Why Switzerland is struggling to ditch fast fashion

The Swiss spend the second most globally on “fast fashion” – clothes that are quickly used and thrown away, contributing to the climate crisis. But the few researchers trying to find better options must fight to get funding and recognition for their work.

“We are bad; we are really bad,” says Katia Vladimirova over a cup of coffee, which is cold by now. She’s been speaking at length about herself and other women who can afford fashionExternal link but buy an excessive amount of cheap, short-lived items.

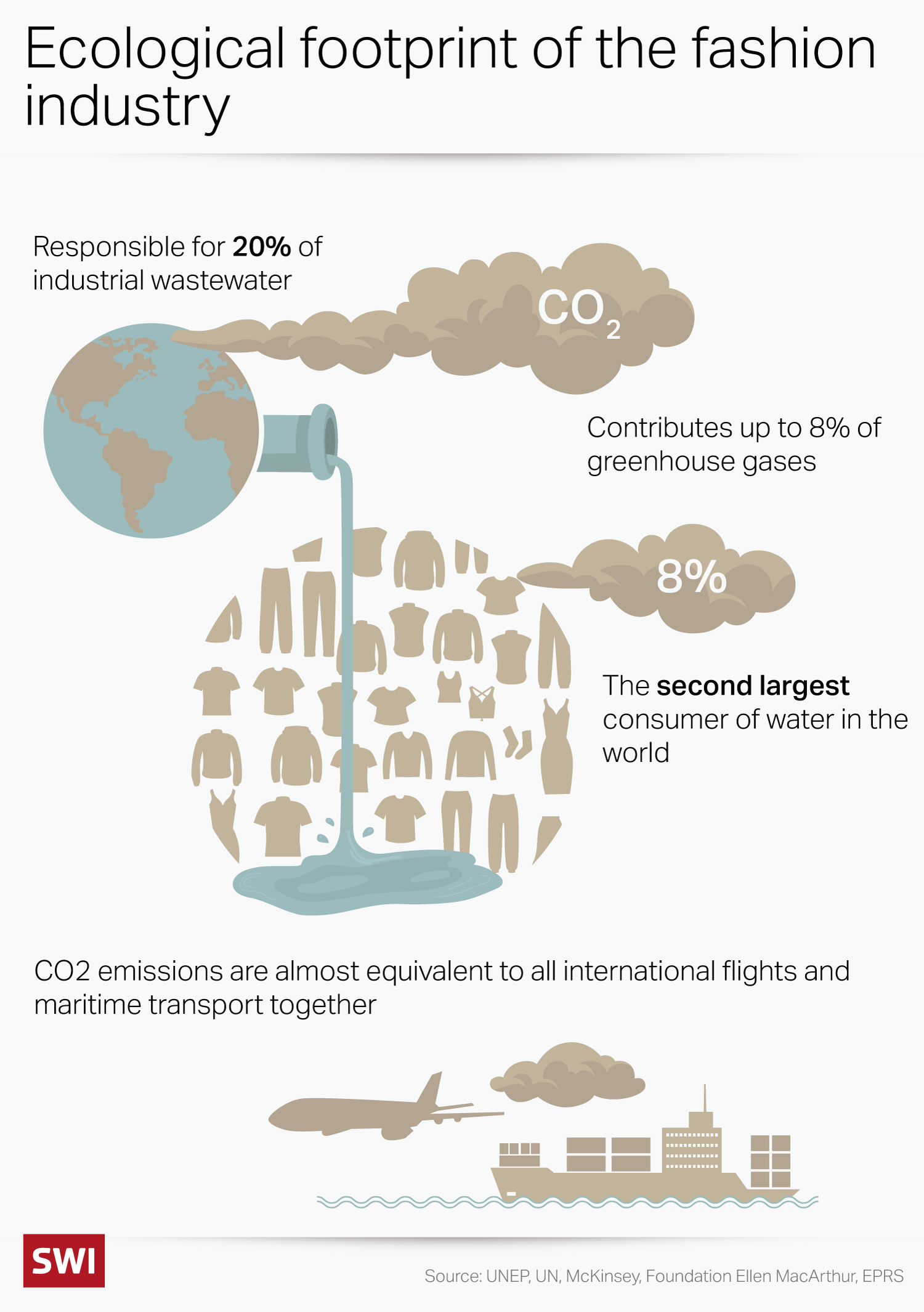

The fashion industry generates up to 8%External link of global carbon emissions, about the same as emissions from shipping and international flights combined. Before opening her eyes to the disastrous impact of fashion on the environment and people, Vladimirova used to go on shopping sprees and was often first in line when there was a sale. Today, the 36-year-old buys second-hand items and is a researcher in sustainability, consumption and fashion at the University of Geneva.

