Can artificial intelligence and democracy co-exist?

Some people see artificial intelligence as a danger to democracy; others see it as a huge opportunity. Researchers and experts explain how algorithms and big data are deployed in Switzerland – and how they aren’t.

Voting in Switzerland takes place every three months. Fierce debates take place before the referendums, and the tone can be particularly aggressive online. Insults, pure hate and even murder threats are not unusual. This is a risk to democracy, says Sophie Achermann, the director of Alliance F, the largest umbrella group representing women in Switzerland.

“It is important to conduct tough but fact-based discussions,” Achermann says. “But hate on the internet impedes a diversity of opinions. People are scared of hate mail and prefer not to say anything.” Before the vote on the pesticide and drinking water initiative in 2021, for example, some politicians received so many hate mails that they didn’t want to appear in public, she says. That is not just a Swiss phenomenon: around the world, politicians are experience increasing hostility and threats online, especially womenExternal link and minorities.

Because of this, Alliance F developed an algorithm against hate speech. The algorithm is called “Bot DogExternal link”, because – like a dog – it sniffs out hate messages on social media and marks these posts. A group of volunteers then responds to each message. The idea is that hate in the internet should not go unchallenged and the discussion can be continued on a factual basis.

Bot Dog is still in the pilot stage. But its first attempts have been successful: researchers at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich und the University of Zurich followed the pilot project and discovered that responses calling for sympathy for those subjected to hate speech were particularly successful. Sentences such as “your post is very hurtful for Jews” resulted in the hate speaker either apologising or deleting the message.

In July, Bot Dog will make its official online debut. Anyone who wishes can take part in the project, Achermann says. Either by evaluating comments and helping the machine-learning algorithm to identify more accurately which comments contain hate speech, or by responding to the posts marked as hate speech.

More

Is artificial intelligence really as intelligent as we think?

Cooperation between algorithms and people

The Bot Dog is just one example of how artificial intelligence (AI) can strengthen democracy. Dirk Helbing, a professor of computational social sciences at ETH Zurich, sees immense potential in a digital democracy. He says he is considering a participative budget, where citizens can together determine how the budget of their town or community should be spent.

In the Zurich district of Wipkingen, this idea is already being tested. Using a digital platform, residents have decided in favour of city parks, a skate park and a street-food festival. Each of these projects is supported with CHF40,000 ($40,250) of taxpayers’ money.

Another idea for digital democracy is that cities and regions around the world could link up to take part in competitions for sustainable economies, CO2 reduction or peaceful co-existence – a kind of city Olympics. The solutions and related data would be open source, so freely accessible to everyone, and could serve as the basis for AI models. “I think we are heading towards a kind of digital participatory society,” Helbing says – a cooperation between AI and people, as is the case with Bot Dog, where an algorithm and volunteers combine forces to combat online hate.

AI has enormous potential for direct democracy, he says. But applications driven purely by data “also have enormous destructive potential for democratic societies based on the rule of law and human rights,” Helbing says.

More

Looking ahead to government by smartphone

Not all good

Algorithms are increasingly determining what information we receive, what products we are shown, and at what price. They determine what we see of the world and what problems we view as important. This is increasingly steering our political thinking and our voting behaviour, Helbing says.

That was manifest in Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential election campaign, for which his team used big data algorithms to create personalised content for his target groups. “We bombarded them with blogs, websites, articles, videos, ads until they saw the world the way we wanted them to. Until they voted for our candidate,” is how Brittany Kaiser described her campaign work in the Netflix documentary “The Great Hack.” Kaiser worked for Cambridge Analytica, the company that trawled the private data of 87 million Facebook profiles before the U.S. presidential election, sparking one of the biggest data scandals to date.

Even during Barack Obama’s second presidential campaign in 2012, voters were targeted with messaging. Obama’s team collected as much data as possible and sent each voter a personalised message.

It is impossible to state with certainty the extent to which AI campaign methods contributed to the success of the candidates. But Helbing and his colleagues see great danger in these methods. Above all, the combination of microtargeting and nudging with big data about our behaviour, feelings and interests could give rise to totalitarian power, Helbing says. Nudging is a psychological term and means prodding people for a specific purpose or in a particular direction.

AI voting campaigns in Switzerland

AI needs one thing above all else: data. And the more it has, the better it works. In Switzerland, data protection and privacy are highly valued. Would campaign methods such as those used in the US be possible here? Could Swiss parties get their message to voters using so-called microtargeting?

Lucas Leemann, whose work at the University of Zurich includes research into how public opinion can be measured with the help of machine learning, doesn’t believe this will happen.

