Saving microbial diversity, one stool sample at a time

Billions of viruses, bacteria and other micro-organisms live in our intestines, quietly carrying out indispensable functions for our well-being. But microbial diversity is under threat, which is why a new project to create a global collection of human and animal microbiome has been launched in Switzerland.

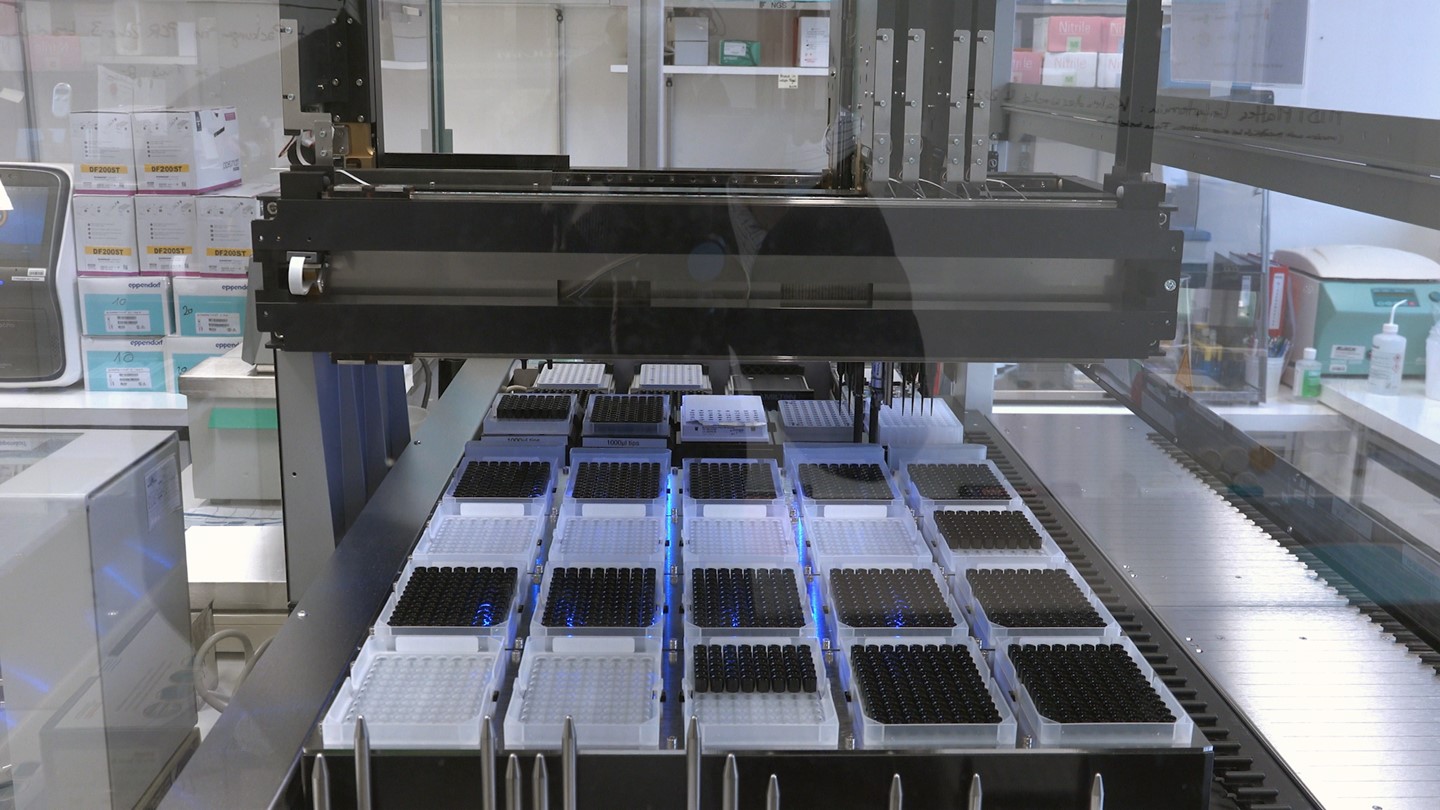

The sequence robot housed in a laboratory at the University Hospital Basel has a lot of work to do. It is busy analysing the genetic information of bacteria in dozens of faecal samples that were delivered to the lab in small tubes. The samples were taken from tourists just back from India.

