Quantum technology enjoys first commercial successes

Quantum physics is moving out of the lab and into the marketplace. Switzerland, a strong researcher in this field, doesn’t want to miss out and is launching its own quantum initiative. For now, though, it will have to make do without Europe.

The United States, China and the European Union are investing hundreds of millions in products that make use of the very special properties of the infinitely small. Switzerland is not lagging behind. Over the past 20 years the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), universities and the private sector have committed nearly CHF330 million ($360 million) to three National Centres of Competence in Research, the last of which opened its doors in 2020.

So what are the results? According to the SNSF, Swiss researchers have contributed to “the demonstration of the superfluid nature of polariton condensates”, have advanced the technology of “quantum cascade lasers” and are working to “develop reliable, fast, compact and scalable spin qubits in silicon”.

If you didn’t catch all of that, you’re not alone. Quantum physics continues to be a closed world for ordinary citizens. Even professors who have devoted their careers to it admit that no one approaches this field without a fair degree of suffering, for the world of particles and atoms can only be understood through equations, which defy the common sense even of mathematicians. There’s no way to form a mental picture of it; the mind just boggles. Nor can it be explained by diagrams; even 3D visualisation does not help. (Though this article might).

More

Quantum physics: the ‘laws of the absurd’, explained

Yet quantum physics is anything but an abstract construct. It is nature that is bizarre, not the theory describing it – a theory that 120 years of experience has done nothing to undermine.

Now available in shops

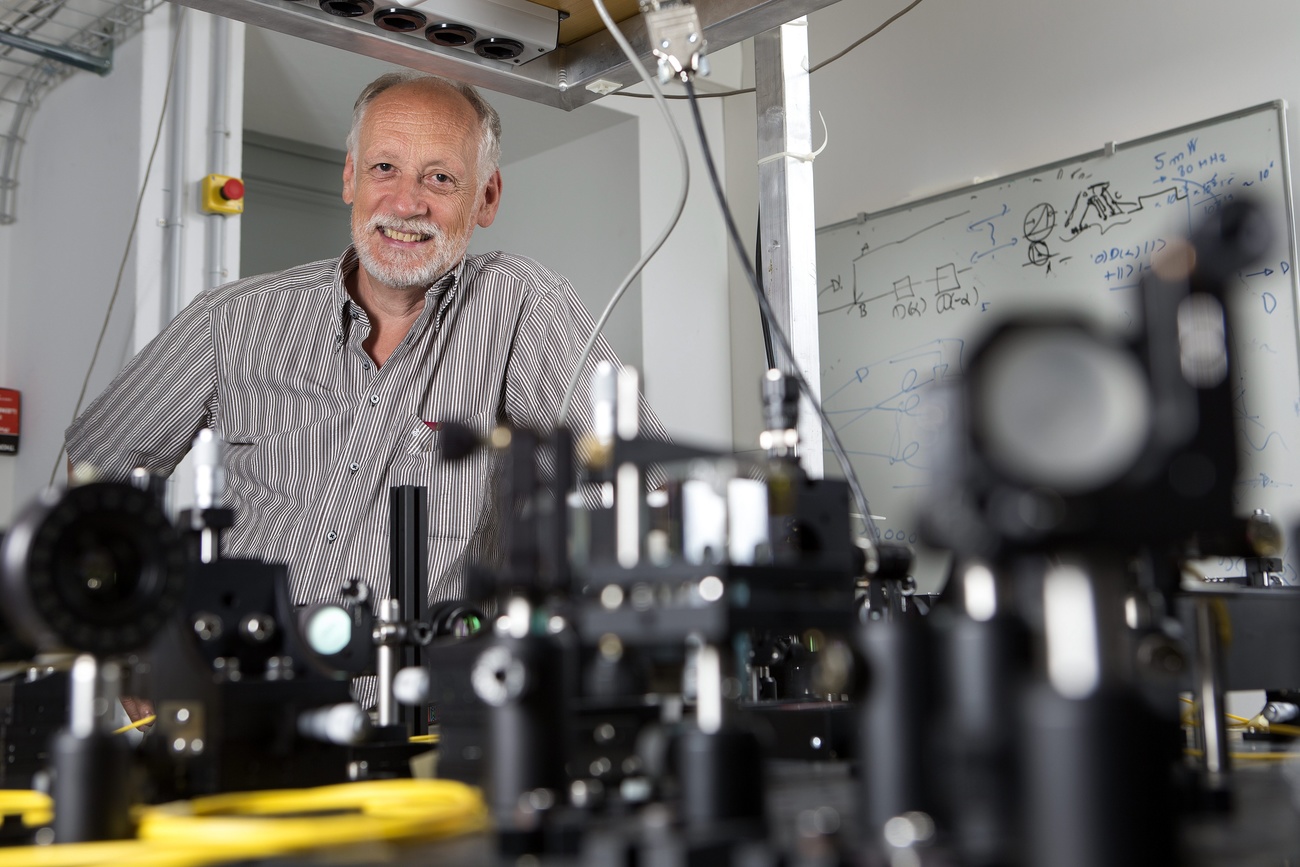

Having emerged from the laboratories, quantum technology is enjoying its first commercial successes. In Geneva, the work done by physicist Nicolas Gisin and his group in the field of quantum cryptography gave birth to a pioneering product that has become a world leader in its field. For 20 years ID QuantiqueExternal link has been marketing reputedly unbreakable encryption systems, now to be joined by random number generators (as already found on some Samsung phones) and quantum sensors, capable of measuring light to the nearest pixel or photon.

