What’s behind Switzerland’s star-studded Nobel success?

It’s not every day that astronomers and distant planets are splashed across every Swiss frontpage. But it’s not every day that Switzerland wins a Nobel Prize. That said, Switzerland has one of the highest Nobel-per capita ratios in the world. Why?

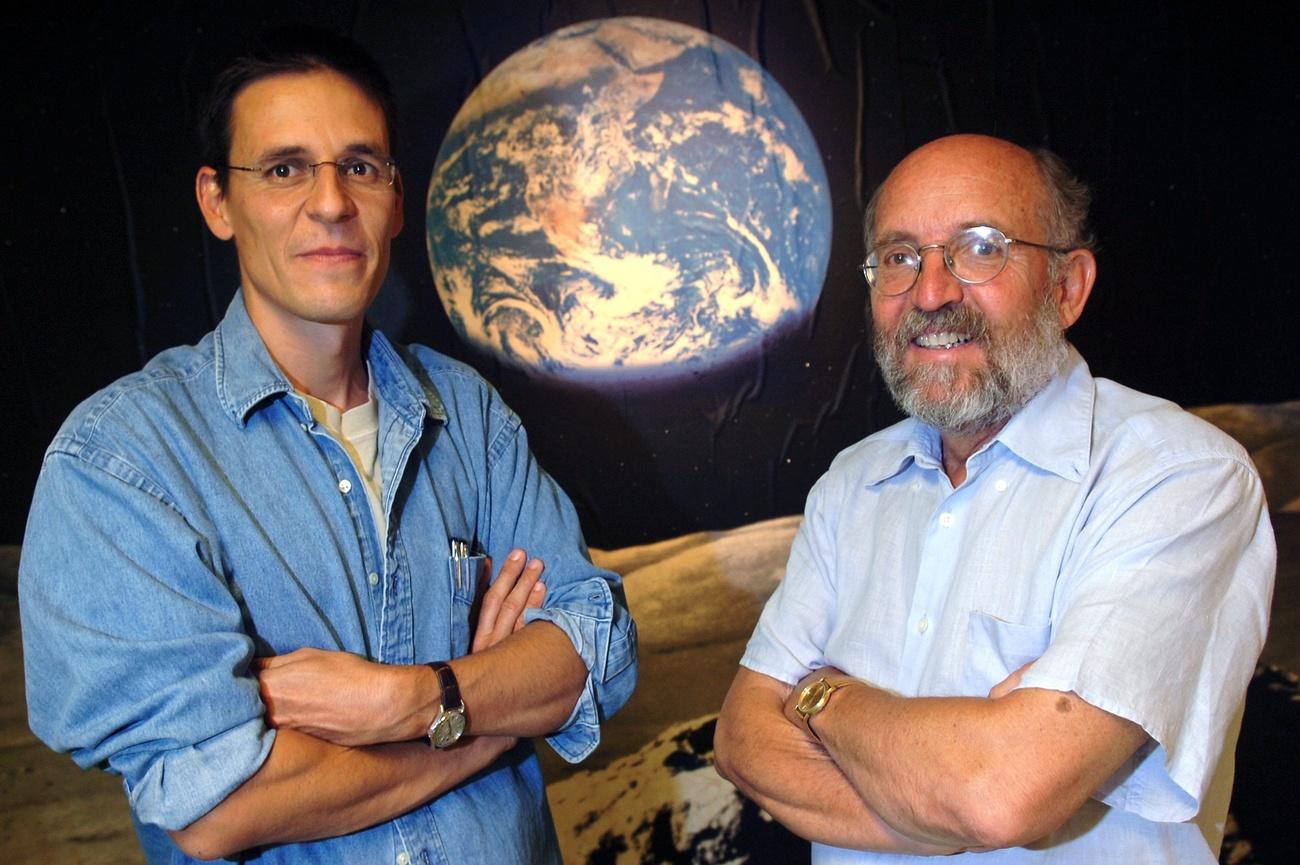

“Our Nobel stars”, “Geneva has its head in the stars” “French-speaking Switzerland, a Nobel breeding ground” – Swiss newspapers didn’t hold back on Thursday, the day after Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz from the University of Geneva shared the 2019 Nobel Prize for Physics for “the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting a solar-type star”.

Since Henry Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross, got the Swiss Nobel ball rolling in 1901 when he won the Peace Prize, a total of 30 awardsExternal link have gone to Swiss individuals. This puts Switzerland near the top of the list of Nobel laureates per capitaExternal link.

Hot phases include 1945-1957 (nine prizes) and 1986-1996 (five prizes). The prize for physiology or medicine has gone to a Swiss nine times, followed by chemistry and physics (eight each), peace (three) and literature (two).

These figures do not include the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences or the many Geneva-based organisationsExternal link, such as the IPCC or UNHCR, that have won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Swiss winners?

But what exactly is a “Swiss Nobel Prize winner”? Someone who lives and works in Switzerland or was merely born here? Is it a question of Swiss citizenship?

What about those winners who have a Swiss passport but have never set foot in Switzerland? And then there are those top brains who settled in Switzerland not altogether voluntarily – often during times of war – and took Swiss citizenship (or maybe not).

Take Paul Dirac, who shared the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics with Erwin Schrödinger. Dirac was born and bred in Britain, but because his father was an immigrant from canton Valais, Paul Dirac also had Swiss citizenship.

Then there’s Dirac’s Austrian-born colleague Wolfgang Pauli, who didn’t become a citizen of Zollikon in canton Zurich until after he had won his Nobel Prize in Physics in 1945. Pauli is included in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung’s list of 30 laureates; Dirac isn’t.

In addition, Nobels have been awarded to many foreign scientists who either studied in Switzerland or who taught at universities in Zurich, Geneva or Basel. Even more laureates cut their teeth at the many research institutes dotted around the country.

Coincidence?

In total more than 100 Nobel winners have a close connection to Switzerland. Is this just a coincidence?

Yes, says Werner Arber, an Aargau-born microbiologist and geneticist who shared the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. The cluster of prizes in Switzerland is “probably a statistical anomaly”, he told swissinfo.ch in 2009.

In the same article, Richard Ernst, a chemist from Winterthur who was awarded the 1991 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, said he was not so sure.

Ernst saw two reasons for the Nobel boom in Switzerland: first, the country sat on the fence during the two world wars and as a result attracted many of the best brains from across Europe.

Second, “the support and environment [in Switzerland] over the past 50 years has been extremely good. That doesn’t happen overnight – that’s the fruit of lengthy development”.

Good conditions

Ernst added that it had nothing to do with Switzerland being particularly intelligent. Rather, he said, “the good financial conditions draw excellent researchers from around the world, most recently from the United States”.

For this reason, Ernst said he was confident that Switzerland would be able to hold its position at the top of the Nobel charts. “The attraction for world-class people remains high – and I don’t see this changing.”

Indeed, Switzerland was recently named the only nation outside Britain and North America to make it into the top 20 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2020. The federal technology institute ETH Zurich came joint 13th.

Ernst admitted, however, that a Nobel Prize is not the only sign of outstanding research.

“Many scientists go away empty-handed despite deserving the top accolade,” he said. “Politics and a lot of luck often play a role.”

More

Zurich, a magnet for Nobel winners

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.