Swiss researcher finds new ways to discover dialects

The Dialäkt ÄppExternal link was just supposed to be entertaining, with a quiz that predicted users’ Swiss hometown based on dialect. But when the data started piling up, linguist Adrian Leemann knew he was on to something big. Now, the Swiss researcher is taking his dialect studies back in time to understand how languages change.

Usually, linguistic researchers might have data to analyse from twenty or thirty speakers, says Leemann, associate researcher at the University of Bern. After the Dialäkt app’s release in 2013, some 100,000 people participated.

“That was a bit of an ‘Aha!’ moment where you realise this has huge potential,” says Leemann, who at the time was a linguist and phonetician at the University of Zurich.

Leemann, who was born in the northwestern Swiss city of Aarau and received his PhD in linguistics from the University of Bern, has always been interested in language variations. His mind latches onto changes in speaking rates, the melody of speech, and differences in vowel pronunciation. He is so distracted by sounds that he wears ear plugs and headphones to create absolute silence while he works during his train commute from Zurich to Bern.

But it’s the enthusiasm for exploring new ideas that propels him. After the success of the Dialäkt Äpp, he eventually took positions at the University of Lancaster and Cambridge University, where he worked on a similar app to detect English dialects.

Now, the 39-year-old Leemann is back in Switzerland having been awarded the Eccellenza Professorial FellowshipExternal link from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). The CHF1.6 million ($1.6 million) award will allow him to lead his own team of researchers to conduct a survey of Swiss German dialects for comparison with the Sprachatlas der Deutschen SchweizExternal link, a database – or historical atlas – of dialects from the 1950s. His project, which begins in September, will build on his findings in the Dialäkt App.

More homogeneous dialects?

Part of the research will address the question of change. Inés de la Cuadra, deputy head of the careers division at the SNSF, says there is evidence of dialects becoming homogenised throughout Europe. “Is this also true for Switzerland?” she wonders.

The Dialäkt Äpp seemed to illustrate this phenomenon.

“You see pretty clear trends of what we call levelling,” Leemann says, “meaning that linguistic diversity seems to be disappearing to some degree, especially in terms of dialect words.”

Take, for instance, the apple core.

