Preimplantation diagnosis explained

When reproductive decisions and politics meet, the ethical arguments can quickly become complex and passionate – as they should in a direct democracy. But how can we understand the medical procedure at the heart of the issue?

On June 5, the Swiss will vote – for the second time within 12 months – on allowing embryos created via in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) to be tested for genetic or chromosomal abnormalities prior to their implantation in a woman’s uterus.

It’s an issue that has stirred up social, ethical, and emotional arguments across the Swiss political spectrum.

Proponents of preimplantation genetic testing argue that the practice could help couples who have known genetic disorders in their medical history avoid passing on these traits to their children.

But some opponents condemn denying those with inherited genetic disorders the right to life. Others are concerned about the possibility of creating embryos for the sole purpose of providing stem cells to treat an ill sibling, or about the slippery slope toward “designer babies”.

In June 2015, the Swiss voted in favour of amending article 119 of the Swiss constitution to allow for preimplantation genetic testing. This change created a framework within which preimplantation genetic tests might be possible, but did not provide guidelines for how it should be implemented.

However, opponents of the respective law – the Reproductive Medicine Act (RMA) – have forced another nationwide vote, set for June 5, 2016. If approved, the revised RMA will provide the guidelines needed to regulate preimplantation genetic tests in practice for couples who risk transmitting a “serious” genetic disorder to their offspring, or who cannot conceive naturally.

Today in Switzerland, if a couple wishes to do preimplantation genetic testing they must travel abroad, as most other European countries permit it in some form. Otherwise, they must wait until 12 weeks into a pregnancy to conduct an amniocentesis. No more than three IVF embryos can be produced at one time, and they must all be implanted into a woman’s uterus immediately – a practice that raises the probability of a high-risk multiple pregnancy.

If approved, changes to the RMA would include increasing the maximum number of embryos that can be produced in an IVF cycle to 12, and allowing IVF embryos to be stored via freezing rather than implanted all at once. Creating embryos specifically for harvesting stem cells or for gender selection unrelated to a genetic disorder would still be prohibited.

Diagnosis versus screening

When we talk about preimplantation genetic tests, we are really talking about two different procedures: preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and preimplantation genetic screening (PGS). The two are often confused, as they are very similar – in fact, the technology is essentially the same. The difference lies in the patient groups seeking treatment.

PGD is used when there is a known risk of transmitting a certain disorder from parent to offspring, and it has been an established medical technique for about 30 years. In countries where PGD is permitted, couples who could otherwise become pregnant naturally undergo IVF specifically to create an embryo outside the womb, so that it can be tested for a specific genetic disorder prior to implantation.

PGS is a newer, more controversial technique used to screen IVF embryos for an abnormal number of chromosomes, and not a specific genetic abnormality. A healthy embryo should have exactly 46 chromosomes; more or fewer often results in miscarriage. Trisomy 21 – also known as Down syndrome – is one condition that can be detected using PGS.

Since the 1990s, PGS has become more widespread because many women who choose to have a child via IVF do so because they are of advanced maternal age, or because they have already experienced miscarriage or other fertility problems. The goal is therefore to minimise the chances of this happening again by helping to select the ‘healthiest’ embryo, chromosomally-speaking.

“In my view, we are still waiting for the reports of randomised controlled trials to confirm if PGS results in an increase in delivery rates. But there are clinics now that offer PGS for every single embryo for every single patient,” says Joyce Harper, a professor of human genetics and embryology at University College London and Deputy Director of the UCL Centre for PGD.

If given the green light on June 5, the revised RMA would allow both PGD and PGS to be practiced in Switzerland.