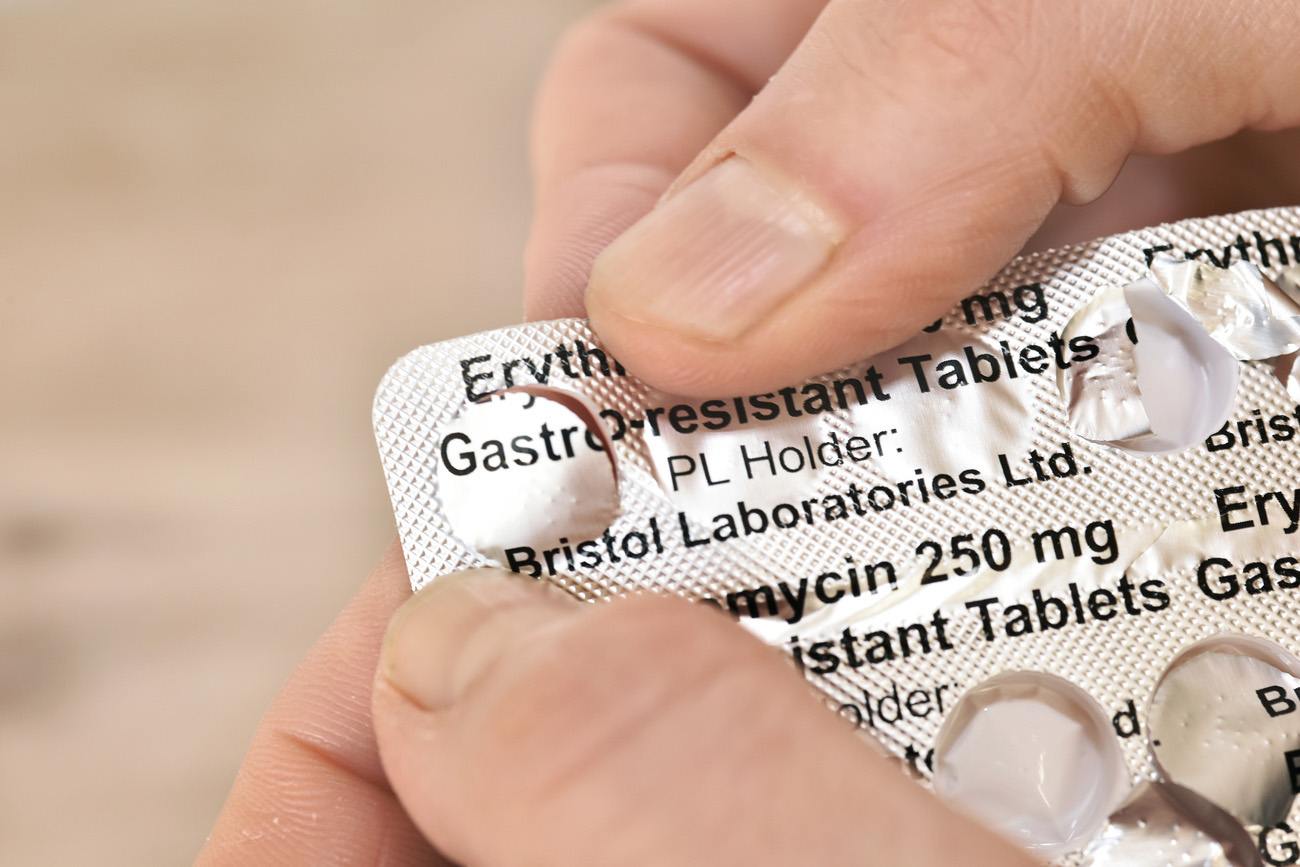

He says the situation in Switzerland is not comparable with that of the US. That, he says, is partly because the kind of raw data that the Trump and Obama campaigns used is not available in Switzerland. “They had datapoints for almost every citizen in the US,” he says. “That is completely different in Switzerland.”

During his studies, Leemann briefly worked for a fashion company in the US and not only had access to the customer database – so name, address and date of birth – but could also see estimates for their annual income, how many children they had, what car they drove and whether they rented or owned their own home.

“In the US, you can easily buy this data and it is also used for political purposes,” he says. “In Switzerland, as far as I know, this kind of data is not used for political campaigns, or at least, not yet.”

Is “not yet” the key? Will this data soon be for sale in Switzerland too? According to Helbing at ETH Zurich, data use worldwide is far more advanced than most people realise.

As an example, he names the World Economic Forum (WEF) Centre for Cybersecurity, headquartered in Geneva, in which organisations and companies from around the world participate – among them Amazon, MasterCard and Huawei Technologies. Helbing says “a huge amount of data is collected” there. The assembled data is used – with the blessing of the United Nations – for purposes including the implementation of Agenda 2030 for sustainable development.

“This may be well-intentioned but it gives rise to the question of how this is implemented and what else might be possible with all this data,” Helbing says. “As so many companies are involved, there is a danger that commercial interests could outweigh the social interests.”

More transparency

Experts warn that laws and regulations need to be created now to prevent AI from becoming a danger to democracy.

But in order to create functioning rules, it is necessary to know how exactly algorithms work. This is a problem. Platforms such as Facebook are a black box, says Anna Mätzener, the director of AlgorithmWatch Schweiz. “We don’t know, in detail, how the algorithms work,” she says. “We also don’t know exactly what data is collected about whom.”

AI that curates content on social media is a well-kept secret. To find out how algorithms affected election campaigns, AlgorithmWatch began a research projectExternal link in cooperation with the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper. They called on hundreds of volunteers to donate data from their Instagram timelines before the German election in 2021. The volunteers were asked to subscribe to the profiles of various parties. A browser-plug-in registered where and when the content of these profiles appeared in the newsfeeds of users and transferred this information to AlgorithmWatch.

The analysis showed that content from the radical right-wing AfD (Alternative for Germany) landed higher up in the Instagram newsfeed than those of other parties. The research could not pinpoint why that is the case.

For Meta (formerly Facebook), which owns Instagram, this research was clearly unpleasant: the company threatened AlgorithmWatch with “more formal steps” if the project wasn’t scrapped. As a result, the data donations ended prematurely.

“As long as this kind of research isn’t possible, we can’t say anything fact-based about what influence AI-curated content on platforms has on society, in particular on political opinion-building, and as a result, directly on democracy,” Mätzener says.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.