Also Swiss made, the quantum sensors manufactured by QnamiExternal link in Basel are up to 100 times more accurate than conventional sensors. They are used to characterise materials or detect defects in computer chip elements, but they are also a valuable tool for research in medicine, biology and chemistry.

Another company that has emerged from Swiss quantum research is Alpes LasersExternal link with its quantum cascade lasers, mentioned above. This type of infrared laser is already widely used in research, industry and medicine. It displays unrivalled precision in detecting and analysing gases and other chemicals.

Determined to stay in the race

Quantum technology has become very trendy. According to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), the sector attracted more than $2 billionExternal link (CHF1.85 billion) in private funding in 2020 and 2021, double that invested over the previous decade.

On top of this comes government support, particularly substantial in the case of China – which will not disclose how much it spends in these fields. As for the future markets for these products, BCG estimates them at $450 billion-$850 billion over the next 15-30 years.

It is only logical that Switzerland should launch its own Quantum InitiativeExternal link. The aim is to “secure the country’s prominent position […] and enhance international networking”. The total amount that the government is allocating to the project – CHF10 million over two years – nevertheless seems quite modest. Gisin, who is also the president of the new Swiss Quantum Commission, agrees.

“The aim is to multiply this figure by four, to reach CHF20 million a year,” he says. And what is this money for? Not only to develop the fields where Switzerland is already strong, but also to educate and train not just academics (who are already doing well, according to Gisin) but also engineers and apprentices.

The funds will further be used to provide selective, rather than blanket, support to start-ups, and to develop certain infrastructure facilities at the national level, for example in quantum cryptography, as is currently being done throughout Europe.

The quest for the grail

Then there is the famous quantum computer. Here, Gisin tries to tone down the rhetoric. “I would rather speak of a quantum processor, a machine that stays in a laboratory and can be consulted remotely, via the internet.” He believes Switzerland should also get cracking on this, “and not just say that it will leave it to the Americans, the Europeans or the Chinese”.

But what will this much-awaited phenomenal computing power be used for?

In 2019 Google claimed to have achieved “quantum supremacy” with its Sycamore processor. It reportedly accomplished in 200 seconds an operation that would take a conventional supercomputer 10,000 years. This figure was immediately challenged by IBM, which spoke of two-and-a-half days. But beyond this marketing squabble between competitors, the fact remains that Google’s machine performed a calculation that was tailor-made for it and was full of randomly generated numbers – a calculation which has no practical use other than demonstrating Google’s technological superiority.

Gisin acknowledges that some quantum feats are overhyped – “especially promises of a universal computer in the next five to ten years”. He nevertheless considers it an “extremely impressive” achievement to have demonstrated that at least one problem can be solved more efficiently using quantum rather than conventional technology.

Dreaming ahead

And there will be more such exploits. Ultimately, quantum processors could be very useful in developing new molecules – not in creating them, which will remain the preserve of chemists, but in designing them and simulating their behaviour and properties before they are actually produced.

The fields of application for this are immense: from medicines to solar cells via the whole range of new materials, whatever their use.

Does this include potentially malicious uses? Gisin is aware of this threat. “I cannot promise that quantum computing will do only good. It’s like all technologies. Quantum cryptography can be used, for instance, to protect hospitals from computer attacks. But we could also imagine terrorists using quantum cryptography in order to remain hidden.”

As for those who dream of using quantum computers to improve prediction models in financeExternal link, Gisin replies with a shrug: “The stock market can also be seen as a random number generator.”

Going it alone

One thorny question remains. After voters accepted the right-wing initiative against mass immigration and after the Swiss government walked away from talks on a framework agreement with Brussels, Switzerland was excluded from the Horizon Europe programme. This defines and funds research and innovation in the EU, with a budget of more than €95 billion (CHF94 billion) until 2027.

It’s not just about money, though, but also about networks, exchanges and cooperation, not to mention markets for Swiss companies already selling quantum products.

The situation is, as Gisin puts it, “dramatic”. “We don’t come up with new ideas sitting by ourselves in our offices. We have to talk to other people, bounce ideas off them, challenge each other. And our natural partners are above all the Europeans.”

His Zurich-based colleague Klaus Ensslin, who headed the National Centre of Competence in Research “Quantum Science and Technology” for 12 years, sees this as a “painful situation, a clear case of science being held hostage to politics”. As he told the press office of the federal technology institute ETH ZurichExternal link in December 2022, “quantum research is a jewel in Switzerland’s crown, but it’s all been sacrificed. And the consequences for young researchers will be really tough”.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss. Translated from French by Julia Bassam.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.