A plan to save Swiss ski resorts from sprawl

Fiona Pià has a radical idea for helping Swiss ski resorts limit sprawl and congestion, while simultaneously accommodating more visitors and protecting the natural landscape. To explain, she took swissinfo.ch on a tour of one of Switzerland’s biggest attractions.

Like many Swiss ski resorts, Verbier has grown in an organic, piecemeal fashion since it began operating in the 1950s, without a unified vision for urban design and transportation. The views are breathtaking and town itself is festively decked out, even on a grey day in late November. But although ski season isn’t yet in full swing, the traffic is dense and makes walking and talking difficult.

“Verbier’s size is about five square kilometres [about two square miles], so to do it all by walking takes too long – it is a town that has been planned for cars,” says PiàExternal link, a Swiss federal institute of technology Lausanne (EPFL) researcher.

Buses use the same roads as the cars and there’s no efficient alternative to driving. She says people are fed up with the noise and mobility problems.

“Verbier did not have much planning. It was developed by reproducing individual chalets, because that’s the image people like and associate with the mountains. You can do that when you have a little village, but when you have a town of 30,000 people and you simply reproduce this model, then you get the urban sprawl that you see here,” says Pià, as she gestures to the line of cars winding through one of Verbier’s main thoroughfares.

As more and more individual vacation homes have been built over the years – according to the traditional model of the isolated chalet – many Swiss ski resorts have become sprawling agglomerations connected by overcrowded roads, which consume the very landscape that holidaymakers come from around the world to enjoy.

This is a problem in Verbier, which was the focus of Pià’s doctoral thesis research.

More

The problem with the Swiss chalet

Inhabited infrastructures

Pià’s argument is simple: Verbier needs to abandon the single chalet model. In its place, she proposes “inhabited infrastructures” in the future, which would combine housing and public services with mobility and transportation options.

Such a model, she says, would not only mitigate problems associated with sprawl and congestion, but also preserve the natural environment and secure the resort’s economic future.

“Today, we have arrived at a point where we have to think of a new model of transportation and densification. It is dangerous to continue with the chalet model, because we will eat up all the territory if we continue this way,” she says.

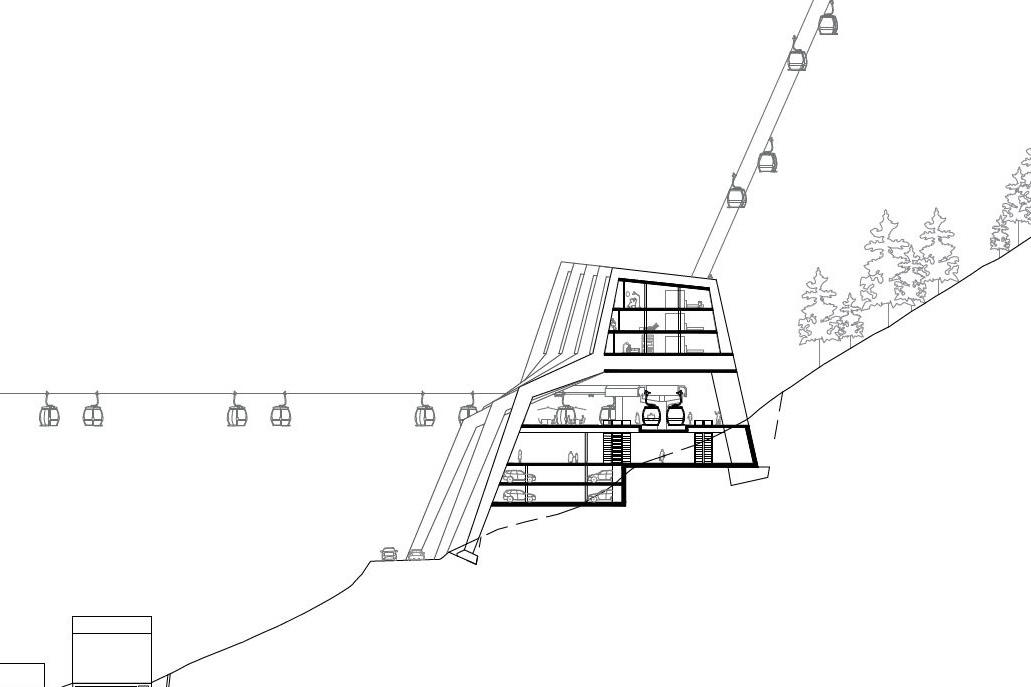

So how would it work? In Verbier, Pià envisions five “expanded” cable car stations located in different corners of the resort but all connected.