The tests – and the costs

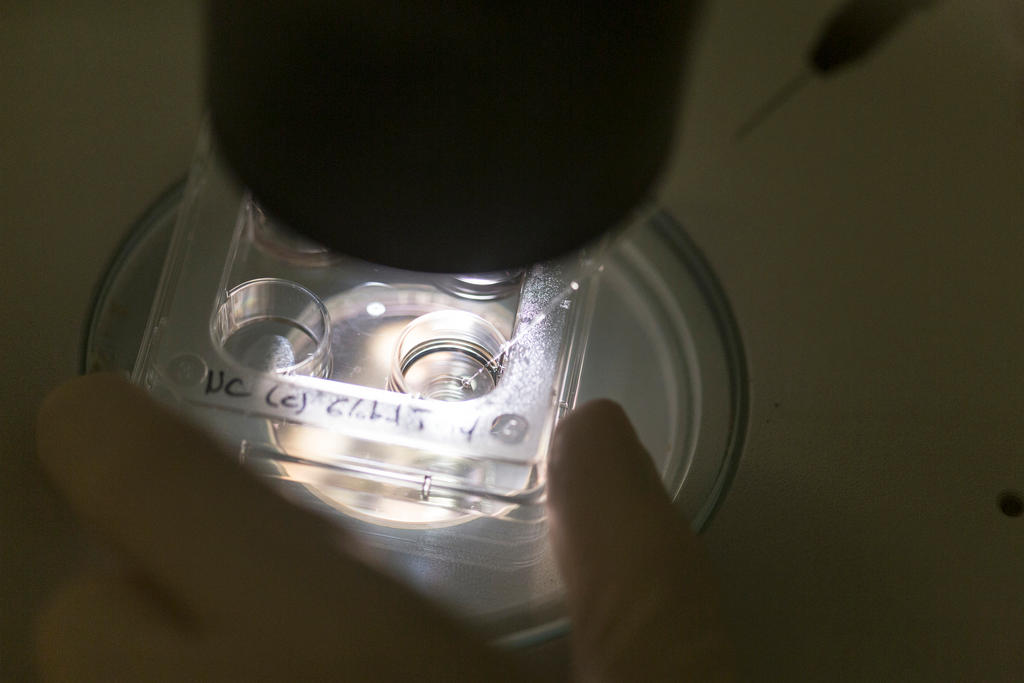

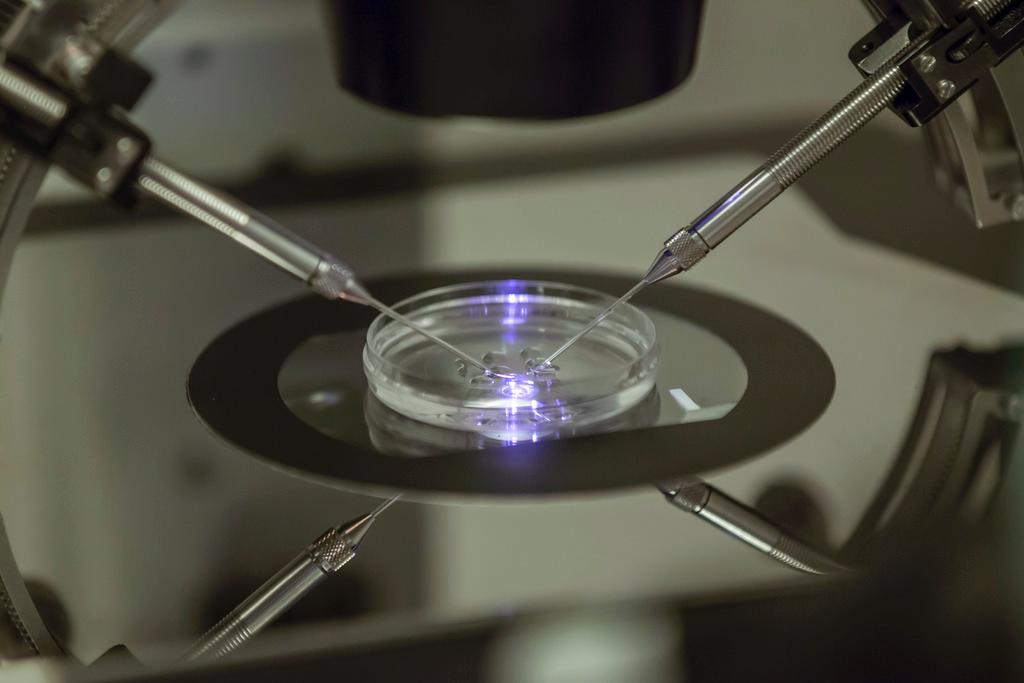

In the case of PGD, there are two stages to the procedure: the embryo biopsy, and the genetic testing.