Vladimirova, originally from Russia, studied and worked in the major fashion capitals of London, New York and Milan. When she moved to Geneva in 2018, she was disappointed to discover that one of the richest cities in the world did not offer much besides luxury stores and fast-fashion chains. As part of her research, she started mapping out consumer trends in Geneva. In particular, she looked for local vendors that aim to reuse materials and reduce waste. “I thought I would find more diversity, but there is still a strong presence of disposable fashion,” says Vladimirova. Her report, funded by the city of Geneva, was published at the end of April.

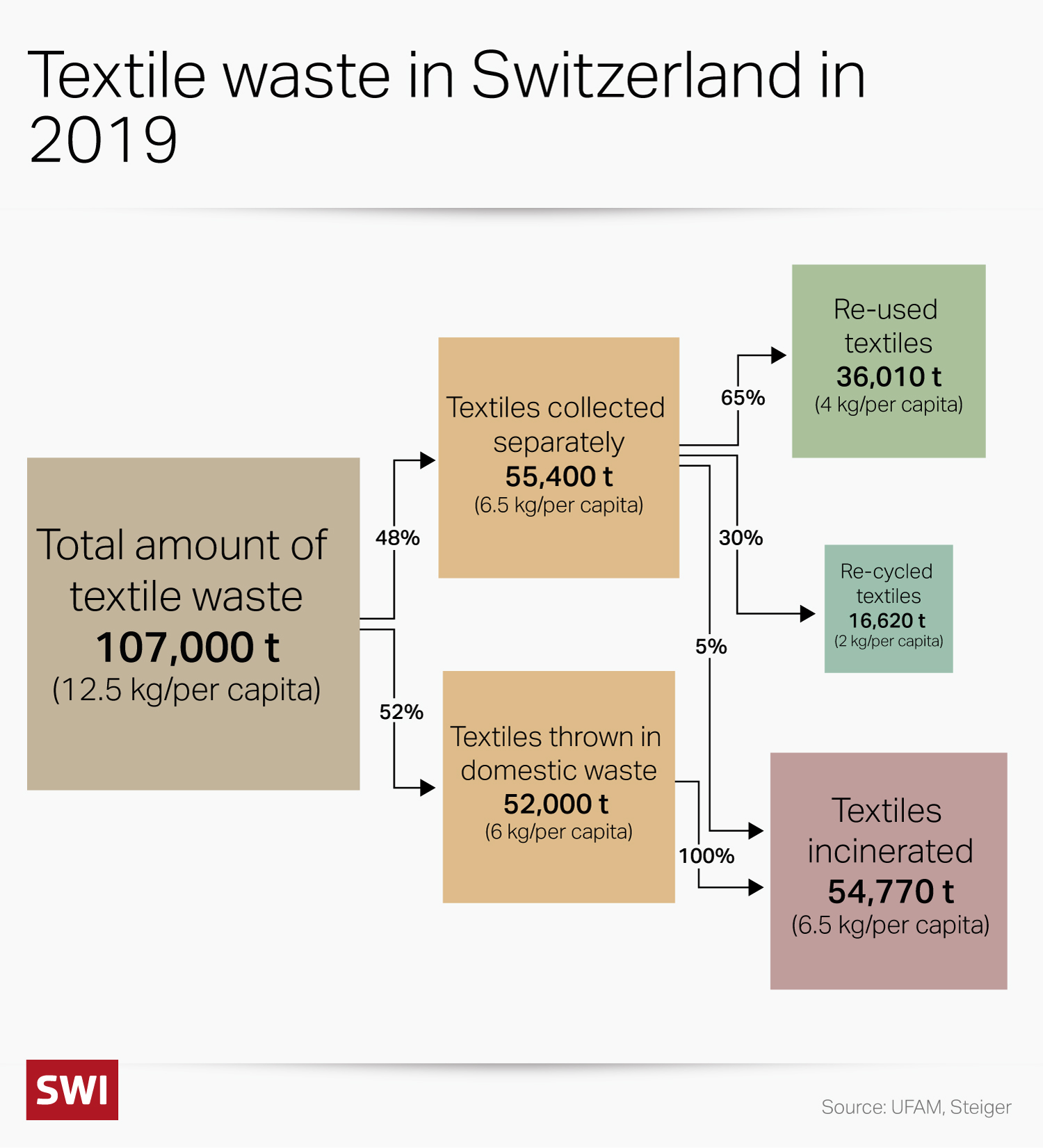

Data indicates that this is not only true in Geneva: after Luxembourg, Switzerland as a whole is second only to Luxembourg when it comes to per-capita spending on clothing and shoes, of which only around 6% are sustainably produced. Swiss consumers discard over 100,000 tonnes of clothes every year, only half of whichExternal link is donated, resold or recycled. The other half is incinerated to reduce the amount of textile waste piling up in landfills (see graphic below). In most cases, these are practically new clothes, sometimes even with the label still on. The practice feeds into clothing manufacturers’ bottom lines since mass-produced clothes and shoes that are thrown away are replaced after a short time.

