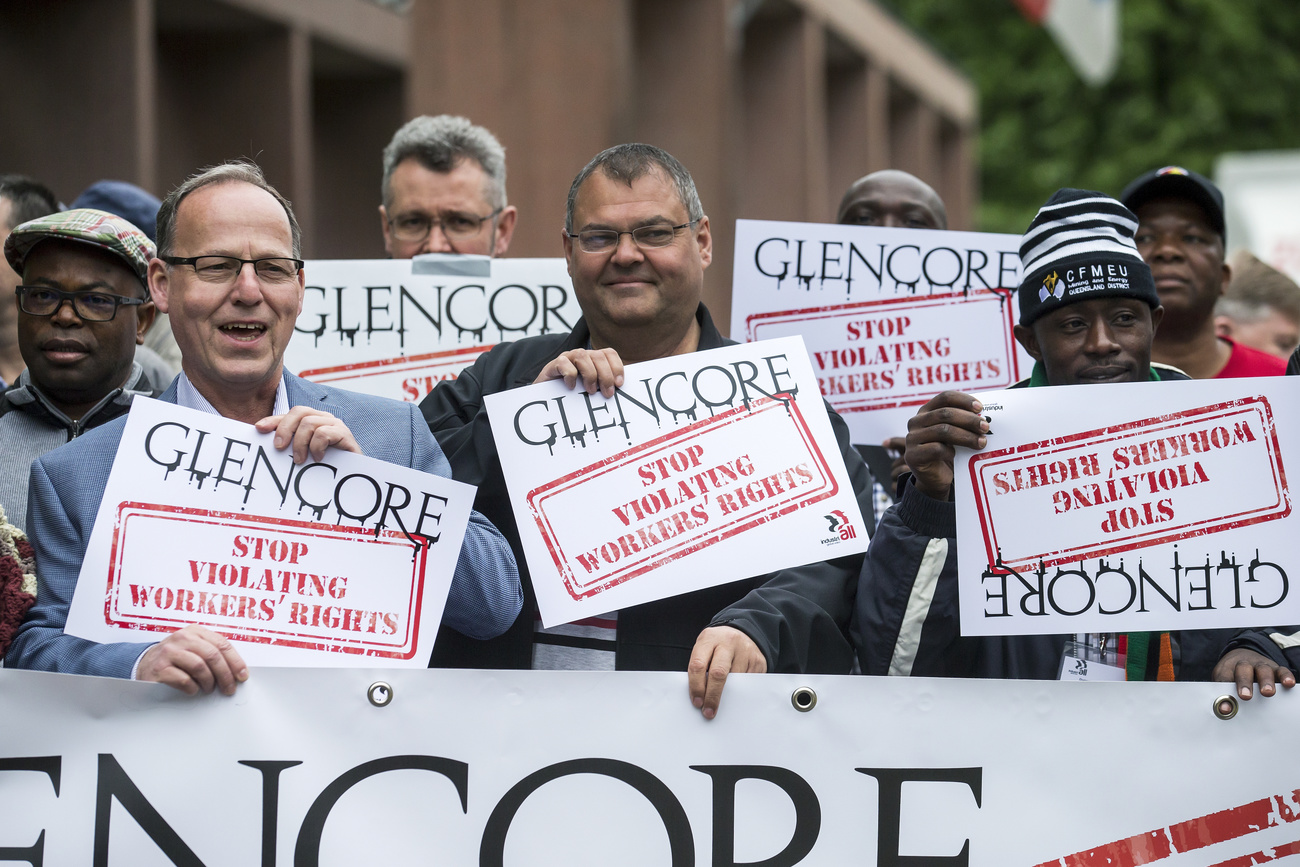

Cassis made a number of missteps, giving fuel to a growing chorus of critics. He made undiplomatic comments about the role of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in the Middle East conflict and tweeted public relations messages for the commodities company Glencore from a mine in Zambia. An economic liberal, Cassis also attempted to convert Swiss foreign policy to a form of foreign economic policy, much to the disapproval of the left.

“He has linked it more closely to economic needs and migration policy,” says Paul Widmer, a professor of diplomacy. His political opponents fear a “Switzerland first” policy. Fabian Molina, a Social Democrat foreign policy specialist, says of Cassis to SRF: “As a member of the government, he has prioritised business before human rights in foreign policy. I have some doubts that he can represent the whole population in role as Swiss president.”

“Foreign policy is domestic policy”

Foreign policy – alongside the pandemic – remains one of Switzerland’s major works-in-progress in 2022. Relations with the EU have never been so unresolved. From the beginning of his term he was at the helm of negotiations with Brussels.

In 2018, he took on a new chief negotiator, but still led the direct dialogue himself. He also chose to speak publicly on the issue, taking on the role of moderator. He listened to needs and mediated between the different interests of Switzerland and the EU. “Foreign policy is domestic policy,” he explained.

But there was no real movement on the outstanding issues between the two parties. In Switzerland, neither left nor right dared to make the next step. Brussels and Bern eyed each other with suspicion. Cassis used the time to set new priorities in development aid. The importance of Latin America was downgraded, and measures to reduce migration were given more weight in foreign aid. He set priorities in foreign policy: China and the Middle East. He also extended Switzerland’s diplomatic network.

But Cassis is measured today on the issue of Switzerland’s destiny in the EU, on which there was never much to be gained. So in his presidency year, he will be happy to turn to the more cheerful business of building his profile on the domestic scene. He hopes to “strengthen national unity,” he says. As a representative of a language minority – who also speaks the other national languages perfectly – he seems destined for this. “My goal is to enable differences of opinion to be experienced as an asset in this difficult situation. And not as a source of conflict,” he says.

An honorary position as an opportunity

Negotiations on international questions also remain on the agenda. Switzerland has almost secured a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council for the 2023-2024 period; a decision will be taken in June. And the Alpine country may organise a future conference on Ukraine. Cassis is still seeking dialogue with China on human rights and, in general, multilateralism remains at the top of the Swiss agenda: International Geneva, digital diplomacy, and the search for mandates for international mediations.

All of this also creates a positive image at home. And for Cassis, it offers the potential to score a few important points to improve his image in parliament and the population.

More

Switzerland’s 20 living ex-presidents: a world record

Adapted from German by Catherine Hickley

Translated from German by Catherine Hickley

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.