The biopsy is most often done on the fifth day of embryonic development. In this procedure, doctors remove a few cells that will eventually become part of the placenta for testing. The inner cell mass, which will go on to develop into the foetus itself, is not biopsied.

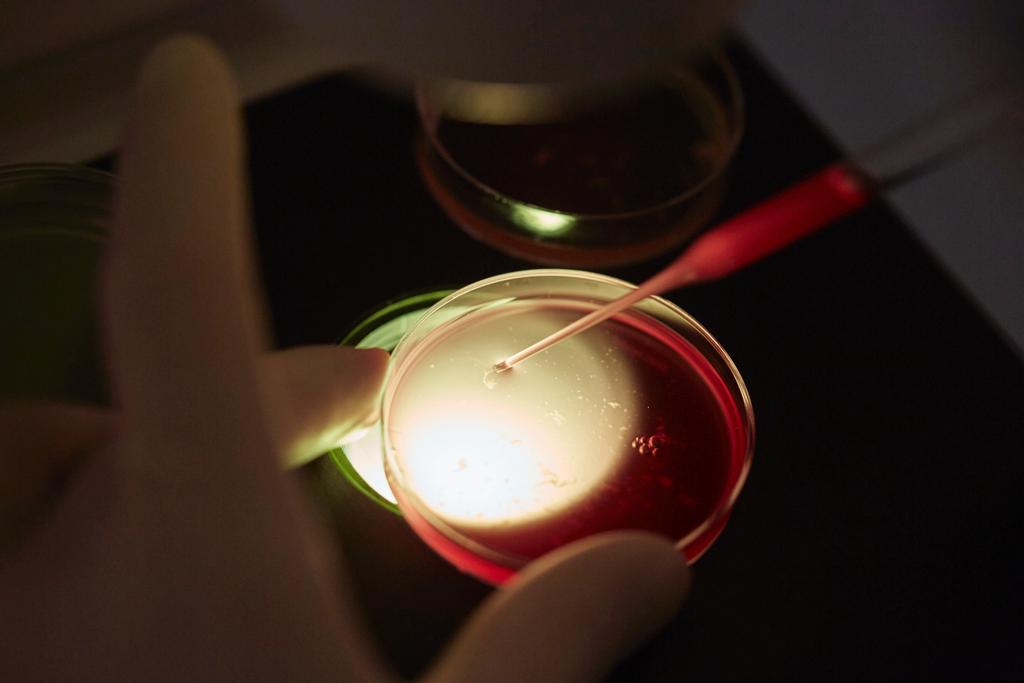

The biopsied cells are then sent to a laboratory for tests. There are hundreds of genetic conditionsExternal link that can be tested for using PGD, but the most common include cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs disease, spinal muscular atrophy, haemophilia, sickle-cell disease, Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, and thalassemia.

Medical costs vary widely, but Harper estimates that the average cost of PGD alone – not including IVF costs – is somewhere around €2,500 (CHF2,735). However in Switzerland, estimates range as high as CHF5,000-15,000. Swiss compulsory health insurance does not cover PGD or IVF, although it may reimburse patients for IVF-related hormone stimulation using certain drugs.

The biopsy and testing can technically be done within a day, although it is usually more efficient and cost-effective to perform tests in batches, leading to a longer overall waiting time of up to a month. In the interim, the embryos must be preserved, which is why the change to Switzerland’s RMA to allow embryo freezing would be an essential step toward permitting PGD in practice.

Although the basic procedure can be explained in just a few sentences, PGD is a difficult process because it requires otherwise fertile couples to undergo hormone therapy and egg harvesting as part of the prerequisite IVF.

“PGD is a very difficult procedure for a patient to go through, I feel – it’s not something a couple is going to go through lightly”, says Harper.

“If a couple chooses prenatal diagnosis, they get pregnant the old fashioned way, and then have a ten-minute procedure to do an amniocentesis…with the hope that everything is OK. But the problem with a prenatal diagnosis is that if the foetus is affected [by a genetic abnormality], the outcome of that would be a lot more traumatic because then they would have to decide to continue or have a termination.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.