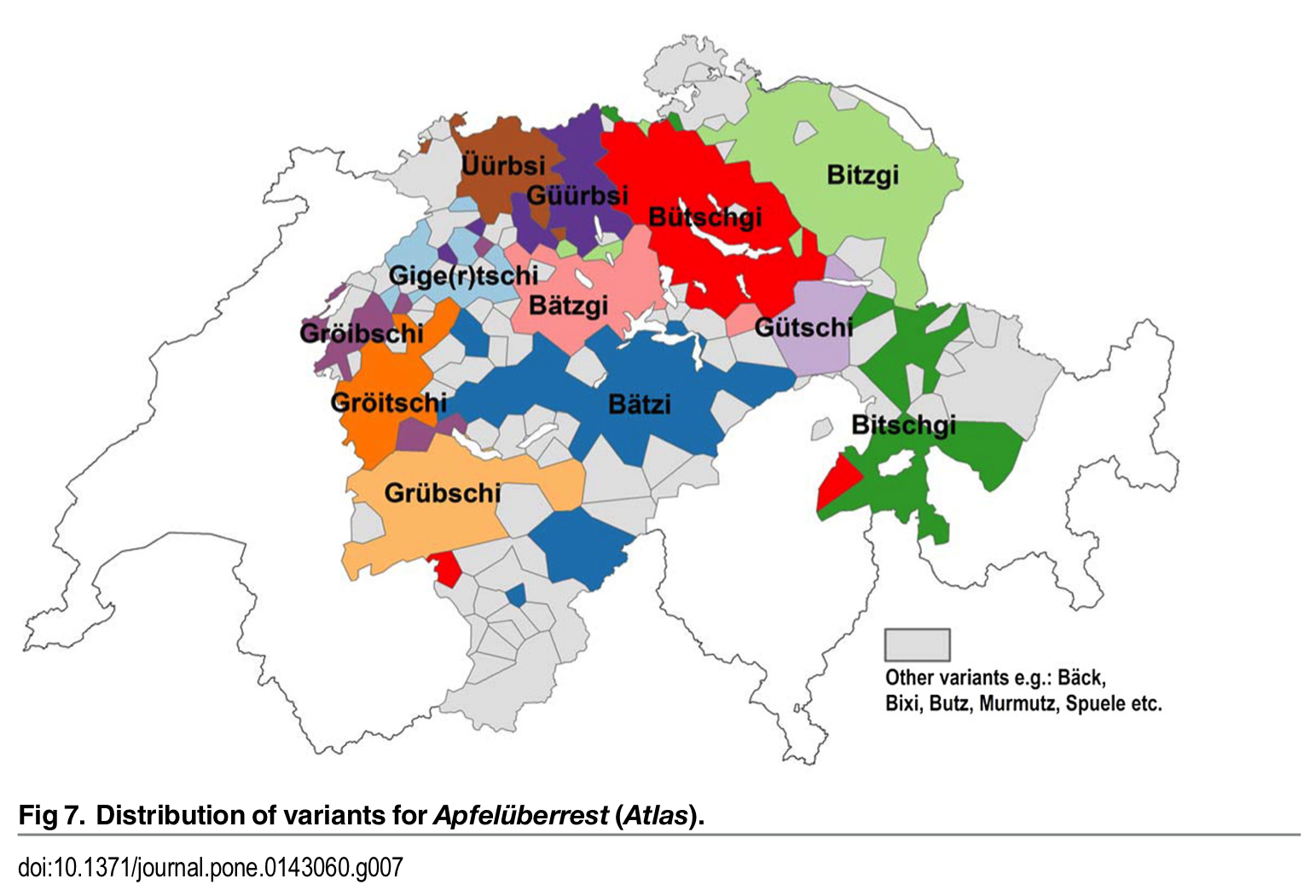

In the Dialäkt Äpp, users could listen to 39 variations of the German word for apple core, “Apfelüberrest”. Two of those variables are “Bäck”, used mostly in the canton of Schwyz in the 1950s, and “Bütschgi”, which was used predominantly in the canton of Zurich.

Historical map of terms for “apple core”