“We get samples from all over the world,” says Adrian Egli, the physician who heads the Clinical Bacteriology and Mycology Unit at the University Hospital Basel. Egli is currently conducting the first trials for an international project dubbed the Microbiota Vault.External link

Our intestinal flora significantly affects our well-being, both mental and physical, and can help doctors shed light on a person’s health. But microbial diversity is being threatened by urbanisation and environmental changes. This is why researchers with the Microbiota Vault are trying to create an archive of samples, collections and research from around the world on the microbiome – the full range of micro-organisms – of humans and animals.

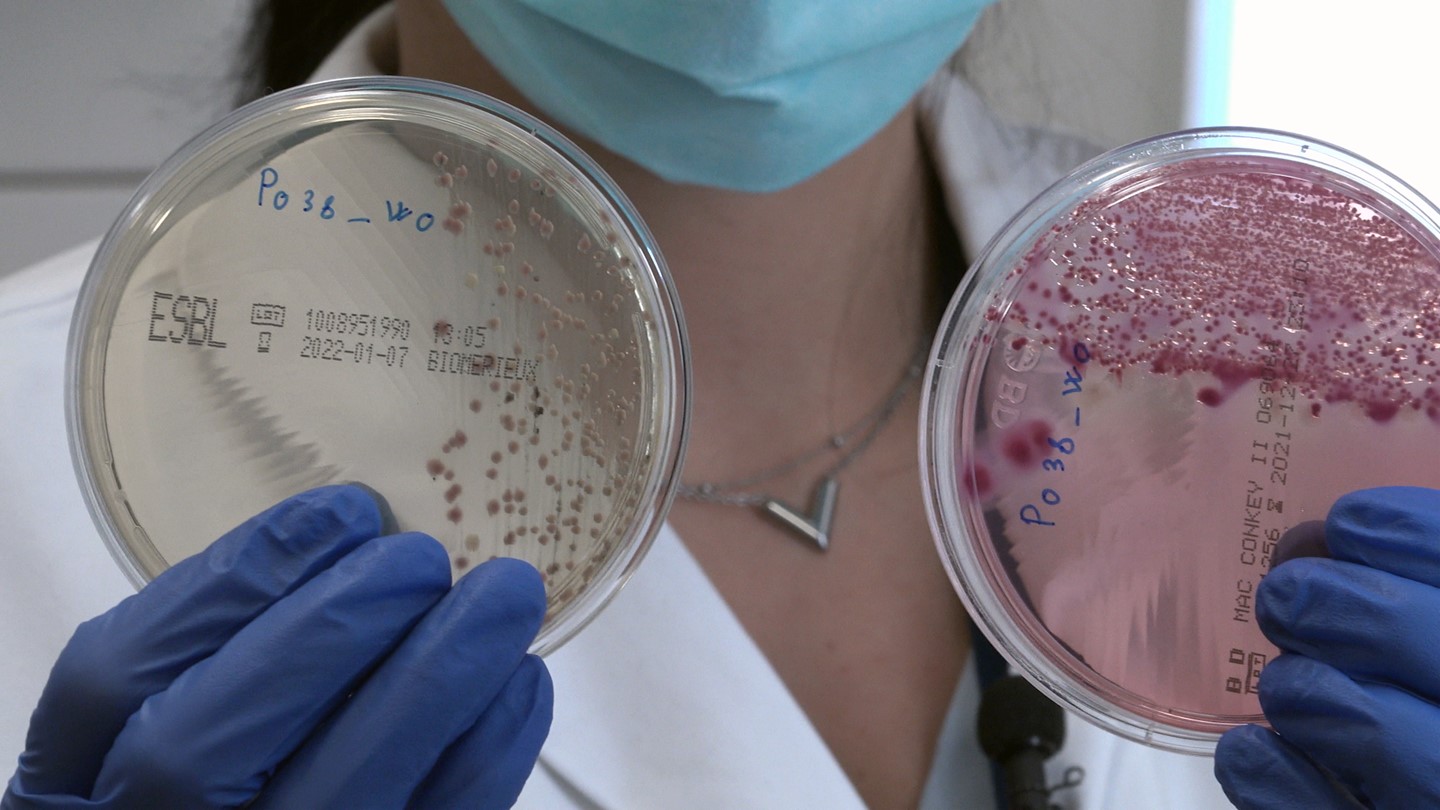

Egli hopes that the samples from India will help researchers to understand how the composition of bacteria changes in our intestines and how it is connected to anti-microbial resistance. For example, after a trip abroad, it is possible that our intestines are teeming with bacteria that pose a threat to our health because they are multi-resistant to antibiotics.

The body of an adult houses hundreds of bacterial species that can weigh up to 2kg in total and have the ability to significantly influence our metabolism. The Microbiota Vault aims to help scientists better understand these complicated interactions.