These 500 metre-long buildings would combine lodging and apartments with pedestrian areas, public transportation, shopping, food, and of course direct access to the cable cars themselves. A visitor to Verbier could walk from a cable car drop-off to their hotel, attend a concert or restaurant, or even take a stroll along a pedestrian path, all without leaving the inhabited infrastructure. Longer distances – to a ski slope, to the centre of the village, or to the nearby village of Le Châble – could all be accomplished via cable car.

“In winter, one of the things that creates traffic is when people want to go to the cable car to ski. With my system, you can ski directly to the cable car departure point, without taking a private car,” Pià says.

According to Pià’s model, the inhabited infrastructures could be built using the 10% of constructible public surface area that still remains in Verbier, while using up to six times less soil than individual chalets.

A “remarkable paradox”

The Swiss have been aware for some time of the problem of urban sprawl. But Pià argues that the government’s solution – a 2012 law that limits the construction of second homes to no more than 20% per commune – is actually counterproductive.

Pià explains that, in a “remarkable paradox”, the so-called ‘Lex Weber’ initiativeExternal link demonised urbanisation as the cause of sprawl, when in fact, the problems faced by communities like Verbier are caused by the fact that they are too low-density.

“It is just this model that leads to urban sprawl and encourages people to use their cars,” Pià said in an earlier EPFL statement.

Pià says that building inhabited infrastructures would not require any change to the Weber legislation. And although she developed her model to specifically address the challenges faced by Verbier, she says it could also be adapted to other ski resorts across Switzerland.

A “utopic” vision?

But efficiency and mobility arguments aside – does Pià think people can be convinced to give up the beloved chalet model in favour of inhabited infrastructures?

“I think people like chalets not just because they’re an archetype, but because of what they represent: to have contact with nature and a view of the mountains, and to have your own cocoon,” she says. “You will have those things with the inhabited infrastructure. It’s a new way to live in the mountains that will really protect nature.”

Pià will be formally presenting her plan to the Verbier community in January 2017. But André Guinnard, the founder of a Verbier property agency External linkwhich last year celebrated its 50th anniversary, foresees some resistance to the idea.

“It is very difficult to densify more now. We have to convince local people who vote, and you need a budget, you need the rights, you need to change the regulations. That’s not easy – it will take 15 years, minimum. That’s why I say it’s utopic today,” he says.

Eloi Rossier, president of the municipality of Bagnes, to which Verbier belongs, echoes Guinnard’s concerns. In November he told the Tribune de Genève newspaper that Pià’s project could help Bagnes authorities to “broaden [their] thinking”, but that the municipality had its own priorities to contend with, such as renovating existing buildings and creating more parking areas.

“Verbier developed in the aftermath of the Second World War, and this was done with the car. It is difficult to tell people today to give it up,” Rossier told the newspaper. “When we make a decision, such as changing a stretch of motorway, we face an avalanche of opposition.”

Tough times

Despite problems with overcrowding and congestion, many Swiss ski resorts are at the same time desperate to attract more guests. According to the Swiss cable car umbrella organisation, Seilbahnen Schweiz, ski resort visits during the 2014-2015 winter season were nearly 20% below where they were a decade before.

Seilbahnen Schweiz put the decline down to a particularly mild and sunny winter, which made for poor snow cover – something that Swiss ski resorts will increasingly have to adapt to as the climate warms.

Another factor was the “Frankenshock” of January 2015, which saw the abrupt uncoupling of the Swiss franc-euro exchange rate, resulting in a “strong franc” that set the price of a Swiss ski vacation too high for many foreign visitors. According to Seilbahnen Schweiz, during the 2014-2015 winter season, the average price of a one-day adult daily ski pass across 39 Swiss resorts was CHF58 ($57).

Verbier in brief

Today, Verbier has about 2,160 chalets, which amounts to about 1,350,000 square metres of construction. As of 2013, Verbier had about 3,000 permanent residents, accounting for about 40% of the total population of the Bagnes municipality. Just over half of permanent residents are Swiss, with 45% coming from other countries. Verbier can accommodate upwards of 30,000 people during peak tourist season.

When you go on vacation, are public transport options and proximity to nature important to you, or are there other aspects you value more? Share your thoughts in the comments!

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.