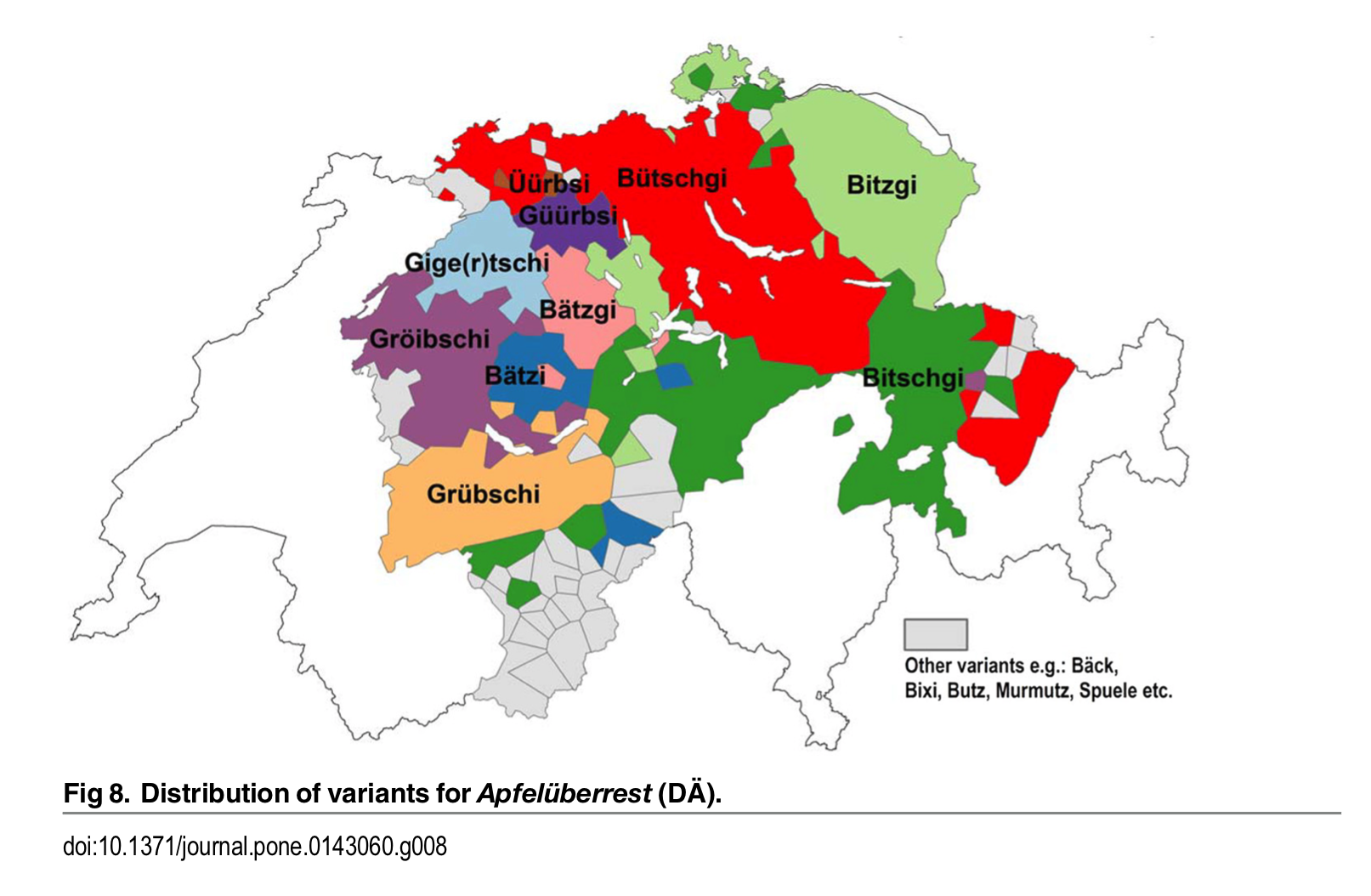

“When you look at today’s map you see how the term Bütschgi spreads towards central [and eastern] Switzerland,” Leemann says. He expects the dialect map will look significantly different in 100 years’ time.

Current map of terms for “apple core”

Mobility appears to play a big role in levelling.

Leemann gives the example of someone who commutes to Zurich from central Switzerland. Over lunch with colleagues, the word for “apple core” might come up, and the commuter may adapt the central Swiss Bäck to the Zurich term Bütschgi so everyone understands.

It’s a phenomenon known as short-term accommodation. If this happens several times, a person might begin to use the new word automatically at home, where family members accommodate them, leading to longer-term change.

dialect for apple core

dialect for apple core

A new approach to dialect research

Leemann will face several challenges in conducting his historical dialect research. First, he will have only five years to complete the research compared with the nearly 20 years of data collection and recordings in the historical atlas, dating from 1939 to the late 1950s.

Of the 2,500 linguistic variables identified in the atlas, Leemann will look at about 300. For example, a variable could be the beginning vowel sound of the Gcerman word for evening, Abend, which in dialect is pronounced either Aabe or Oabe, among other variables. For now, he plans to record one man and one woman from each of 550 Swiss villages or towns. Automatic transcription will speed up the process and computer interfaces will be able to link word choice to regional maps.

Participants will also be younger than in earlier such studies. Previously, researchers worried that old dialects were dying out, so the historical atlas documented speech from older, rural people, mostly men, to capture dialects from around the turn of the century, Leemann says.

His new approach intrigued the Swiss National Science Foundation. The organisation’s de la Cuadra says the experts weighing his research proposal appreciated the new research strategy of questioning both male and female participants who commute about 12 kilometres per day, rather than focusing on older men who work in agriculture.

Applying the findings

But why invest CHF1.6 million to determine who says Bütschgi instead of Bäck?

The data can be used for myriad purposes, from helping voice recognition technologies understand dialects to identifying a caller making a threat. That’s what happened when a phonetician studied an audio recording of a man claiming to be England’s Yorkshire RipperExternal link. The phonetician was able to study variations in the caller’s speech and narrow down his location to within “walking distance”.

Dialect can even be a hot topic in pop culture. When commentators said the Duchess of Sussex Meghan Markle’s American English was adapting to British English, Leemann joined his colleagues in making technical comparisons – and didn’t find any evidence to support itExternal link.

And there’s no shortage of interest from the public, as evidenced by the tens of thousands of app participants.

Leemann says people find dialect apps intriguing because it tells them something about their identity, “like a badge on their chest”.

“Especially in German-speaking Switzerland, it’s a big part of people’s identity, their local roots and heritage,” he says.

Which Swiss dialects are most attractive?

Leemann performed a studyExternal link with sentences recorded by the same speaker in standard German as well as dialects from Bern and Zurich. He then played the recordings for people from Bern, Zurich and Lucerne and asked them who they would prefer to have perform their surgery, hire as an assistant, or go on vacation with. Participants in all three locations preferred the Zurich German speaker for each scenario, although Bernese German came close on the question regarding with whom they’d rather go on holiday.

Leemann says that in the study, Zurich German, while not having the most positive associations stereotypically, was perceived as most competent. Bernese German, stereotypically the most-liked dialect in German-speaking Switzerland, is not evaluated as particularly competent when actually being listened to.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.