A single stool sample contains billions of micro-organisms but only a few grammes are sufficient for sequencing.

“We divide the stool samples into small portions and freeze them,” says Egli. This way researchers can establish the best storage options for the different samples.

Maintaining diversity

Intestinal health is having a moment in the spotlight, helped by bestselling books like German physician Giulia Enders’ Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body’s Most Underrated Organ, first published in 2014. The billions of micro-organisms living in our intestines are not only crucial for our digestion, but they carry out many additional functions, like helping in the absorption of vitamins or stimulating our immune system.

Our body processes food through several chemical reactions. Only some of these reactions occur directly in our bodies, and microbes do most of the work. A diverse microbiome makes for healthy humans and animals.

In addition to human and animal micro-organisms, the Microbiota Vault is also collecting microbes found in fermented foods that could give scientists some other insights. Lactic acid bacteria in particular are believed to be beneficial to the human body.

“Across the globe there are threats to microbial diversity,” says Dominik Steiger, who is coordinating the launch of the Microbiota Vault initiative. Urbanisation, globalisation and rapidly changing living conditions in indigenous societies as well as the change in ecosystems due to climate change and the destruction of natural habitats are all to blame.

“We are losing this diversity at a time when we are just beginning to understand the significance of the microbiome,” Steiger adds.

Steiger believes it’s important to build an exchange system between poor and rich countries that is “based on equity and mutual benefit”. The implication here is that Swiss researchers should not only collect, sequence and catalogue samples – they should also work with international experts and set up a network of existing collections.

“We guarantee that all local samples that have been stored with us will remain the property of the researchers who collected them,” says Steiger. “It’s based on trust.”

Switzerland chosen as location

The initial idea for the project came from a group of international microbiome scientists who published an article on preserving microbial diversity in the journal ScienceExternal link in 2018. They launched a feasibility study to find the best place for a Microbiota Vault – an initiative not unlike the Svalbard Global Seed Vault External linklocated in the Artic that houses the world’s largest collection of crop diversity. The study concluded that Switzerland was the best location for the microbiome project.

Steiger stresses that the choice of location does not make it an exclusively Swiss affair. The Vault was launched at the end of 2021 as a collaboration between the University of Basel, the University of Lausanne, the federal technology institute ETH Zurich and Rutgers University in the United States.

The team raised CHF1 million ($1.09 million) from foundations around the world, among them two Nobel Prize winners.

“A project like this usually runs over decades, which makes it particularly important to base it in a stable and neutral country,” says Egli. Sufficient funds and the right kind of facilities to map the samples correctly also play a major role.

“This project is an incredible opportunity for Switzerland.”

Inside the lab

Back at the University Hospital Basel, a researcher is placing samples inside a giant freezer that keeps a constant temperature of -80°C. A thick layer of ice inside the freezer is a reminder of the necessity to work quickly and carefully to avoid damaging one’s skin.

“You can’t just put bacteria in the freezer like that because they will die,” says Egli. Crystallisation destroys bacterial cells. For the Microbiota Vault, special preservatives will be added to the bacteria to help them survive the freezing process. The procedure is being worked out in the pilot phase of the project.

Asked if there is any danger that the bacteria will become contaminated or modified over a long storage period, Egli explains that scientists will document the samples using internationally recognised and standardised methods. Information on whether a sample contains antimicrobial resistance or toxins will be clearly indicated. Hazardous pathogens will be frozen separately.

Quality control of the Microbiota Vault will involve testing the stored samples to note any changes that might happen during the freezing process. The team will carefully document the bacterial diversity of a sample before freezing to make sure that nothing has changed once the freezing process is over.

Clear documentation is a central aspect of the project. “We must use the same terminology worldwide,” says Egli. “It is like speaking a language – you can’t just write something in French and then write something else in German.”

For the long-term storage of the more than 100,000 samples, the scientists envisage using one of the old military bunkers in the Alps.

“But it still requires a huge amount of investment, and it will take a few more years before we are ready,” says Egli.

Recognition for intestinal bacteria research

This month three researchers from the University of Bern and the University Hospital Bern — Stephanie Ganal-Vonarburg, Hai Li and Julien Limenitakis – were awarded the Pfizer Prize for showing how our gut microbes influence the formation of antibodies.

The Pfizer Prize is one of the most important research prizes for medicine in Switzerland. It is awarded annually to young scientists who have made pioneering contributions to research in five areas. Each winner receives CHF15,000.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.