Slow progress in Switzerland

Although numerous initiatives have emerged worldwide in recent years to raise awareness of sustainable and responsible fashion consumption, Switzerland still lags behind other European countries. There is hardly any research in this field coming out of the Alpine country, and the few local researchers find it difficult to get their studies off the ground.

Katia Vladimirova is one of them. “Working on clothes is not very popular in the research environment,” she says. In her career, she has constantly been confronted with a certain disregard for fashion research. In Switzerland, obtaining public funds proved particularly difficult. To secure grants, researchers must put in a lot of time and energy. The initiative to produce a report on Geneva’s textile ecosystem did not come from the city but from Vladimirova, who managed to convince city officials that her idea was worth pursuing. Finally, in 2020, the municipality decided to support the project with CHF50,000 ($56,000) over the course of two years.

Human and environmental toll

Vladimirova has seen first-hand the psychological and commercial mechanisms that drive the global fast-fashion industry. Middle-class women especially tend to accumulate cheap, low-quality garments, most of which are produced abroad under precarious working conditions. April 24 marked the 10th anniversary of the tragedy at Rana Plaza, a building on the outskirts of Dhaka, Bangladesh, whose collapse killed 1,134 textile workers in 2013. The event brought global attention to the human exploitation behind the fast-fashion industry.

That industry also harms the environment, and the global figures are mind-boggling: fashion production is the second largest consumer of water in the world and is responsible for 20% of industrial wastewater from textile treatment and dyeing. After the garments are sold, they continue to pollute water. During washing, microfibres from synthetic materials like polyester, together with toxic chemicals, end up in waterways where they can be ingested by living creatures.

Buy, wear, throw away, repeat

Vladimirova’s research shows that cities like Geneva function as “pumps”, feeding garments into a second-hand market. Unwanted clothes and shoes end up in donation bags or are collected by companies that export them for recycling. Swiss consumers, the second richest in the world by GDP per capita, are well entrenched in this circuit. In 2022 Switzerland imported about 22 kilograms of textiles per person, more than 95% of all clothes bought in the country, and exported about 14 kilograms (used and new), according to the Federal Office for Customs and Border Security (FOCBS).

In Geneva, a centre managed jointly by the charities Caritas and the Centre Social Protestant sends 35% of donated clothes that are in poor condition to the recycling company Texaid, which exports them primarily to African and Asian countriesExternal link. Once there, according to Vladimirova, used textiles coming from Europe often end up in landfills because the quantity is too large and the quality too poor. Texaid told SWI swissinfo.ch by email that although the garments are only exported to licenced dealers, the company has no influence on how the clothes are disposed of in the destination country.

Recycling and re-thinking fashion

The reality is that less than 0.5% of discarded textiles are recycledExternal link into fibres today. This is because most garments are composed of textile blends for price reasons, making separation and re-use very complex and labour-intensive.

Europe is under growing political pressure to solve this. In March 2022, the European Commission published a proposalExternal link for a regulation that would make sustainable products the norm in the European Union. But crucial to this would be funding for research into the production of re-used materials and the reduction of petroleum-based and non-recyclable raw materials such as polyester. “We need to understand how we can use fibres in a way that we can recycle them and make them last longer,” says Françoise Adler of the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts. “And we can’t do that using today’s technologies and supply chains.”

Adler is another researcher who finds that studies of textile sustainability have been overlooked in Switzerland. It is frustrating to see how money is readily available for research in fields such as robotics and artificial intelligence, while we struggle to get national funds, she says.

The State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) and the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) have been supporting a programmeExternal link to promote more sustainable and transparent supply chains in the textile sector since 2020, with funding of CHF325,000 until 2024. But it is aimed at industry and does not promote research.

Countries such as the United Kingdom and Nordic states are a step ahead of Switzerland when it comes to sustainable fashion research. Kate Fletcher, the most-cited British scholar in the field, says this is thanks to a close link between industry and academia. But she says this close collaboration stands in the way of research that is too critical of the economic growth logic that dominates and drives the industry.

“We don’t need new technologies or new fibres because no sustainable solution is found in shopping malls,” says Fletcher, arguing that it would be more sustainable to simply produce and buy less clothing. “But that’s a message no one wants to hear.”

Edited by Sabrina Weiss and Veronica De Vore

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.